Transformation Through Poetry: A Conversation with Roz Weaver

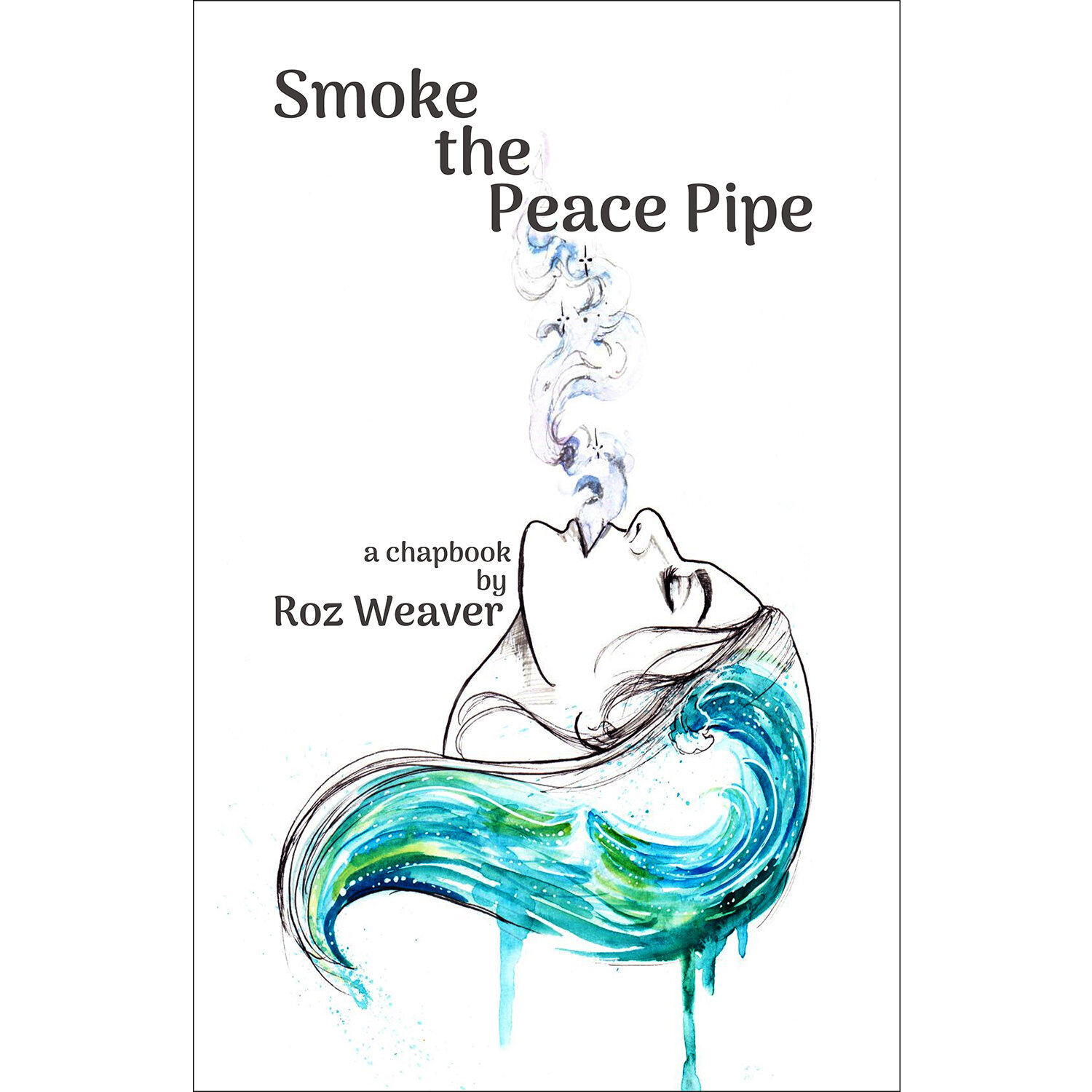

Roz Weaver is a poet and spoken-word artist who grew up by the beach in Fornby, near Liverpool, England. She now resides in Leeds where in addition to writing poetry she works as a social worker and is a licensed therapist. Weaver’s upcoming Yellow Arrow Publishing chapbook on trauma and transformation, Smoke the Peace Pipe, is now available for presale and will be released August 2020. Beginning Tuesday, July 21, Weaver will host a six-week “Poetry as Therapy” online workshop with Yellow Arrow.

Yellow Arrow editorial associate, Siobhan McKenna, spoke with Weaver about her new chapbook, spoken word, and her thoughts on using poetry as a therapy tool at a time when our world is in need of great healing.

YAP: How did you begin writing poetry?

