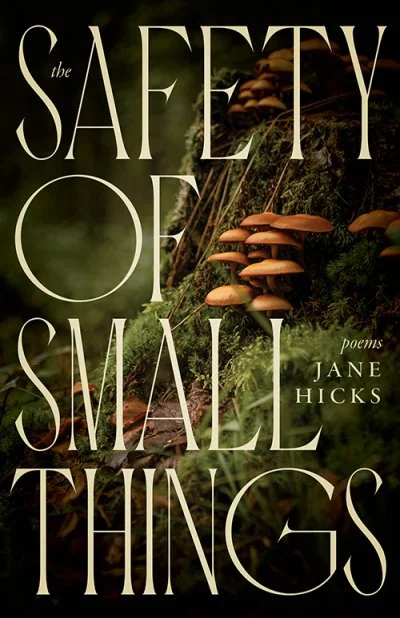

A Review of The Safety of Small Things by Jane Hicks

By Kellie D. Brown, written April 2024

“Open to air and sky, one feels none other / than small, a particle, a part, a leaf, a blade of a great whole”

In a world that seems to value bigger and grander, The Safety of Small Things, the third collection by award-winning Appalachian poet Jane Hicks, offers a counterpoint that speaks to the beauty and the necessity of the small and quotidian—“scraps, pieces, remnants of / a saving life” that help us inhabit the present and renegotiate with the past.

In Blood & Bone Remember (2008), Jane examined the generations who impacted her and the Appalachian region through their quilts, biscuits, music, coal mines, and sacrifice. In Driving with the Dead (2014), she beckoned readers to her beloved Appalachia to celebrate its tenacity and grace, and also to lament the suffering of its land and people. And now, Jane provides us with 51 poems that revisit the delights and trials of the distant past, and tackle her more recent journey of breast cancer, from the diagnostic phase to treatment and its aftermath. Throughout the collection, Jane traverses the complications of family and our own mortality, all the while reminding us to look to the natural world, where we can find strength and refugia. She is uniquely attuned to nature and how it can create a conduit for the voices of spirits from bygone eras—“I hear them speak in leaf-language.”

To those familiar with her, Jane is the “cosmic possum,” a term she coined in a 1998 poem (“How We Became Cosmic Possums”) that symbolizes the liminal space of her generation of educated folks, newly emerged from their mountain communities, who were often misunderstood and forced to bear the brunt of hillbilly jokes. “First generation out of the holler / . . . Neither feedsack nor cashmere / . . . Caught between Country Club and 4-H.” But rather than a limiter, Jane considers her experience of inhabiting both these worlds as an advantage, and she never apologizes for braiding the old mountain ways into modern life.

The bridge Jane uses to cross seamlessly from past to present and ridge to burg is her lifelong love affair with words, her “companions and confidantes.” In the epigraph to this collection, Jane quotes William Butler Yeats—“The world is full of magic things, patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper.” And indeed, this poetry collection issues a call to open our eyes, to perk up our ears, to let tingles run up our arms. She is particularly skilled in curating word sounds that luxuriate in melody and cadence—“rain-glazed,” “rusted reprimand,” “sun-dappled drowsy.” Our senses grow heightened to hear “the skitter of leaf-fall” and the “whir of hummingbird wing,” to feel the “sharp and flinty cold” and the “dew-wet meadow,” and to glimpse “dogwoods rusted at woods’ edge” and “the bob of flower heads as bees lift away.”

Alongside her depictions of nature’s simple extravagance, Jane refuses to shy away from the vulnerability of sickness and loss. In “Agent of Providence” and “The Unseen,” she revisits the extended illness of her mother whose “IV tubes arc out and glitter” in places where “hallways stir with the clatter of carts.” In “Spotlight,” she offers up her own diagnosis weighted by a “gel-sodden towel” after a damning ultrasound. She reminds us that we don’t emerge from the traumatic unscathed. Even as we become whole, “an undertow that lurks beneath/predictable waves” can still sweep us under.

