Yellow Arrow Publishing Blog

Why I Love Poetry

By Caroline Kunz, written August 2024

In the words of Robert Frost, “Poetry is when an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found words.” A simple, yet meaningful phrase that largely sums up why I love poetry. Writing poetry allows one the space to grapple with and sort out their most complicated emotions and experiences. Reading poetry allows one the ability to find names for the feelings they once found too difficult to identify. In my experience, poetry brings with it the greatest sense of comfort and relief, no matter how one engages with it.

My sentiments toward poetry haven’t always been so fond. Growing up, I couldn’t stand it. English class was always my favorite—I loved sinking my teeth into books that made me think, like The Giver and To Kill a Mockingbird, and I aced every quiz on figurative language and literary terminology. However, something about the yearly poetry unit left me less than enthused. I thought that poetry’s primary purpose was to remain mysterious and inaccessible, hiding some deeper message that only those well-versed in literature could decode. I believed that all poems needed to sound like a nursery rhyme—the more elaborate the rhyme scheme, the better. Squinting at the board in the front of the room, I tried to piece together what Edgar Allen Poe’s Raven meant when it squawked, “Nevermore,” wondering what was so important about the repetitive word, anyway. I took a stab at analyzing “Jabberwocky” by Lewis Caroll but felt as though I was reading another language. Were “brillig” and “slithy” even real words?

It wasn’t until I studied poetry in my junior year of high school that my opinions started to shift. It’s true that one teacher can completely change a mindset, proving all preconceived notions about a subject to be false. On the first day of the unit, my English teacher had our class open our American Literature Anthologies to a piece called “Desert Places” by Robert Frost. My only experience with Frost at that point had been reading “Nothing Gold Can Stay” in S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders. All I remembered was how confused the short poem had made me feel. I didn’t expect to enjoy this next one, either. Nonetheless, we read.

“What do the images in this poem have in common?” My teacher asked. Everything is desolate and blank, I thought. “Beyond nature and the outdoors, what do these images make you think of?” Loneliness, isolation, melancholy. Maybe it was the step-by-step analysis that my teacher walked us through. Or maybe, it was the fact that at that point in my life, I’d learned the stresses of balancing school with a part-time job and extracurriculars, friendship drama, keeping a strong GPA, and applying to colleges. I’d experienced the nostalgia of growing older (perhaps, Frost was right, after all, when he concluded that “nothing gold can stay”), the sadness of losing a grandparent and an aunt, the uncomfortable presence of change. Maybe it was because I’d shared in these human experiences that I was able to put aside the rhyme scheme and see the poem for what it was: a testimony to the feelings of loneliness and uncertainty that all of us have experienced. An ode to the notion that, at times, we’ve all felt as though we’re wandering a barren path, isolated and alone in our fears that we’ll never find our way through the uncharted territory. It was beautiful. I felt a strange sense of comfort in reading these words—I didn’t know that poetry could be emotional and relatable, allowing readers to see their feelings represented and validated in such short stanzas. I copied the poem down into my notebook so I wouldn’t forget it.

From that point on, I became eager to find poems like “Desert Places”—poems that I could read and digest and apply so easily to my own life. I inhaled the works of Emily Dickinson and Wendy Cope, Oscar Wilde and Ralph Waldo Emerson. I was fascinated by the fact that older poems such as these could still hold so much weight, still resonate so deeply with readers of any age. Before I knew it, my bookshelf was overtaken by a collection of little poetry books.

It’s no surprise that once the poetry bug bit, I decided to study English and writing at college. At present, I’ve completed three years, and I can say with confidence that the poetry classes I take are my favorite. I love the poems that my professor brings for us to read each week—Elizabeth Bishop, Louise Glück, Robert Lowell. I love getting to explore new genres, forms, styles, and narrative voices. I love getting to know my classmates and their opinions so well as we bounce ideas across our classroom’s round conference table. I love our in-class workshops; before every Thursday, we each write a poem to be brought in and edited, questioned, admired, and reworked by our professor at the front of the room.

“No, you can’t use that cliche.”

“I admire the risks you took with this one.”

“Why don’t we just get rid of the first three stanzas?”

“The heart of the poem is really here, in the last two.”

I love the conversation that I have with her red pen as I make my edits the day after a workshop. It’s fascinating to create my own work, seeing which topics I gravitate toward and which I shy away from. While the essays and analyses that I’m assigned in my English classes often prove to be stressors, these poems that I have due each Thursday act as a release, both creatively and emotionally. And, in turn, I’ve found that crafting so many poems has helped to strengthen my writing in every other academic area—it’s helped me to find a sense of conciseness, a greater awareness of pace and phrasing.

Last spring, during the final week of my “Poetic Influence” class, my professor could see the weariness in our eyes. Our once lively class discussions had turned sullen and sparse. We begged for extensions and handed in late assignments left and right, which she usually had no tolerance for. With mere days before final exams began, we were giving her all that we had. “I thought today I’d bring in one of my favorites by Ellen Bass called, ‘The Thing Is,’” she said. “You all could clearly use it.”

In that moment, these words were exactly what I needed to hear. The stress and anxiety brought on by the upcoming exams, the 12-page paper I had due that night, my yearly end-of-semester mystery illness, the bittersweetness of saying goodbye to my friends for the summer, the fact that I hadn’t even begun to pack up my apartment for move-out . . . all seemed to melt away. Bass reminded me that pain, fear, and grief are all inevitable. Suddenly, my problems seemed to become a lot smaller, and I knew that, while I didn’t love life in this particular moment, I would soon “hold it like a face” and appreciate it once again.

So, if you ask me why I love poetry, the answer is simple. Poetry allows us to feel less alone. Poems are like companions. Little reminders that we can stick in our back pocket, taking them out and consulting their advice when we need it most. Poetry grows up with us; “Desert Places” is still with me, in that old notebook from junior year, and in the Frost books that I keep on my shelf. Poetry is more than mere pretty words strung together to sound like an ode or a fairy tale. Poetry is complex, emotive, withstanding. Poetry is universal.

Caroline Kunz (she/her) is a rising senior at Loyola University Maryland, where she studies English and writing on a pre-MAT track. She enjoys traveling, scouting out new coffee shops, and of course, reading and writing. As an aspiring educator, she hopes to share her love of the written word with future generations of students. Her current favorite authors include Taylor Jenkins Reid and Celeste Ng.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Reaching New Orbits with Feminist Speculative Writing by Angela Acosta

By Angela Acosta, written September 2024

The worlds of feminist speculative fiction and poetry are vast. They are filled with spacefaring humans creating homes on new planets, Earth dwellers seeking respite from the sun, ferocious river-born monsters, and high fantasy cities full of spells and runes. You may have read stories by Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia Butler, or CJ Cherryh that made you rethink what you thought you knew about science fiction, fantasy, and horror. Works by these writers offer alternate histories, examine human nature alongside aliens, and ask their readers tough questions. Feminist speculative fiction decenters whiteness and dismantles colonialism. It walks away from the Omelas to envision more just queer, trans, crip, Black, Indigenous, Latine, and Asian futures.

When I joined the Science Fiction & Fantasy Poetry Association (SFPA) in early 2022, I was in awe of the ecosystem of speculative poets, journals, and presses that awaited me. Since then, I have published my work in over 30 speculative literary magazines and worked with small presses to publish two Elgin nominated collections, Summoning Space Travelers (Hiraeth Publishing, 2022) and A Belief in Cosmic Dailiness (Red Ogre Review, 2023). Before then, I had only published a handful of nongenre poems and often got lost in the maze of poetry contests, vanity publishers, and beautiful literary magazines for which my work was simply not a good fit. I had read plenty of science fiction novels, YA dystopias, and literary classics, but I had yet to experience SciFaiku, experimental work, and narrative speculative poems.

