Yellow Arrow Publishing Blog

An Interview with Sofía Aguilar

By Melissa Nunez, written January 2022

Sofía Aguilar is a Chicana writer and editor based in Los Angeles, California. She is an alum of WriteGirl, an LA-based creative writing and mentoring organization that empowers girls and nonbinary teens through mentoring and monthly creative writing workshops, and is still active within that collaborative community. She has published an impressive body of online work ranging from poetry and essays celebrating her heritage to commentary on female and Latin@ representation in pop culture and the media for publications like LatinaMediaCo and HipLatina. Her passion for uplifting the voices of marginalized writers and contributing to a conversation of positive change was evident from the start.

Sofía is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of Mag 20/20. This past December, she self-published her first poetry chapbook titled STREAMING SERVICE: golden shovels made for tv. I found Sofía’s work resonant and relatable, especially her thoughts and themes surrounding Latin@ culture. Her published essays like “Decolonizing My Latina Hair: How I Learned to Love the Locks White America Wanted Me to Tame” (Offcultured, 2021) and “motherland” (Jupiter Review, 2021) voice issues relevant to many descendants of the Latin@ diaspora. As a writer with a wide range of talents, I was very interested in hearing more about where she finds her motivation and inspiration.

I was able to chat with Sofía during her time in residency with the Sandra Cisneros Fellowship in Tepoztlán, Mexico—one of the many honors she has received in her writing career. The bright room and window mountain scene served as a backdrop to our conversation and were matched by her vibrant energy.

As an organization with a similar mission, Yellow Arrow Publishing was very excited to hear about the WriteGirl organization. Can you tell me about your experience with WriteGirl and what makes it so successful?

I was referred to WriteGirl by a high school guidance counselor because of my interest in writing. My peers were more STEM-oriented, and he saw the need for a creative community of writers I could relate to.

I met so many amazing people through WriteGirl. The mentees and staff, the women mentors, are so incredible. I cannot say enough good things about it. The workshops are designed to introduce you to all these different genres of writing, not just poetry, and [they] opened my whole world. From an early age, I was exposed to these things I wouldn’t have been otherwise. That’s why I write in so many genres. I write hybrid works and love pushing the boundaries of genre. Aside from writing, it also helped me with professional skills (public speaking and networking) that I still use to this day. And I’m still learning so much. I’m still involved with the program as a volunteer and staff member.

I think it is successful because it is led by so many incredible people. They are passionate about their work, and it shows in everything that they do. There is so much deliberate care taken in the building of relationships. I consider myself so lucky to work with them and help foster the next generation. Giving back to a community that gave me so much. They told me my words mattered and that my voice could resonate with people at a time when I most needed to hear it. The whole structure invites people to come back so the work continues.

What do you love most about writing?

I’ve always wanted to tell stories. I’ve always loved words and language. From an early age, I knew I loved creating new worlds and fantastical things. But when I was younger, I wasn’t exposed to people who resonated with me or reflected my own experience. Not until reading The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros. She captures the Mexican American experience so beautifully. It was so impactful, and I wanted to do that. To give representation to someone else who needed it. I wanted to see a world where you shouldn’t have to wait to read a book that represents you. I love that I get to celebrate my heritage, my journey, and uplift women, shed light on social justice issues when I write.

You mentioned the amazing author, Sandra Cisneros. Who else has served as inspiration in your writing journey?

Everything Sandra Cisneros has ever written has become biblical to me. Her work is the kind that you can keep coming back to and learn new things, which is rare for me. I read her at a point where I needed her, and she has become such a relevant figure in my life. Other writers that have really inspired me are Jane Austen, who has impacted the way I look at character and dialogue. Maggie Nelson, in her telling of stories through vignettes. It can be really intimidating to see people writing these huge sagas, and I thought I couldn’t be a writer without writing this huge book. She showed me another way to do it. Salvadoran poet Yesika Salgado has greatly inspired my poetry. Janel Pineda (friend and WriteGirl alum) is another Salvadoran poet I admire. I enjoy reading writers across the Latin@ diaspora.

When you write about culture, how do you balance the honoring of family and people with the critical aspect that comes with acknowledging things (customs/values/mores) that need to change?

