Writing Process Notes: How Not to Dread Revision

By Isabel Cristina Legarda, written October 2024

I often get a little flutter in my belly when I turn on my laptop to open a work in progress. Revision can be exciting, but also dreadful. I totally get the well-known quip (often attributed, probably erroneously, to Dorothy Parker), “I hate writing. I love having written.” It’s a joke, of course. I love writing. What I actually dislike is feeling unable to translate what’s in my mind faithfully onto the page. The many stops and starts of finding the right words, the right structure, or the right direction fill me with anxiety. I’ve put my forehead on a desk surface many times and whined, “C’mon, you can do it. Keep going.”

Shirley Jackson claimed she wrote her masterpiece “The Lottery” in one sitting. Her essay about the process, “Biography of a Story,” used to fill me with envy. It describes what I (and I suspect many others as well) fantasize about when envisioning the ideal writing process: sitting in front of a blank page, a lone figure is struck by a compelling idea which then gives rise to streams of just the right words, all written in one great, almost unstoppable torrent, bringing the mental vision to perfect fruition. Inspiration with a captial “I” makes the words flow as if beckoned by some unseen power, and the author sits there writing or typing furiously, barely able to keep up. Jackson’s first version of “The Lottery” may have flowed out with the kind of unusual ease writers dream of experiencing, but in reality, writing it still involved drafts, feedback, and revision, as the process does for most writers.

Though this much-desired writing flow does happen once in a while, I think it’s rare—certainly for me. I might be an especially slow writer. I dread what I’ll euphemistically call the shoddy first draft; I wince at how inadequate it looks and sounds, how embarrassing it is in the ways it misses the mark. I procrastinate to avoid reopening it and seeing all its blotches, blemishes, and giant pores.

The truth, however, is that revision is the heart of the writing process. It’s the space in which the chiseling and shaping of a block of words can set free the hidden, essential work (to borrow from Michelangelo). Craft takes good writing and turns it into art. Although the creative process can be mysterious and elusive, craft is technical enough to lend itself to a methodical approach.

When I’m revising a piece, any piece, I comb through it line by line and ask myself the same six questions:

1. Do I encounter glitches reading it out loud? (e.g., stumbling, awkward pauses, unpleasant sounds, and bad rhythm)

2. Do I need this word (or phrase)? (I’ll question articles and weak verbs like “to be,” adverbs, adjectives, and redundancies.)

3. Can I replace groups of words with fewer words or one word?

4. Is each word the best word?

5. Is the piece “saying” what I want it to? (What do I want it to say?) Can I apply Flannery O’Connor’s well-known quote about stories to it, i.e. is it “a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the [piece] to say what the meaning is?”

6. Does the piece contain a DYBI moment? (DYBI = draw-your-breath-in. Often in the form of a fresh image, insight, use of language, or surprising way of seeing something. Examples from the poetry world include “How to Prepare Your Husband for Dinner” by Rachelle Cruz, “Cult of the Deer Goddess” by Caylin Capra-Thomas, and “Epithalamion for the Long Dead” by Danielle Sellers.)