I got my start as a speculative poet publishing “The Optics of Space Travel” in Eye to the Telescope. This piece, like much of my speculative writing, grapples with questions of cultural erasure, multilingualism, and family legacies:

My eyes are the bridge between worlds and generations,

when languages and cultures have been assimilated out of me.

I can still see the road ahead, of stories yet to be told,

onward towards Mars and the deceleration of the universe.

Feminist speculative literature is multilingual and multicultural, held steady with the promise that the cultures and languages of Earth will be spoken and celebrated in the future. As a child, I yearned to speak Spanish and to know the recipes and cultural traditions of my Mexican ancestors. Though I didn’t learn Spanish from my family, the language in all its linguistic diversity has become a part of who I am. I have grown from this cosmovisión, a worldview amplified by the many cultures where Spanish and indigenous languages of the Américas are spoken. The literature of Abya Yala, a Kuna word for the misnomer that is Latin America, is full of myths like El Dorado and La Malinche, fantastic journeys and lost homelands, and the recuperation of indigenous cultures and voices. For those who speak Spanish, I recommend Rodrigo Bastidas Pérez’s anthology El tercer mundo después del sol, a collection of stories from across Abya Yala that bring together techno futurism, folklore, horror, and many other speculative subgenres.

My science fiction poetry seeks to envision Latine characters thriving in worlds beyond Earth. I write in English and Spanish about a city built over the Chicxulub crater in “Paradise of the Abyss,” cook tamales with Martian cheese in “Tamales on Mars,” find a new home for the delightfully resilient axolotl in “Rewilding the Axolotl” (Star*Line vol. 47, no. 2), and celebrate a quinceañera (15th birthday celebration) en route to a new galaxy in “Andromeda’s First Quinceañera” (Space and Time issue 142). My bilingual collection A Belief in Cosmic Dailiness contains poems that envision the dailiness of human emotions and experiences in settings beyond Earth, from parties onboard a spaceship to creatures gathered around a campfire listening to filk music (sci-fi folk music). I wrote the collection to capture the wonder and possibility of Latine futures, even when our names and histories cannot be found on star charts.

Recent fiction by Valerie Valdes and Becky Chambers has shown me that space can be for every human and alien species. Their books depict a future where people of all backgrounds and abilities can make their way to crowded space stations and settle on exoplanets without destroying the local flora and fauna. Theirs is a future of accessibility and acceptance of ourselves and our pasts, a place full of found families, multispecies communities, and heartfelt laughter.

For those entering the world of speculative fiction, there are many journals accepting feminist work. The Sprawl Mag, edited by Mahaila Smith and Libby Graham, is a feminist speculative journal “focused on publishing perspectives that have historically been left out of canonical sci-fi and fantasy.” Radon Journal publishes antifascist and anarchist poetry and prose, including science fiction, transhumanism, and dystopia. Most importantly, these journals offer excellent feedback and support their contributors. Other venues for speculative work that I enjoy reading and writing for are Solarpunk Magazine, Heartlines Spec, If There’s Anyone Left, Utopia Science Fiction, and Shoreline of Infinity. Speculative writers of color should consider submitting to FIYAH (Black writers of the African diaspora) and Anathema (on hiatus, planning to return in 2025). For those with poetry manuscripts ready for submission, Interstellar Flight Press is a mainstay of the genre, Aqueduct Press publishes feminist science fiction, Prismatica is for LGBTQ+ writers, and I have personally enjoyed working with the editorial team at Red Ogre Review.

When I first watched the Diné science fiction short film “Sixth World,” written and directed by Nanobah Becker, I was excited to see Diné astronauts tackling the challenges of a mission to Mars. These feminist, anticolonial futures are not without the conflicts of present-day society but offer new perspectives on age-old challenges. Feminist speculative futures are not necessarily utopian, nor do they portray an amalgamation of existing human cultures. They are as specific to the cultures and peoples they depict as they are vast, always venturing for the journey through space and time to be inclusive and accessible.

Angela Acosta, PhD (she/her), is a bilingual Mexican American poet and Assistant Professor of Spanish at the University of South Carolina. She is a 2022 Dream Foundry Contest for Emerging Writers finalist, 2022 Somos en Escrito Extra-Fiction Contest honorable mention, and Utopia Award nominee. Her Rhysling nominated poetry has appeared in Heartlines Spec, Shoreline of Infinity, Apparition Lit, Radon Journal, and Space & Time. She is author of the Elgin nominated poetry collections Summoning Space Travelers (Hiraeth Publishing, 2022) and A Belief in Cosmic Dailiness (Red Ogre Review, 2023).

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Ecopoetry: The Web That Connects

By Laurel Maxwell, written December 2024

As humans we are part of an interconnected web just like the mycelium that snake underneath the soil. As writers we have found ways to write about this connection we feel to the earth, what makes us pause in delight. We know how to select the right words to write about a bee tumbling inside the lip of a poppy. Writing about nature has gone by different names over the course of history. Today we know it as ecopoetry, or ecopoetics. This form of poetry focuses on how humans interact with the world around them, the observations they make, and the natural world itself. It runs deeper than personifying a tree, it is seeing that tree surrounded by forest and wondering what the forest will look like in 10 or 20 years. Ecopoetry works as a way to understand and untangle our thoughts on how humans can harm something beautiful while simultaneously striving to protect it. It can also serve as a call to action to protect all that is already disappearing.

One of the first poems I fell in love with was Mary Oliver’s Spring Day. The iconic line “what will you do with your one wild and precious life” set something free in my soul. Since reading those words I have slowly gravitated toward poets who use nature to make sense of the world. Over time I found myself writing in the same vein. It wasn’t an intentional change, there was suddenly more to write about as climate catastrophe became front and center in my personal life. Months of extreme smoke kept me indoors during summer, and flooding disrupted daily life in the winter. But ecopoetry can also be a love poem. Writing about the way a hummingbird dips into a flower or a honeysuckle vine tangles in a chain-link fence. How nature is resilient in the face of its own destruction in the way humans are not. Years after a massive fire swept through a state park I returned to visit with my mom and husband. Yes, tree bark was blackened, but there were also tufts of green sprouting above our heads.

Ecopoetry isn’t a new form of poetry, think of those early contemporaries Henry David Thoreau and Walden. It does seem ecopoetry has taken on a sudden sense of urgency as the world tips and spins with an increase in natural disasters. It has heightened our awareness of being on this marble in the universe. In my quest to learn more I searched in the scraps of time before dinner, in a few silent morning moments for poets who were writing now. Isabella Zapatas’ Una Ballena es Un Pais (A Whale is a Country) showed me it was possible to write about ecological concerns in a way free of scientific jargon. I loved the creativity she used to discuss animals in their habitats and her perspective on the way humans interact with them. Wound Is the Origin of Wonder by Maya C. Popa was the second book that shook me awake to what writing to the natural world could look like. What made her work different was that she wrote from the lens of loss, to an environment that is all too quickly disappearing. Mary Oliver is the queen of writing toward what is outside our window from geese to grasshoppers. Maria Popava writes at the intersection of science, the environment and wonder. Rebecca Elson used her background in astronomy to write clearly crafted scientific prose while boldly coming to terms with her diagnosis of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Responsibility to Awe. Newer publications that give a nod toward women writers and the environment are Poetry in the Natural World edited by Ada Limon and Leaning Towards the Light, an anthology of poems geared toward gardeners. All these writers are playful and serious while grasping the fragility of humanity.