She also pulls back the curtain of a painful childhood. A photograph from her fourth birthday in 1956 already reveals a wearier and more worldly wise girl than her age should bear (12–13). She has already learned the difficult lessons that “the dark shows truth” and that “hate hides / its face in unexpected places.” In school, she rehearses the duck and cover exercises of her Cold War youth, as she realizes that not all daddies are like her father, that some “hugged and kissed children, / helped with homework” and “that a daddy / most often was a good thing / and I learned to be sad.”

In addition to telling us what she has learned, Jane draws on her life’s work as a teacher to make this collection a series of lessons for the reader. She instructs us about the science of solar eclipses (“Safe Route”) and constellations (“Night Music”), and the theories of Galileo and Einstein (“Shine”). More importantly, she speaks about a point “where science and soul meet.” She describes a radiation treatment that coincides with the “moon-bitten sun” of a solar eclipse, and how she stands outside with staff and other patients to watch “the sunbeam crescent shadows.” In “Ode on an Onion,” her connection with the soul of science revisits the ridge of her childhood through her beloved granny who knew the secrets of an onion with its “layer by layer” and “golden skin”—a “poultice for a rattling chest” and fried with potatoes it “staved off hunger.” The onion—ordinary and yet “a miracle.”

As with the onion, Jane examines commonplace household items—twine, hoe, fabric, beeswax; and the ordinary of nature—leaf, deer, moon, moss, feather. She writes about artifacts from the women in her family that she cherishes and continues to use. She longs “to touch things my women touched” (Kept Things), even as she acknowledges the blessed release from materiality that comes with death—her grandmother’s objects became “things she no longer need carry.” These words about the paradox of seemingly unremarkable items of daily life resonate with those of the American writer and naturalist Henry Beston, who chronicled a year on his farm Maine in the 1930s. “When this twentieth century of ours became obsessed with a passion for mere size, what was lost sight of was the ancient wisdom that the emotions have their own standards of judgment and their own sense of scale. In the emotional world a small thing can touch the heart and the imagination every bit as much as something impressively gigantic.”

This act of elevating the small things often appears in her poems as dancing, both literal and metaphorical. In “Night Music,” Jane describes the thrill of being a hippie during the counterrevolution, when the soundtrack of Hendrix and Joplin and the exhilaration of dancing “sent us into crip autumn / sweat-soaked, long hair damp curtains” then inevitably grew tempered by “classmates called / to war.” Recalling a visit to her mother’s grave, “Dancing in the Stars” records a tribute as she “jitterbugged to the car” without “caring what an observer would think.” Then laden with chemotherapy’s needles, bruises, hair loss, and brain fog, the poet finds herself partnered in a “Dance with the Red Devil” that would ultimately be a “Dance for my life.”

“What is the importance of poetry in our world today?” To this question in a 2023 interview, Jane responded, “I always think of poetry as a shared experience. If the reader can say, ‘Hey, I feel that way, too!’ or ‘I never thought of it that way,’ life can be less complicated or frightening.” Perhaps this is truly the message of The Safety of Small Things, that our human journey, with its inherent triumphs and tribulations, can be easier if we open our eyes and hearts to the extravagant beauty of the ordinary and to each other. While we desire “a mirror that does not change / . . . a sunset that does / not bleed into the bruise of night,” Hicks helps us confront the inevitable evolution that brings illness and aging and loss, and she does so without grimness. Foregoing even a hint of the maudlin, she provides a hopeful lifeline to readers—“let go the hornets of worry, bathe in the stream of life.” “Expect gifts. / Shine!”

You can find The Safety of Small Things (2024) by Jane Hicks from the University of Kentucky Press at kentuckypress.com/9781950564378/the-safety-of-small-things.

Dr. Kellie D. Brown is a violinist, conductor, music educator, poet, and award-winning writer whose book, The Sound of Hope: Music as Solace, Resistance and Salvation during the Holocaust and World War II (McFarland Publishing, 2020), received one of the Choice Outstanding Academic Titles awards. Her words have appeared in Earth & Altar, Ekstasis, Psaltery & Lyre, Still, The Primer, Writerly, and others. More information about her and her writing can be found at kelliedbrown.com.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we AMPLIFY women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.