I enjoyed drama as I was growing up and about three and a half years ago, I started writing and reading poetry. After I watched a TED Talk by Rupi Kaur, I read some of her poetry and started writing. I think some of the stuff that she talks about in her poetry is something that gave me the confidence to think about how I would word what I wanted to talk about. [My poetry] was all really terrible to start with, but then I went from there.

YAP: How did you start performing as a spoken-word artist?

Similar to how I started writing, I had in my head for about a year a piece that I thought would be really good as a spoken-word piece and there was a spoken-word night in Manchester and I put my name on the list, but I backed out a few days beforehand because I was terrified. It took about a year after that to try again, and I still have never performed that poem! But after that, I never started to specifically design my poems for spoken word, but I would go up on the stage more often. [Spoken word] still makes me feel anxious most of the time—I don’t really like it! But you have to keep putting yourself in that discomfort zone. I do get that buzz from performing, but all before it I’m a bunch of nerves!

YAP: What does spoken word bring to poetry?

I think it can bring something really different from page poetry. There are some great places around where I live that do spoken-word events and the poetry can blend to almost being like music or song—its lyrics, its rap, some of them have live bands that will improvise to the rhythm of how someone is speaking. And sometimes, there will be someone sitting in the audience who needs to hear what you’re talking about whether it’s a shared experience, a reframing of perspective, or they’re ignorant to the thing someone is talking about and they need to have that learning. There is also a community feel [during spoken-word performances] when everybody clicks their fingers when they agree with a bit in a poem—rather than clapping or whooping, which might interrupt the speaker—I find [the clicks] really cute and adds to the vibe.

YAP: How do you translate spoken to written?

When I am doing a spoken-word poem it takes me forever because I start it and then I try to find the next line and it will take me hours or days or weeks to put one together. And generally for spoken word, in order to speak long about a subject, I need to be pretty passionate about a subject that I can’t just summarize on a page.

YAP: Do you find different meanings coming through when performing spoken-word poetry that you didn’t realize when you originally wrote the piece?

[One poetry line] that I may think is a very significant line in a piece, someone else will jump to something completely different and say that was the bit that they really identified with, which is often similar to page poetry. Lines can be interpreted in really different ways and whether its spoken-word or page poetry, once [a poet has] written something we don’t have a say in what it means to other people. I really don’t like when someone introduces their piece and the introduction about their piece is as long as their piece. I think it prevents somebody in the audience from interpreting the piece in a different way and sometimes the way in which someone interprets your poem is better than what your original meaning was and you say [jokingly], “Oh, yeah, I totally meant that.”

YAP: How can poetry be used as a type of therapy?

Poetry is a form of expression, and I’ve found it’s easier to put things into words in a poem rather than speaking to somebody face-to-face. For example, sometimes in a conversation with someone they want to find a solution, and with a poem, you can leave it hanging with the raw emotion and you don’t have someone else giving you advice. Sometimes, you have the words for something, but you don’t know how to feel about it yet or you can be quite numb to something and it’s only after I wrote a poem that I’ve really connected what is going on for me.

YAP: What inspired you to create the “Poetry as Therapy” workshop [now sold out!] for YAP?

I’m in my final module of my creative writing masters and in my first year, we were asked to build a set of workshops. I have quite a lot of personal interest around therapy and poetry therapy because it is a bigger thing in America, but it doesn’t exist in the UK so I wanted to build on that idea. So I created the workshops for a university module and they were sitting there and I thought it would be nice at one point to do something with them. The original ones that I put together were for women who had experienced violence so for the Yellow Arrow sessions I adapted them.

YAP: Who should attend your workshops?

Anybody! I think if people are interested in poetry, creative writing in general, or if people are trying to work through things that are going on for them then it might be a good tool to start that journey. I am a qualified therapist but the workshops aren’t therapy. People don’t have to share anything that they don’t want to. A lot of [the workshop] will be [completing] different exercises and prior readings and going away and trying some of the [activities] out by yourself. I’m sure I’ll do all the exercises along with people—I probably need it right now as well!

YAP: Why were you drawn to publish with Yellow Arrow Publishing?

I love Yellow Arrow. It’s been two years since I was first published by [Yellow Arrow Publishing] in one of their journals. I’ve been published two or three times, and I’ve always found the process lovely. Gwen [the YAP founder] would handwrite thank-you notes and post me this hand-bound journal from America and it’s just lovely. I find it to be a very supportive environment, warm, welcoming, and I love that it promotes writers who identify as women. It feels like so much care is taken with people’s work. They care about you, and I really love the ethos of the organization.

YAP: The title of your chapbook, Smoke the Peace Pipe, sounds like a direct call to action and almost invites the reader to join with you as well, was this intentional and how did you settle on the title of the chapbook?