I didn’t see the turn in my own work toward ecopoetry until I submitted a series of poems for critique. The reader pointed out how often I returned to interweaving actions between humans and the environment. Within this larger theme I was also seeking to gather a sense of self. He gratefully pointed me toward writers who “document human interaction with the landscape.” I began to become aware of the poems I was drawn toward and found they all touched on nature with a hint of science to provide a sense of grounding. “Write about your obsessions,” Ellen Bass said in a workshop. I’m obsessed with this earth, its changing, and my place in it, the harm humans have caused. How destruction brings about beauty. And this is the root of ecopoetry: work that focuses on the natural world and how humans interact with the spaces they inhibit.

As writers we are often keen observers of the world. We don’t have the luxury of being Walden and spending years at a pond, but we can look outside the front door, at the spider web stranded between two porch beams, a flower sprouting in an unexpected location. This sense of observation lends itself to ecopoetry which places nature at the center rather than humanity. This written word helps to weave our existence within that of the natural world. How many times have I written about the waves in some sense? Their meditative fall and retreat? Or that waves always return to where they started. Smoothing eons of mountains to sand. One of the things I love about ecopoetry is that it can bring our world into focus with something as small as an ant; does the ant know the size of the leaf it carries across the foundation of the world? Or as large as the cosmos.

If you are interested in submitting, there are a variety of publications that are looking for pieces which focus on the natural world. These include Fly Away Literary Journal, Kelp, Tiny Seed, Canary, and Ecotone, among others. The website Poets for Science explores the connection between science and poetry. This well-curated site has ways to advocate for the environment as well as opportunities to share your own work.

In this world of uncertainty I know that I can write what I see as I walk to the store, as I move between classes where I teach. I have my favorite tree whose leaves alert me to the season’s changing well before the air cools. For me, when I write about the environment it helps to keep me rooted. It also helps me pay attention, which in turn provides me with more to sift through as I put words on the page. I hope that you, too, can find joy in the small moments of the natural world to keep yourself moving forever forward.

“What Needs Care”

By Laurel Maxwell

This warming cracked, catastrophically changed planet.

Even though it may be too late to reverse course.

Except right now there is a squirrel with a yellow nut in its jaws skimmering across the patio.

Buttercup blooms on the yarrow plant daring the sun to emerge.

On Thursday I swam out in the ocean.

Investigated a log surfing the currents.

Head in the murky wet I didn’t notice the seal patrolling close to shore.

Today Ruth brought a bounty of pears from her garden.

We handled them like treasures.

The once burned landscape is beginning to care for itself.

Regrowth slow, but there all the same.

The birds which are inhabiting the charred branches, hip high weeds marking the trail.

People tentatively stepping into a brighter landscape than the one they knew.

Who will care for the coral bleached of their colors?

The rising tide battering roads.

Floods that disappear whole towns.

Seeds whose DNA have been so altered whole plant species are disappearing.

What needs care are these bodies we forget

as we hurtle through time.

Their age insignificant as space dust on this

billion-year-old planet.

If interested in learning more about ecopoetry or writing your own, check out Writing Ecopoetry with Joanne Durham, which starts on March 5. In this workshop, participants will read and discuss poetry that spans a wide range of relationships between people and the rest of the natural world from anthologies such as Poet Laureate Ada Limon’s 2024 You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World, Camille Dungy’s Black Nature, and Bradfield, Furhman & Sheffield’s Cascadia Field Guide. Learn more about the class at yellowarrowpublishing.com/workshop-sign-up/p/writingecopoetry2025.

Laurel Maxwell is a poet from Santa Cruz, California, whose work is inspired by life’s mundane and the natural world. Her work has appeared at baseballballard.com, coffecontrails, phren-z, Verse-Virtual, Tulip Tree Review, and Yellow Arrow Vignette SPARK. Her creative fiction was a finalist for Women on Writing Flash Fiction Contest. Her piece “A Still Life” was nominated for Best of the Net by Yellow Arrow Publishing. She has a chapbook forthcoming from Finishing Line Press in 2025. When not writing, Laurel enjoys putting her feet in the sand, reading, traveling, and trying not to make too much of a mess baking in a too small kitchen. She works in education. You can find her at lgtanza.wixsite.com/writer or on social media @lomaxwell22.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Writing Process Notes: How Not to Dread Revision

By Isabel Cristina Legarda, written October 2024

I often get a little flutter in my belly when I turn on my laptop to open a work in progress. Revision can be exciting, but also dreadful. I totally get the well-known quip (often attributed, probably erroneously, to Dorothy Parker), “I hate writing. I love having written.” It’s a joke, of course. I love writing. What I actually dislike is feeling unable to translate what’s in my mind faithfully onto the page. The many stops and starts of finding the right words, the right structure, or the right direction fill me with anxiety. I’ve put my forehead on a desk surface many times and whined, “C’mon, you can do it. Keep going.”

Shirley Jackson claimed she wrote her masterpiece “The Lottery” in one sitting. Her essay about the process, “Biography of a Story,” used to fill me with envy. It describes what I (and I suspect many others as well) fantasize about when envisioning the ideal writing process: sitting in front of a blank page, a lone figure is struck by a compelling idea which then gives rise to streams of just the right words, all written in one great, almost unstoppable torrent, bringing the mental vision to perfect fruition. Inspiration with a captial “I” makes the words flow as if beckoned by some unseen power, and the author sits there writing or typing furiously, barely able to keep up. Jackson’s first version of “The Lottery” may have flowed out with the kind of unusual ease writers dream of experiencing, but in reality, writing it still involved drafts, feedback, and revision, as the process does for most writers.

Though this much-desired writing flow does happen once in a while, I think it’s rare—certainly for me. I might be an especially slow writer. I dread what I’ll euphemistically call the shoddy first draft; I wince at how inadequate it looks and sounds, how embarrassing it is in the ways it misses the mark. I procrastinate to avoid reopening it and seeing all its blotches, blemishes, and giant pores.

The truth, however, is that revision is the heart of the writing process. It’s the space in which the chiseling and shaping of a block of words can set free the hidden, essential work (to borrow from Michelangelo). Craft takes good writing and turns it into art. Although the creative process can be mysterious and elusive, craft is technical enough to lend itself to a methodical approach.

When I’m revising a piece, any piece, I comb through it line by line and ask myself the same six questions:

1. Do I encounter glitches reading it out loud? (e.g., stumbling, awkward pauses, unpleasant sounds, and bad rhythm)

2. Do I need this word (or phrase)? (I’ll question articles and weak verbs like “to be,” adverbs, adjectives, and redundancies.)

3. Can I replace groups of words with fewer words or one word?

4. Is each word the best word?

5. Is the piece “saying” what I want it to? (What do I want it to say?) Can I apply Flannery O’Connor’s well-known quote about stories to it, i.e. is it “a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the [piece] to say what the meaning is?”

6. Does the piece contain a DYBI moment? (DYBI = draw-your-breath-in. Often in the form of a fresh image, insight, use of language, or surprising way of seeing something. Examples from the poetry world include “How to Prepare Your Husband for Dinner” by Rachelle Cruz, “Cult of the Deer Goddess” by Caylin Capra-Thomas, and “Epithalamion for the Long Dead” by Danielle Sellers.)