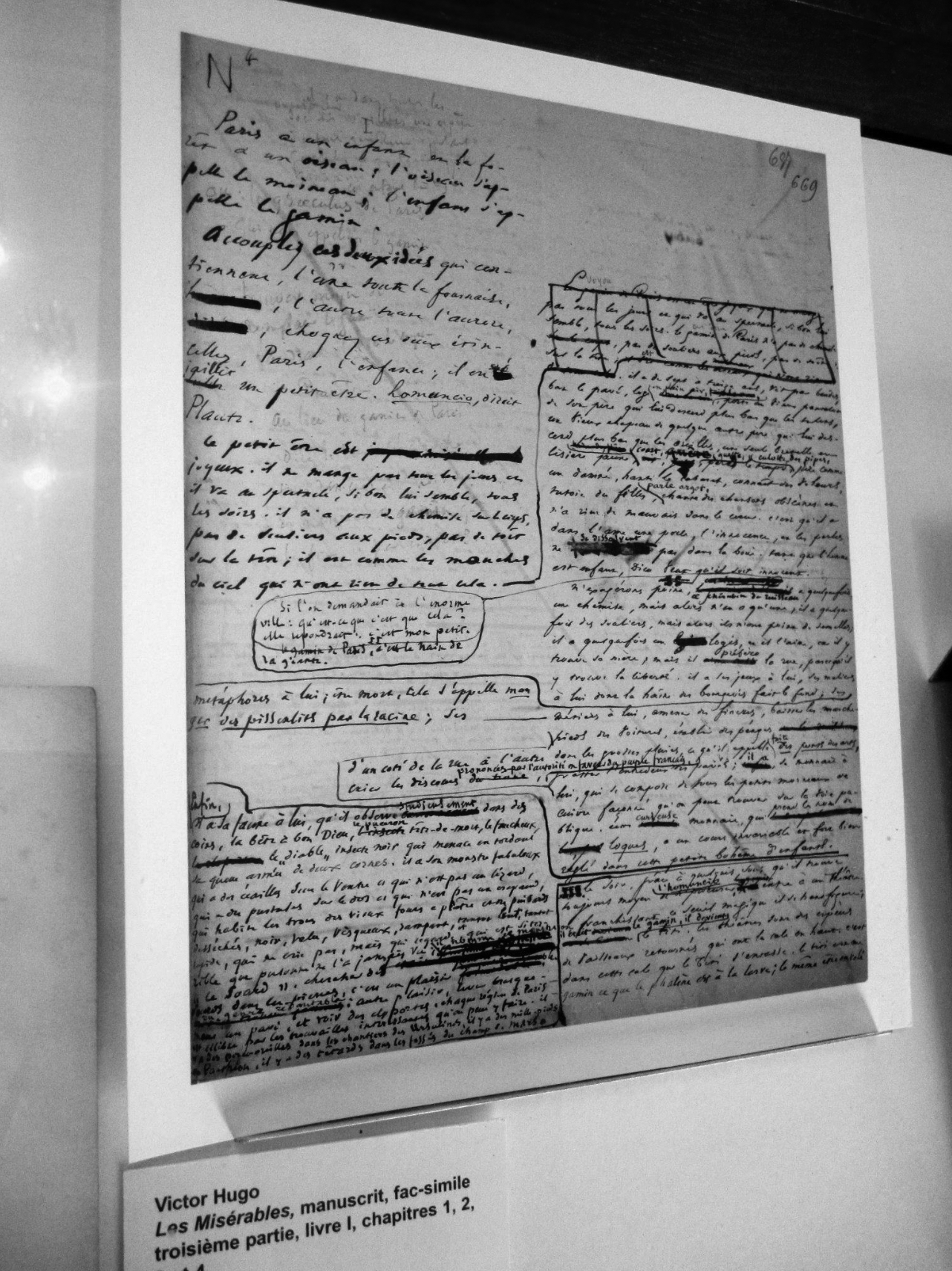

I take heart that even the greatest writers of the past have wrestled, Jacob-like, with the Angel of Revision, like Victor Hugo and Emily Dickinson, whose home in Amherst contains a large interactive display of lines from “A Chilly Peace infests the Grass” for which she trialed different words to see if they would work.

Interactive display at the Emily Dickinson Museum, Amherst, Massachusetts; photo by author

Facsimile of a page from Volume III, Book 1 of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, displayed at an exhibit of his drawings, Maison Hugo, Paris; photo by author

I enjoy catching glimpses of a writer’s process. Images of manuscript pages, with the authors’ crossings-out and scribblings, and literary journals like The Account, where writers explain the backstories of their works, and Underbelly, in which first and final drafts of each work are printed side by side, inspire me and fill me with curiosity and wonder. There’s a kind of flow evidenced in these too—the unfolding of increasing clarity as writers draw ever-closer to the voice and words they want. When I look at the opening lines of my own poem “Boondocks,” published in Beyond the Galleons (2024), in their very first and last iterations, I am startled by how different the two are, yet pleased that the soul of the poem inhabits both:

“Boondocks” ~ opening lines as published

I.

We hear the word and think

uncouth, naive, unsophisticated,

ramshackle huts off the grid,

prints of bare feet pressed

to dirt roads, scattered

corn husks, the smell

of burning wood, skin

prickling against the elements –

where a bad fall can mean

the end of life.

“Boondocks” ~ first draft of opening lines

If you’re from the boondocks

you might be stereotyped as uncouth,

naïve, unsophisticated, a fish

out of water in the civilized world.

We joke about the boonies –

how remote they are, how nothing

of any use can be found for miles,

just corn husks and the smell of wood

burning, ramshackle huts off the grid

along dirt roads carrying the prints

of the bare feet of unwashed, unschooled

children and the men who sired them,

who gather and cut firewood by hand.

Having crafted a piece for hours, days, or weeks, set it aside, revisited it, agonized, had the occasional break-through, and done as much as we think we can do, how do we know when a piece is “finished?” I don’t think we can ever be totally sure. Even the best writing samples could probably be tweaked or rewritten in a hundred more ways. I’ve had the experience of multiple voices offering feedback that led me to rework a piece many times, only to realize after some time away from the piece that my gut was still telling me the original “said it best” and later to have that very original accepted for publication. I’ve often wondered what would happen if I took a lesser-known work by a literary giant like John Donne or Virginia Woolf and distributed the piece without identification to a group of writers to workshop. I have no doubt there would be lots of eager critiquing. Someone always has a suggestion for even the greatest pieces of writing. At the same time, truly helpful feedback, from readers who understand and support the author’s vision, can elevate a work from good to great.

Flannery O’Connor wrote in The Habit of Being, “I am amenable to criticism but only within the sphere of what I am trying to do; I will not be persuaded to do otherwise.” I admire her strong faith in her own voice and work and strive to trust my own intention and vision for each piece that I write. In the end there’s nothing like applying a revision to a poem or short story, reading it to yourself, and exclaiming, “Yes!” in your heart. That feeling might even surpass the pleasure of writing that flows effortlessly onto the page by some “miracle” of Inspiration. With this in mind, I try to embrace revision. It is, after all, what makes us true writers, aspiring masters of our craft.

Isabel Cristina Legarda was born in the Philippines and spent her early childhood there before moving to Bethesda, Maryland. She holds degrees in literature and bioethics and is currently a practicing physician in Boston, Massachusetts. She enjoys writing about women’s lived experience, cultural issues, and finding grace in a challenging world. Her work has appeared in America Magazine, Cleaver, The Dewdrop, The Lowestoft Chronicle, Ruminate, Sky Island Review, Smartish Pace, Qu, West Trestle Review, and others. Find Isabel on Instagram and Twitter @poetintheOR.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.