I wish that is why I chose that! I settled on it after I had already ordered the [poems in the] chapbook to flow from a place of challenge and dark to moving into the light and [“Smoke the Peace Pipe”] worked perfectly as the final poem. I was trying to think of titles, and I liked it as the overall theme of the book—finding peace with yourself. [Smoke the Peace Pipe] has that meaning with me.

Sometimes we are our own worst enemies, and we have all these different parts of ourselves, which we don’t let exist at the same time. We lock-off bits, we avoid things, and we don’t see how we can feel different feelings at once; we feel like we need to be on this linear trajectory. There’s a poet named, Ijeoma Umebinyuo and she has a poem that says sometimes, “Healing comes in waves / and maybe today / the wave hits the rocks / and that’s ok” and I wanted to get that across.

I suppose the peace pipe, in terms of symbolism as well, is a link to something spiritual, nature, mother earth, and to the things that can help heal us. The peace pipe as a symbol is something really sacred, and I wanted to honor where that comes from and not use the phrase lightly. I’m really aware that the meaning and the history are not mine. And I wanted to pay tribute to [the fact] that we learn from other communities and other ways of being, other ways of knowing.

YAP: How did you choose the cover art for the chapbook?

The cover [was] designed by a tattoo artist in Scotland, Joanne Baker. She was a fine arts grad before she got into tattooing. She did one of my tattoos that was in part inspired by Rupi Kaur. I love [Joanne’s] artwork and I wanted to do it with someone British and after thinking about how we could make it work, Joanne was up for it. I sent Joanne a few poems and she came back with a few different ideas and it worked like that. She’s just an amazing artist and she had never done a book cover before so for her it was something to add to the portfolio. It felt really good to collaborate with her rather than pick an image that didn’t have any meaning for me.

YAP: 2020 has been a turbulent year in many ways. What role does poetry play in the face of an ongoing pandemic and fervent call for action against racial injustice?

I think people have had a lot of alone time whether to read or write. And linking back to poetry as therapy, poetry is definitely a way to express frustrations, fears, or keep a record of the small daily things to be grateful for. I think for me I’ve seen more impactful poetry, not around coronavirus, but more around Black Lives Matter. I’ve seen a lot of spoken word that has shown up, and I hope that stays. There are a couple poets on Instagram who I follow with minority backgrounds and some of the work they share is so inspiring it just leaves me at a loss for words. I think poetry sparks debate and conversations. And I think that’s needed whether it is because people are feeling lonely or as a way to continue to inspire us and to think about and change how we do things and move to a new normal in terms of coronavirus or a new normal around Black Lives Matter or trans rights. And none of this is new; it was just buried. The other day I was listening to a poet in the UK, Benjamin Zephaniah. He is a spoken-word/music/performance poet and he wrote a song called, “Dis Policeman Keeps On Kicking Me to Death.” And he wrote that almost 10 years ago in relation to one of his family members who had a similar death to George Floyd, but in the UK. So one story just hits the news, but it’s been happening everywhere all the time, which is really scary.

YAP: Is there a limit to how poetry gives us access to someone else’s lived experiences?

I think someone has to be in a place to hear it, especially if it’s something that challenges their world views or something that could be triggering. At spoken-word events, some people will have trigger warnings before a piece. And it’s ok that we don’t get something that someone is talking about because it is beautiful that there are so many different perspectives—as long as it’s not harmful to somebody else.

YAP: What knowledge or feelings do you hope readers gain from reading your chapbook?

To put some context to it, the trauma I refer to is related to my experience with sexual violence. I didn’t want to expand loads because trauma can come in so many different ways for people, and I wanted it to be relatable to people who have been through anything. I hope that people can know that things get better. In terms of my healing, [it has been helpful] knowing that there are other people out there who get it and that you are not alone. If it reaches one other person and that makes them realize that someone has gone through something similar, survived, and is all right, then that is really important.

There is an article in The Independent that in the UK only 1.5% of rapists that are charged by police are prosecuted by the Crown Prosecution Service. I don’t know what world we are living in, but it’s not one that feels like it takes this stuff seriously. I think systems are failing so many people. And sometimes I read stuff like that and I think about all of the people who don’t report things to the police and why would they when that’s the statistic. And why would they when a lot of the police in the system treat women like they do—because it is majority women who experience [sexual violence]. For me, it is finding alternative ways for healing when you don’t always get the response that you want from the systems around you, from the people who you would want to get criminal justice from, and from people who are close to you who don’t know how to respond. [My chapbook] is something that can say that you are not alone and there are ways you can explore this and things that you can do to start to feel better.

*****

Every writer has a story to tell and every story is worth telling. Thank you Roz and Siobhan for such an insightful conversation. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.