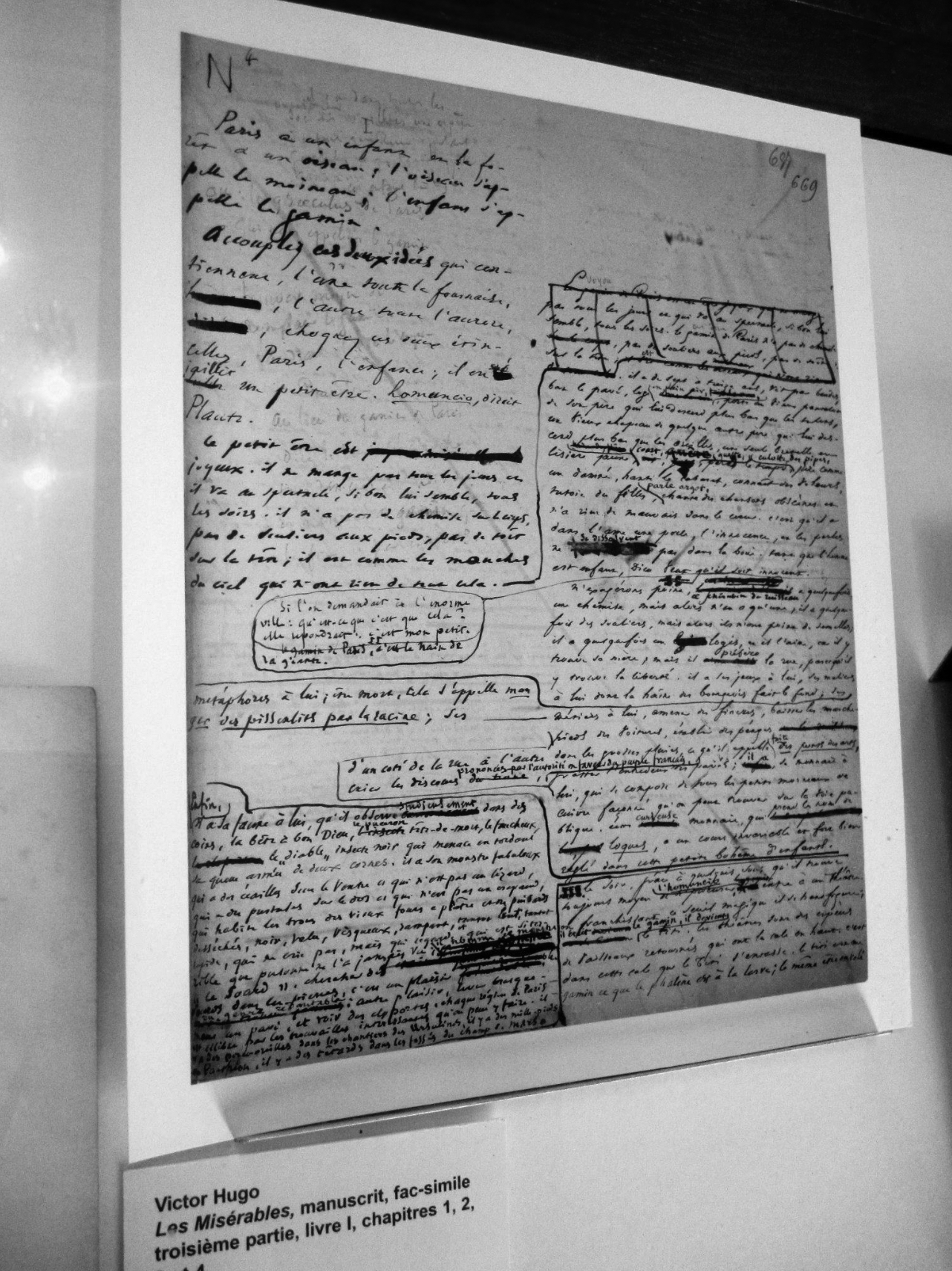

I take heart that even the greatest writers of the past have wrestled, Jacob-like, with the Angel of Revision, like Victor Hugo and Emily Dickinson, whose home in Amherst contains a large interactive display of lines from “A Chilly Peace infests the Grass” for which she trialed different words to see if they would work.

Interactive display at the Emily Dickinson Museum, Amherst, Massachusetts; photo by author

Facsimile of a page from Volume III, Book 1 of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, displayed at an exhibit of his drawings, Maison Hugo, Paris; photo by author

I enjoy catching glimpses of a writer’s process. Images of manuscript pages, with the authors’ crossings-out and scribblings, and literary journals like The Account, where writers explain the backstories of their works, and Underbelly, in which first and final drafts of each work are printed side by side, inspire me and fill me with curiosity and wonder. There’s a kind of flow evidenced in these too—the unfolding of increasing clarity as writers draw ever-closer to the voice and words they want. When I look at the opening lines of my own poem “Boondocks,” published in Beyond the Galleons (2024), in their very first and last iterations, I am startled by how different the two are, yet pleased that the soul of the poem inhabits both:

“Boondocks” ~ opening lines as published

I.

We hear the word and think

uncouth, naive, unsophisticated,

ramshackle huts off the grid,

prints of bare feet pressed

to dirt roads, scattered

corn husks, the smell

of burning wood, skin

prickling against the elements –

where a bad fall can mean

the end of life.

“Boondocks” ~ first draft of opening lines

If you’re from the boondocks

you might be stereotyped as uncouth,

naïve, unsophisticated, a fish

out of water in the civilized world.

We joke about the boonies –

how remote they are, how nothing

of any use can be found for miles,

just corn husks and the smell of wood

burning, ramshackle huts off the grid

along dirt roads carrying the prints

of the bare feet of unwashed, unschooled

children and the men who sired them,

who gather and cut firewood by hand.

Having crafted a piece for hours, days, or weeks, set it aside, revisited it, agonized, had the occasional break-through, and done as much as we think we can do, how do we know when a piece is “finished?” I don’t think we can ever be totally sure. Even the best writing samples could probably be tweaked or rewritten in a hundred more ways. I’ve had the experience of multiple voices offering feedback that led me to rework a piece many times, only to realize after some time away from the piece that my gut was still telling me the original “said it best” and later to have that very original accepted for publication. I’ve often wondered what would happen if I took a lesser-known work by a literary giant like John Donne or Virginia Woolf and distributed the piece without identification to a group of writers to workshop. I have no doubt there would be lots of eager critiquing. Someone always has a suggestion for even the greatest pieces of writing. At the same time, truly helpful feedback, from readers who understand and support the author’s vision, can elevate a work from good to great.

Flannery O’Connor wrote in The Habit of Being, “I am amenable to criticism but only within the sphere of what I am trying to do; I will not be persuaded to do otherwise.” I admire her strong faith in her own voice and work and strive to trust my own intention and vision for each piece that I write. In the end there’s nothing like applying a revision to a poem or short story, reading it to yourself, and exclaiming, “Yes!” in your heart. That feeling might even surpass the pleasure of writing that flows effortlessly onto the page by some “miracle” of Inspiration. With this in mind, I try to embrace revision. It is, after all, what makes us true writers, aspiring masters of our craft.

Isabel Cristina Legarda was born in the Philippines and spent her early childhood there before moving to Bethesda, Maryland. She holds degrees in literature and bioethics and is currently a practicing physician in Boston, Massachusetts. She enjoys writing about women’s lived experience, cultural issues, and finding grace in a challenging world. Her work has appeared in America Magazine, Cleaver, The Dewdrop, The Lowestoft Chronicle, Ruminate, Sky Island Review, Smartish Pace, Qu, West Trestle Review, and others. Find Isabel on Instagram and Twitter @poetintheOR.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Down to Every Word: A Conversation Across Genres with Jennifer Martinelli Eyre

For Jennifer Martinelli Eyre, life comes with many hats. She is a wife, a mother, an employee, a daughter, a sister, a niece, and a writer, residing in Harford County, Maryland. At the end of a long day, you might find her tucked away in a home office, scribbling her next work on a vibrant pink chair. Jennifer’s poem, “If Barbie Were My Daughter,” was featured in Yellow Arrow Journal ELEVATE (Vol. IX, No. 1). You can also find her poem, “Better” in Yellow Arrow Vignette AMPLIFY.