One example of this is the way I use the Spanish language in my writing. I don’t italicize Spanish words because it is a language equal to English. But I also talk about (in “motherland”) how Spanish is a colonizer language. Spanish is beautiful and romantic and the language of our people, but we have to acknowledge that it is so widespread across Latin America because of colonization. On the other hand, in the United States, Spanish is seen as an enemy language, not to be spoken in certain areas. It is such a complicated dichotomy. There are some contexts in which speaking Spanish feels like something that brings shame or needs to be hidden away, and in this aspect, we should empower it. But also, it is used to silence Indigenous languages. So, there is a need to both celebrate and question the history of the language.

What work in progress are you most excited about?

I have so many ideas for so many things. I have so much to say, and so many ways to say them. Right now, I’m most excited about the novel in verse I am writing. There are so many possibilities for the characters and story. It is challenging but rewarding.

What advice would you give other women writers?

Write the story you haven’t read yet but want to read. That’s what is motivating my novel in verse. Nobody has written this story and it made me ask, why? This is my biggest motivator for writing. When I haven’t seen something done or done well, I want to be the answer to that question. Write the stories you want other people to read. What the world is missing. That urgency is so helpful to the writing process. Write what we need.

And also, rest. This is something I have learned during this residency. I have come to see writing as a service. We are storytellers. Someone here said something like, “Writers think they are not serving if they are not writing. But part of the writing process is to rest. Sit in silence with yourself.” So, you don’t have to be productive all the time. You are allowed to rest.

You can follow Sofía on Twitter @sofiaxaguilar and find more information about her writing career on her website. I am looking forward to reading more of her words. To see her writing what the world needs.

Melissa Nunez is a homeschooling mother of three from the Rio Grande Valley. Her essays and poetry have appeared in Sledgehammer Lit, Yellow Arrow Journal, and others. She is also a staff writer for Alebrijes Review. Her writing is inspired by observation of the natural world, the dynamics of relationships, and the question of belonging. You can follow her on Twitter @MelissaKNunez.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

You can support us as we AWAKEN in a variety of ways: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 102, Glen Arm, MD 21057). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Lunchbox Moments: A Zine to Emphasize the Importance of Community

By Rachel Vinyard

We aim to provide a platform for AAPI voices to express:

1. anger and shame roused by racist microaggressions we may have experienced in relation to our cultural foods,

2. pride, joy, and other emotions relating to our cultural foods, and

3. how we have integrated deeper practices emerging from these experiences to honor those emotions.

When I was first introduced to the Lunchbox Moments zine and its mission, I was ecstatic to learn more. I was excited to know that there was a zine that gave the AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islanders) community a platform to speak their truths and talk about very real issues that haven’t been widely discussed until recently. When I sat down to read Lunchbox Moments, it felt as though I were experiencing a world that was unique from mine. A world of fear, shame, and hurt brought on by ignorant, unapologetic people. Diversity is important for storytelling because every story is worth being heard.

Food is an especially important thing to immigrants because it keeps them connected to their culture. Lunchbox Moments is a zine that eloquently and beautifully portrays real stories about the struggles and xenophobia in the AAPI community regarding their food culture. Created by Anthony Shu, Diann Leo-Omine, and Shirley Huey, this zine showcases 26 AAPI writers, including Christine Hsu whose creative nonfiction piece “Mother Tongues of Confusion, Shame, and Love” appeared in Yellow Arrow Journal, Vol. IV, No. 1, Renascence. The zine is a compilation of a variety of different experiences regarding food in the AAPI community. Lunchbox Moments also supports Chinatown’s Community Development Center (CCDC) in San Francisco.

Anthony, Diann, and Shirley recently took the time to answer some questions for us.

Please introduce yourselves and tell us how you decided to work together to create Lunchbox Moments. Why Lunchbox Moments?

Anthony: We met at the San Francisco Cooking School’s Food Media Lab in 2019 and had always wanted to work on a project together. Lunchbox Moments was born out of the pandemic and discussions of race and inequality that dominated 2020. As we went through various ideas on how we could collaborate, we witnessed increased attention on Anti-Asian hate crimes in early 2021. For me, this time period reinstated the importance of uplifting Asian American voices because our stories often go untold. How can we address discrimination against AAPI communities when our country lacks a shared discourse or knowledge of who this group encompasses/our history/our struggles? The theme of lunchbox moments was a way for us to combine our interests in food/food media with sharing Asian American experiences.