Elizabeth Ottenritter, Yellow Arrow Publishing’s fall 2024 publications intern, and Jennifer engaged in a conversation through email where they discussed the craft of free-verse poetry and writing realities across genres.

You have resided in Maryland your entire life—do you have any early memories rooted in Baltimore that may have influenced your interest in writing?

I have been a fan of musical theater since early childhood. I was, and continue to be, drawn to the power of lyrics and the stories they tell. Seeing as though I cannot sing or dance, my admiration for the performing arts often took place in the seat of many Baltimore theaters such as the Morris A. Mechanic Theatre, Lyric Baltimore, and Hippodrome Theatre. I have countless memories of sitting on the velvet edge of my seat, mesmerized by the words being sung from the stage. Having access to these performances fueled my love for words and played a large role in my obsession with storytelling.

How would you describe the writing scene in Baltimore? Have you found a network of fellow artists?

I am just beginning to dip my toe into the Baltimore writing scene. Through social media, I have discovered local treasures such as the Ivy Bookstore, and I’ve long admired the city’s devotion to independent booksellers. I recently attended my first Baltimore Book Festival and was overwhelmingly inspired by the city’s love and support of the literary arts. The amount of joy and inspiration in the air was infectious, and I honestly didn’t want the day to end.

Prior to Covid, I joined the local Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) chapter where I connected with fellow Maryland writers all in various points of their writing careers. The resources and comradery were unlike anything I’ve ever experienced, and I’m proud to say I’ve made some lifelong friends through the SCBWI. I highly recommend seeking out the SCBWI if you write (or illustrate) for children and young adults.

I would love to hear about your MFA experience and how writing for children/young adults has influenced your approach to writing.

Writing for children and young adults has taught me the importance of unique character perspective. For example, an adult character walking down dark, basement stairs may view their surroundings differently than a child walking down the same set of steps. An adult may view the darkness as nothing more than an annoyance because their spouse failed to change a lightbulb. A child on the other hand, may feel like they are venturing down a dark tunnel to a deadly dungeon. A story can go in multiple directions when you take the time to analyze a character’s perspective. It’s so easy to write from the perspective of where we are in life (adults) but to step into the shoes of a child truly changes everything. This is just one of hundreds of lessons I took with me from the program.

When you write a free verse poem, where do you begin? What tends to come to you first?

My approach to free-verse poetry is rather unstructured. I view free-verse poems as internal thoughts. For example, we don’t think in complete sentences. We don’t process information internally with proper grammar or rhyme schemes. Thoughts come to us as an immediate reaction to a given event, and it’s those unfiltered moments that typically spark my entry point into a free-verse poem. From that point on, I work to fine tune the message or theme while striving to keep the vulnerability and honesty of the poem’s message.

Give me Better Homes and Gardens

without the strands of pearls.

Show me the woman bundled in a blanket, her golden strands now gone.

A warrior on a hospital bed throne, pulling the weeds of cancer from her garden

with grace, poison, and prayer.

“Better” from Yellow Arrow Vignette AMPLIFY

Your poem “Better” is unique in its framing and repetition. Do you feel that the poems you write reflect a certain headspace you were in at the time? Or a physical place?

I have had moments in my life that I was only able to process through writing. I find that these poems tend to be more for me than for sharing. It’s a way for me to face the truth of what I’m experiencing which is not always easy.

Poems such as “Better” come from a space held a little more at arm’s length. The line, “Show me the woman bundled in a blanket, her golden strands now gone,” wasn’t written from a specific personal experience, but more from a collection of experiences watching people I love battle cancer at various points in my life. However, pulling bits and pieces from my past for a poem doesn’t always feel intentional. Sometimes the truth I weave into my poems is so quiet that I don’t even realize I’m pulling from experiences until the words settle on the page.

You mentioned weaving pieces of yourself alongside vulnerabilities in “If Barbie Were My Daughter.” How do you move past fear of exposure while crafting a candid piece such as this?

Poems such as “If Barbie Were My Daughter” do expose a part of myself that isn’t always easy to see. I’d be lying if I said that I’ve never been afraid to share personal experiences and vulnerabilities in my poems. The fear and discomfort typically boil over in the drafting/revising phase. Having your truth stare back at you from a page can be disarming, and it’s in those moments that I allow myself to experience the fear.

However, when the piece is complete and ready to share, I no longer view the work as something private I’m revealing about myself. Rather, I take a few steps back from the piece and create space for others to connect to the work in their own way. My poems are bigger than me, and it would be selfish to think I’m the only one on the planet who’s felt a particular way. My hope is that by sharing my vulnerabilities, I can inspire others to come to the table with their experiences. Fear feeds of off loneliness and wilts in a crowd.

How do you approach revising your own poetry?

I approach my revisions by first determining what it is that I want a poem to convey. I then look for areas where I said too much or said too little. It’s important to me that my words not only share a thought or experience (whether fiction or reality) but that they also leave room for the reader to find their own connection and interpretation. I will rework a poem endlessly until I feel that I’ve created a space for both on the page.

What types of art do you feel you respond to the most? How do they manifest in your own work?

I enjoy contemporary prose fiction, and my nightstand is currently stacked with such books. In free-verse poetry, there is an overwhelming call for brevity that doesn’t exist on the same level in prose. Every word in a poem must serve a precise purpose. That’s not to say that prose allows for needless detail, but it does add a layer of storytelling that inspires me. For example, I will get lost in a chapter that talks about nothing but the smell of a fresh cut grass from the perspective of a man who’s just been freed from prison. I want to know every detail of what that grass smells like to this character because it’s significant to who this person is and what they’ve been through.

After I finish a story written in prose, I will always take a moment and ask myself if that same story could have survived in a free-verse format. Sometimes the answer is yes and sometimes it is no. Regardless of the answer, it’s the process of asking myself these questions that helps me become a stronger, more intentional storyteller.

At the Baltimore Book festival, you told me to write what I wanted and to not let anyone tell me what I should write. I think this is such a powerful notion. Do you have any more advice for young women writers who are new to the publishing/literary world?

Women continue to be challenged by those too afraid to hear what we have to say. We are told to be quiet, comply, and to not talk about the hard things because it makes others uncomfortable. In my experience, being silenced and censored has only strengthened my literary voice.

My advice to women new to the publishing world is to go with your gut when it comes to your writing. Only you know what drove you to pick up that pen and place those words on paper; it’s crucial that you hold onto this. It can be quite easy to let the opinions of others dim the spark that started the whole project, but don’t let it. You have something to say, and the world needs to hear it.

Jennifer Martinelli Eyre graduated with her MFA in writing from the Vermont College of Fine Arts in January 2023, where she spent her time studying writing for children and young adults. Jennifer enjoys exploring various literary styles of writing, particularly free verse poetry. When she is not writing, Jennifer can be found behind a desk at her full-time job or reading one of the many books piled on her nightstand. Jennifer has resided in Maryland her entire life and currently lives in Harford County with her husband, daughter, and ornery cat. You can find her on Instagram and Thread at @jmeyrewriter.

Elizabeth Ottenritter (she/her) is a senior at Loyola University Maryland, where she studies writing. She is passionate about reading, crafting poetry, contributing to Loyola’s literary art magazine, Corridors, and traveling worldwide. Upon graduation, Elizabeth hopes to continue her love of learning and language in a graduate program.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Tips on Submitting Your Work to Literary Publications

By Leticia Priebe Rocha

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, I found myself (like many people) contemplating where my life was going after any semblance of a plan went out the proverbial window. I had an epiphany that I refer to as my Billy Crystal in When Harry Met Sally confession moment: “When you realize you want to spend the rest of your life with somebody, you want the rest of your life to start as soon as possible.” Except for me, instead of a stunning Meg Ryan as Sally, my beloved is poetry. I felt a great sense of urgency to share my work with others. I was also acutely aware of my inexperience—I’d been writing since high school, but I had virtually no exposure to the literary world and had no idea how any of it worked.

I vaguely remembered advice from a creative writing professor in college—typically people start their writing careers by submitting their work to literary magazines. I Googled around and eventually found some open submission opportunities. My head filled with questions. What on earth is a Submittable? How do I write a cover letter? Which poems should I even send in? Needless to say, it was quite the learning curve.

Five years and hundreds of submissions later, I’d like to share the knowledge that I picked up along the way. Over the last two years, I have also had the pleasure of working with Yellow Arrow Publishing as guest editor of the EMBLAZON issue of Yellow Arrow Journal, later joining their editorial staff. Seeing the other side of the submission process was incredibly illuminating, so I will share tips from the perspective of both a writer and an editor. Submissions to the next issue of Yellow Arrow Journal, UNFURL on the process people go through when finding and transforming into their authentic selves, are open until February 28. Learn more about the submissions process and how to submit at https://www.yellowarrowpublishing.com/submissions.

Submit with Care: Choosing Where to Submit

You’ve written some pieces, wrestled with revision, and you’re ready to share them with the world. Where do you start? There are thousands of literary publications out there and it can quickly get overwhelming.

I have three sources that I use to find submission opportunities. Many publications have a social media presence and post about their reading periods. I especially like being able to see the online community that surrounds a publication. I also use ChillSubs, which is an online database of literary publications. It’s a great tool because you can filter your search to find what works best for you. There are other databases, too, like Duotrope. I also look at the acknowledgments page of poetry collections that I read and research any publications listed that I haven’t heard about.

Aside from finding submission opportunities, I urge you to find publications that align with your values and will take care of your work. When I started sending out submissions, I was so excited by the prospect of someone liking my work enough to publish it that I was not especially concerned with who was publishing it. With more experience, I started thinking more about how where I choose to publish could be seen as a reflection of my own values. Since then, I’ve been more intentional about where I submit, evaluating each publication’s website to determine whether we are in alignment. Reviewing the “about” section for every publication, observing whether they’re transparent about their editorial team (often called “the masthead”), and checking their social media presence are a few ways that I vet a journal.

Once I feel comfortable with a publication’s credibility, there are a few other layers I’ve learned to consider. How you approach them is dependent on your preferences and writing goals:

Publications can be in print, digital, or both. I personally don’t prioritize where I submit with this in mind, though it is really exciting to see my work in print!

Many publications charge reading fees, typically ranging from $2.00 to $5.00. This is fairly standard in the literary world, though there are plenty of magazines that are free to submit to. Personally, I tend to submit to free publications.

While a lot of publications don’t have the funds to pay their contributors, there are many who do. How much they pay varies widely. Typically, more established and “prestigious” publications can pay more than others.

Reading is Fundamental: Submission Best Practices

Now you’ve found literary publications that you want to send your work to who are open for submissions. Yay! The most important advice I can give you on the logistics of submitting is to read and follow the guidelines on the submission call.

Each publication has its own rules about how many pieces you can send, formatting, and other important details to keep in mind when submitting, like a theme. Considering the number of submissions most places receive, failing to follow guidelines can be an automatic disqualifier. Reading the guidelines also helps me get a feel for the publication and whether it is somewhere I want to see my work in.

One aspect of the submission process that initially baffled me was the cover letter. Once you get the hang of it, it’s pretty simple, and you should not spend a lot of time writing it. I created a template for myself and adjust it as necessary to save time when submitting. Starting off with a simple “Dear editors” will suffice, unless an editor’s name is listed in the guidelines or easily found on their website. In the body of the letter, I list how many poems I am submitting, their titles, and any content warnings. Most publications ask that you include an author bio in the cover letter, which gives them a glimpse of your previous publications, background, and anything you want to include to give a glimpse of your personality. Additionally, if you have a personal connection with the publication, have published there before, or received an encouraging rejection in the past, these are all details you can include in the cover letter. Otherwise, keep it simple.

Before serving as an editor, I sometimes had a hard time remembering that there are other people on the end of the “submit” button who will actually engage with my work. While editors can feel intimidating, they are humans with their own busy lives. For many publications, editorial staff are volunteers. Be gracious and make the process easier by following guidelines.

The Waiting Game: Keeping Track of Your Submissions

You’ve read and followed all the guidelines, drafted a beautiful cover letter, then clicked submit or sent off that submission email. Now what?

The waiting game begins! Everything is out of your hands and all you can do is wait for a decision. Many literary magazines and journals list how long they take to reply. Transparency around waiting times is another factor that makes me more likely to submit to a publication. From my experience, most places take at least three months to send decisions, though six months is common. Usually, more “high-profile” publications will take at least eight months to respond, but don’t be surprised if over a year goes by due to the volume of submissions they receive. If you are eager for a piece to be out in the world, many journals offer “fast response” options and these typically cost more than standard submissions. I encourage writers to submit the same piece(s) to multiple publications (called “simultaneous submissions”) unless a publication explicitly indicates against it in their guidelines. If a piece gets accepted, be sure to notify any other publications and withdraw it from consideration.

Aside from waiting, you can also keep track of your submissions. When I first started submitting, I did it pretty sparingly and did not see a need to track them. I eventually decided to get more sophisticated with my system and created a spreadsheet, especially to avoid any snafus with simultaneous submissions. My spreadsheet is organized into the following columns: Title, Publication Name, Submission Date, Response Timeline, and Submission Status. I also have a column that notes whether this is a simultaneous submission. I’m a big fan of color coding, so whenever I receive a response, I turn each row (which corresponds to an individual poem) green for accepted, red for rejected, or yellow if I need to withdraw any poems from consideration.

While tracking your submissions is not essential, it has been a useful practice for me because it helps me stay organized. I’m in this for the long haul, and I appreciate having this kind of data to look at over the years. Do what works for you! It should feel useful, not like so much work that it discourages you from submitting.

Give Yourself Grace: Swat the Rejections Like Flies

One aspect of living as a writer that I was not initially prepared for was the magnitude of rejections sent my way. I had a difficult time not taking each rejection personally at first. My stubborn nature served me well in those early moments, because I refused to give up when the desire to create and share was so strong within me. Over time, I also built up a community of writers through social media and attending literary events. Being in community with other writers helped me understand that rejection is a universal writerly experience.

Now that I’ve been on the other side of the process as an editor, I also better understand how incredibly subjective these decisions are. Editors are just people, and they approach your work with all their lived experiences and personal tastes. Another layer of this is the sheer volume of submissions that most publications receive. Even relatively “small” journals receive hundreds of submissions per reading period. Resonant work inevitably gets turned away for reasons that have nothing to do with its quality. One thing to keep an eye out for is that some publications send out “tiered” rejections with feedback and encouragement to send more work their way. Even if you get a rejection from a publication, you should absolutely try again if it is somewhere you truly see your work in alignment with.

When I receive a rejection, I still feel a little sting, but I can brush it off easily now. I try to reframe every rejection as an opportunity. Perhaps the poem could use some revision. Sometimes revisions are obvious right away, sometimes it takes years to see a new direction. What matters most is how you feel about the piece. If you still believe in it without revising, keep submitting. If you have doubts or are less excited about it, try to revise or take a break from submitting that specific piece until your excitement returns. I also strongly believe that each piece has the home it’s meant to be in, so a rejection only means that specific publication was not its home. I recently received an acceptance for a poem I wrote nearly eight years ago that I revised very little. It simply had to make its way to this specific publication, even if that took time. I’ve also realized that a lot of getting published is a numbers game—the more you send out work, the more acceptances you will get.

While I’ve laid out the submission process in a linear way, I want to recognize that submitting your work is no easy feat. It can be time-consuming, tedious, and tiring, especially when rejections start piling up. Sharing your work with anyone is a vulnerable act, and sending your work to editors requires tremendous courage. With all of this in mind, it is essential that you give yourself grace. Don’t let rejections define your worth as a writer. Take a break from submitting when you need to (my longest break was almost a year) and come back when you’re reenergized. Don’t self-reject from publications by not sending your work out, even to the most “prestigious” places. What do you have to lose? Listen to your intuition. I wish you all the best on your submission journey—here’s to many acceptances coming your way!

Leticia Priebe Rocha is a poet, visual artist, and editor. She is the author of the chapbook In Lieu of Heartbreak, This is Like (Bottlecap Press, 2024). Leticia earned her bachelor’s from Tufts University, where she was awarded the 2020 Academy of American Poets University & College Poetry Prize. Born in São Paulo, Brazil, she immigrated to Miami, Florida, at the age of nine and currently resides in the Greater Boston area. Her work has been published in Salamander, Rattle, Pigeon Pages, and elsewhere. Leticia is an editorial associate for Yellow Arrow Publishing and served as guest editor for their EMBLAZON issue. You can find her on Instagram @letiprieberochapoems or her website, leticiaprieberocha.com.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Writing About the Cure

By Charlie Langfur, written October 2024

I have written all my life and learned to trust important events in my life as apt subjects for my writing. One such event that impacted me in a big way was when I was asked to leave high school to be cured of being gay in 1964. The school was Northfield School, an old and distinguished prep school in the sweet rolling hills of northern Massachusetts. I was there on a scholarship from my mother’s boss even though I came from a family always struggling financially.

In 1964, you ask? Back then, being a lesbian was considered to be a disease with the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Psychological Association (APA), but no one told me about it until I was forced to return home to Hasbrouck Heights, New Jersey, to see a psychiatrist every week to be cured. In 1974, the medical establishment altered the diagnostic code for gay people (homosexuals at the time) so that the disorder was no longer considered pathological. The APA made the change first. The fact that there was no such disease (and therefore, no cure) in the 1960s emboldened me and gave me the courage to try and talk my way out of things without talking about being gay at all. The Harvard therapist from Northfield School told me what I said to him was private (between us), but then he and the headmaster sent me home anyway without any warning. “I did not say I was gay, the Northfield doctor did,” I told my New Jersey therapist, but he told me I had to say more to be cured, even though I had no idea what more was any more than he did.

A couple of years after all this, I wrote a short story about what happened called “Curing Sarah,” and in it I tried to make sense of what happened and also to memorialize it for me in some authentic way because it impacted my life in every way possible for many years. Writing about it saved me and helped me understand what happened in a way I could absorb. After I wrote “Curing Sarah,” I began to send it out for publication, even more so after the APA declared gayness was no longer a disease in the 1970s, but the story was always rejected (some with and some without comments). Some years ago, the editor of Zoetrope wrote me, “God, I think this is a funny piece, but I couldn’t possibly publish it.”

But finally in 2012, the University of Southern Kentucky accepted it for Ninepatch: A Creative Journal for Women and Gender Studies. The story is still online and last month my neighbor told me she read and loved it. I’ve reread it and feel it still holds up. The tone matches how it was back then, and it shows how it led me to my life today. I am still writing and sending out my work for publication and recently my poem, “The Way Back,” was nominated for the Best of the Net 2025 by Yellow Arrow Publishing, and I was asked to write a poem for Poetry East’s special issue on Monet (a plumb piece for an organic gardener like me).

Over the years I have learned with writing to never give up on what I have to say. Writing has helped me through good times and bad, reflecting my life as an LGBTQ and green writer, in times when what I had to say was okay and when it was not. Recently Paul Iarobbino, an editor for Bold Voices, who is putting together an anthology of defiant moments in gay lives asked me about putting a reprint of “Curing Sarah” in his publication. He said it had “historical value” but wanted his editors to rework it in a first-person narrative. I politely declined because even though a reprint is a good idea, I know the text is right the way it is now—at least for me it is as a writer and a person. The tone works and so does the style.

Writing helps me pave a way through the difficult, and I try to write my way out of difficulty every chance I get. Nowadays, aging presents many experiences for me to do this, and I finally wrote my first short essay about what an elder is. So, I keep writing and changing and learning anew, and as always I write on.

You can read “Curing Sarah” for yourself at encompass.eku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1027&context=ninepatch.

Charlene Langfur is an LGBTQ and green writer, an organic gardener, a Syracuse University Graduate Writing Fellow in Poetry in 1970 and she has hundred of publications in poetry, fiction and creative non-fiction. She lives in the southern California desert in the Palm Springs oasis.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we BLAZE a path for women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook or Instagram, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

From Baltimore to Rochester: Where I Enjoy Writing in my Neighborhood

By Caroline Kunz, written July 2024

Just like having a brilliant idea and a fully charged laptop, finding the ideal spot to work in is an essential part of the writing process. As a writer and student who always finds herself on the go–from class, to work, to late-night study sessions, to home for break in Upstate New York and back to Baltimore once again–stopping to find locations that facilitate focus, creativity, and inspiration is ever-important.

I believe that any place can be turned into a prime writing location if one possesses the right mindset (and a good classical music playlist or mug of hot tea). However, there are a few locations beyond my desk at home that have proven especially trustworthy. From one writer to another, I hope that my list will resonate with those who enjoy similar spots of their own and inspire those looking for a change of scenery.

Baltimore, Maryland

As a student at Loyola University Maryland, I am lucky to call the beautiful Evergreen campus my second home. Throughout the busyness of my semesters as an English and writing student in the vibrant city of Baltimore, I’ve learned the importance of finding small nooks and crannies to retreat to for writing. In the first few weeks of my freshman year, I picked a little bay window seat in the corner of the English department to call my own. The seat overlooks a courtyard filled with trees, flowers, and students bustling past. I write in this spot year-round, whether the trees outside are yellow and orange in autumn or covered with pink cherry blossoms in the spring. I enjoy the cozy feeling of being tucked away inside Loyola’s expansive Humanities building, stretching my legs out across the length of the cushioned bench and propping a laptop or notebook on my lap. The peace and quiet of a secluded space allow me to be incredibly productive, no matter the type of piece that I’m working on. I’ve written countless essays, literary analyses, creative nonfiction pieces, and poems (often inspired by the views outside) here over the past three years, and I look forward to returning in August for my last.

Just about a 10-minute walk from campus lies Sherwood Gardens. The park features open green spaces, shady trees, and lush flowers. The vibrant array of tulips that blooms in early May is particularly striking. When looking for a change of scene, my friends and I will grab our backpacks and a picnic blanket and take a walk to Sherwood. Oftentimes, my professors will hold their classes here when the tulips are in peak bloom. Sitting there beneath the shade of a towering tree is like a breath of fresh air, the garden bringing with it a sense of inspiration and focus that contrasts that of the standard classroom. I find that this is my favorite place to complete assignments relating to the outdoors, whether it be a spring-inspired poem or an analysis of the nature imagery in William Shakespeare’s As You like It. When my scenery matches the tone of my work, I feel a deeper sense of connection to my writing.

Rochester, New York

When returning home to Rochester for semester breaks, I look forward to the city’s impeccable coffee shop scene. Coffee shops are some of my favorite places to write—the din of chatter, the smell of fresh espresso, the eclectic music and decor. When writing essays and analyses, I tend to need a quieter space to work. However, for poetry, journaling, and creative pieces, I crave the bustling, communal atmosphere of a coffee shop. I gravitate toward those on Park Avenue, a Rochester street known for its historic homes, eclectic art scene, and unique restaurants and shops. Café Sasso is my go-to shop on the winding street, featuring walls covered ceiling to floor with paintings by local artists and plenty of tables and window seats for writing. I usually pick a small table in the corner, order an iced “Gatsby” (a latte with lavender and white chocolate), and get to work. I become inspired by the art, the view of Park Avenue outside, and of course, the people watching. In fact, during a previous semester, I was assigned by a poetry professor over spring break to take a line that I’d overheard from someone else’s conversation and use it in my next poem. I couldn’t think of a more ideal environment than a coffee shop to complete this assignment. The results from this experiment were exciting and refreshing compared to the poems I’d written previously. Since then, I’ve continuously found ideas for poems and short stories among the coffee shop patrons that sit beside me.

Another favorite street in my hometown is Rochester’s Neighborhood of the Arts. Located within the neighborhood is Writers and Books, a literary arts nonprofit and hidden gem of a place. Writers and Books fosters the perfect environment for inspired writing, from the giant wooden pencil outside the front of the building, to the inviting, bookshelf-lined rooms within. The nonprofit aims to promote reading and writing as lifelong passions by offering workshops, community writing groups, open writing spaces, and guest lectures to locals of all ages. I was lucky enough to spend nearly every day of my summer at Writers and Books last year while I served as a SummerWrite intern, helping to coordinate the nonprofit’s summer writing classes for young students in the area. These students found such joy in getting to write alongside those with a mutual passion for the literary arts. Watching their excitement grow throughout the summer reminded me of the benefits of writing in concentrated spaces like this. For those looking to strengthen their writing skills with a workshop or write in a community-oriented setting, I can’t recommend literary arts nonprofits and writing centers enough.

Final Thoughts: Where do You Write?

As I stated previously, the most important thing is that no matter where we write—from coffee shops to airport gates to local parks—we possess the right mindset. With grit, determination, and great zeal for what we do, we writers have the potential to turn even the most unlikely of places into a successful writing location. Whenever I begin writing in a new place, or I find that I’m struggling to focus, I remember author Isabel Allende’s quote, “Show up, show up, show up, and after a while the muse shows up, too.” In other words, no matter where you choose to write, keep showing up. Keep at it, even when the poem, chapter, or essay you’re working on seems an impossible task. Keep an open mind, and inspiration may come to you in the places you least expected.

Caroline Kunz (she/her) is a rising senior at Loyola University Maryland, where she studies English and writing on a pre-MAT track. She enjoys traveling, scouting out new coffee shops, and of course, reading and writing. As an aspiring educator, she hopes to share her love of the written word with future generations of students. Her current favorite authors include Taylor Jenkins Reid and Celeste Ng.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we AMPLIFY women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

The Evolution of My Writing

By Amaya Lambert, written April 2024

Well, writing evolves throughout time.

I believe that your writing changes forms as you grow into it. When I started out writing, my stories took a more comedic turn; sparkled with humor and jests alongside wacky situations that made me burst out laughing as a child.

I read middle grade books. The Percy Jackson series. The Kane Chronicles. The Monster High series. All targeted to young children with big imaginations and short attention spans. One of my favorite books of all time was the Web of Magic series where the power of friendship triumphs over.

I emulated that in my writing.

Then came high school, where young adult books grew popular. I grabbed fantasy books from my sister’s shelves. I begged my parents to let me read Game of Thrones. I devoured the Court of Thorns and Roses and An Ember in the Ashes.

I played more mature games with violence and sexuality. My prose grew, my vocabulary expanded.

I emulated that in my writing.

It wasn’t until my junior year of college that I seriously considered the form of my writing, what my style should be and how it will dictate my career for years to come.

I fell in love with lyrical and poetic prose. I realized my knack for emotionally charged stories and complex characters. I discovered my fascination with the profound and the psychanalysis of humanity. I grabbed books that challenged my mind and made me think about the world differently. I learned about my place in this world and how I can either meet or exceed its expectations.

My writing takes on the form of song, almost lyrical and melodious in its prose. I think carefully about how the words fit together and what type of picture it paints. I take inspiration from song lyrics, poems, quotes, and movie soundtracks. I think about the mood of my story, what atmosphere I’m creating, what tone the words speak.

I meticulously go over my pieces, creatively constructing a symphony of prose.

Some of my favorite lines were that of:

“She wants to run, but her feet remain on the ground. It’s like her mind says one thing but her heart says another.”

“There’s something rotten in the air, congealing.”

The construction of sentences and piecing of words takes form in my writing. I can see the emotions conveyed in the words. I can see what type of messages they evoke.

The evolution of writing is an integral process for any creative. Our writing grows as we grow. Many authors have certain types of branding to stick onto their shifting forms. It is one of the reasons as to why many of my favorite authors have a certain niche woven into their words. To make up for the change of writing, they make sure the reader can recognize their style.

I’ve been reading Chinese light novels translated by passionate fans. Though the author’s style dramatically changed from her first novel, The Scum Villian’s Self-Saving System, to her latest work, Heaven Official’s Blessing; I can see traces of her signature style in both novels. Her multifaceted characters. A focus on the internal arc of the main characters. The love and attention to the side characters. The slow burn of the romance relationship. Even if she changed her writing form, I’d still find her within the novel’s pages.

There’s a reason why fans will have authors on their immediate purchase list because they fell in love with their signature style. They say as you begin to write, you grow more comfortable in words. There’s a shift in language, a change in prose, and your writing form evolves with time and effort.

I hope in time when my writing twists and turns and is still able to retain its original concept, as a song.

Amaya Lambert is a senior at Towson University, studying English and creative writing. She loves a good book, slow music, and tasty food. When she isn’t reading, she’s writing, lost in her inner world. Amaya tutored for her high school’s writing center and the elementary school across from it. One of her proudest accomplishments is winning second place in a writing competition in the seventh grade.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women-identifying writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we AMPLIFY women-identifying creatives this year by purchasing one of our publications or a workshop from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, for yourself or as a gift, joining our newsletter, following us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter, or subscribing to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Why is Creative Nonfiction Important?

By Mel Silberger, written March 2024

Creative nonfiction is my favorite genre to write! I love the opportunity to write about moments in my life with a creative lens, allowing me to combine my outward experiences with my inward thought processes and feelings. At times, creative nonfiction serves as an outlet to discuss the topics I am most passionate about and the interactions they have brought me, whereas in others, I can write about the vulnerable and life-changing moments I have undergone.

Difference Between Fiction and Creative Nonfiction

First, it is important to establish the differences between fiction and creative nonfiction. Fiction can be described as a story about (possibly) pretend characters in a (possibly) pretend setting with a (possibly) pretend plot; there can be elements of truth, such as the setting being a real place or characters being real people, but it overall does not fully reflect experiences as they factually happened.

Creative nonfiction, on the other hand, is about real people in a real setting with a plot that really happened. When writing creative nonfiction, the author has the creative freedom to combine events that have happened with their thought processes and emotions in those moments, but they must adhere to the accurate retelling of events as truthfully as possible.

Purpose of Creative Nonfiction

The purpose of creative nonfiction is to convey a story’s facts and information in a fiction-like manner, entertaining the reader and allowing them to understand their author’s perspective. In other words, creative nonfiction lets the reader get a firsthand account of what the author was thinking throughout the experience or moment they are writing about. The author becomes a character themselves and takes their reader through the events that unfold.

When writing creative nonfiction, the author has the obligation to tell the events as accurately as they happened, but the creative freedom to retell them with attention to specific details or thought processes. Through their description of these events, the author’s voice is able to shine through for the reader to understand.

Creative nonfiction encapsulates countless forms of writing, such as journalism, memoirs, personal essays, and biographies.

Importance of Creative Nonfiction