Diann: Lunchbox Moments came about because of the perfect storm, really. Food media is still overwhelmingly nondiverse, even as discussions on cultural appropriation and who can make whose culture’s food have begun to take shape. Asian Americans have also long been silenced or perceived as apolitical, so creating this platform was our “lane” in the activist sense.

Shirley: From our first moment of connecting in 2019, Diann, Anthony, and I have been talking about our respective and mutual interests and experiences in food and cooking—personal and professional (we each have worked in some capacity in restaurants/food), writing, and the political and cultural intersections of those subjects. We each love food deeply and find personal meaning and joy in cooking. Everything starts there. It’s a bit of a cliché to say this, but I do believe that important conversations often begin at the kitchen or dinner table. Our story is no different: we started talking about our experiences with/in food and our respective interests in food and writing over several lunches (a memorable one at Sai Jai Thai in San Francisco).

On Lunchbox Moments, I wanted to work on something that would, hopefully, be meaningful to readers, relevant to the moment, and also doable. We had real-life constraints of various kinds, but we also wanted to make this work. Speaking for myself, I wasn’t thinking about a platform; I’ve never been particularly quiet about where I stand on political issues. What I did want, though, was to do good work in line with my values, help create a platform for others to tell good stories, and raise money for communities affected deeply by the Covid-19 pandemic.

What was the most challenging part about putting the zine together? How did you address the challenge?

Diann: From a logistics angle, we conceptualized and executed the project entirely remotely. In fact, the first time we were all able to gather in person since meeting in 2019 was only recently. We staked ourselves to an ambitious publication date (about seven months from concept to execution). From an emotional angle, the increase of violence against Asian Americans came to a heartbreaking crescendo with the Atlanta and Indianapolis shootings, not to mention the media’s sudden reportage of violence against Asian elders and especially in the San Francisco Bay Area. We were editing the selected pieces during that time period, and the editorial process was both a cathartic way to process the communal grief but also simultaneously traumatizing. The challenge was keeping ourselves motivated, remotely, when sometimes I think all we wanted was to fall apart or hide underground when our communities were under attack, but we pressed on because we knew the work had to be done.

Shirley: We came together to work on this project because of what we observed during (and before) the pandemic—the negative rhetoric and physical violence directed at Asian Americans. As the pandemic went on, the relentless news coverage of what was happening affected each of us deeply. We were editors, yes, but we were also people observing and experiencing what was happening in the world around us and to our communities, processing the collective grief and also our own individual personal griefs, which were real and deep.

How did we deal with the challenge? I think the most critical thing was that we really trusted each other and held each other through it as colleagues/collaborators. We had weekly meetings to keep us on track, and at certain points, one of us would say, “Hey guys, I just can’t manage this right now.” And the others of us would say, and we meant it, “No problem, you take a little time away from the project. We’ll hold it and keep it going.”

How was Lunchbox Moments conceptualized? What inspired you most to create the zine?

Anthony: When we first thought about this theme, we learned from articles in NPR and Eater that challenged the value of stories about lunchbox moments. These articles argued that the traditional lunchbox moment narrative excluded many AAPI individuals who never have these moments and overemphasized feelings of shame. In response, we broadened our language in our call for submissions. It was inspiring to see the various pieces that came in and how people interpreted the lunchbox moments theme. We heard from writers and artists who had always been proud of their lunch, who felt their lunch hadn’t been Asian enough, and who shared about lunchbox moments in fields beyond food like language and familial relationships.

Diann: Yes, we wanted to shift focus from the stinky food narratives that have been so pervasive that lunchbox moments have become a trope. We sought out narratives that we found most interesting was how many people had lunchbox moments within the community or within themselves. On a personal note, I lost my grandmother and gave birth to my first child in the midst of our short, but ambitious publication process. For me, the zine became a sort of driving force tribute to both my grandmother and my child—of memories past and future.

Shirley: What inspired me the most at the very beginning was the opportunity to showcase stories featuring Asian American writers, to have some creative control over the project, and to do so in a way that was in service to the larger Asian American community. This was a remarkable opportunity to work with my really talented coeditors and friends, to work on compelling subject matter, and to uplift the work of our wonderful writers and artists. It was also an opportunity to learn about what it takes to bring something like this into being.

What do you hope that your readers take away from Lunchbox Moments?

Anthony: I hope people recognize the diversity in the stories told, especially in the range of emotions shared. These aren’t just stories about lunchbox moments focused on shame that elicit rage, guilt, or sadness. To me, this isn’t a collection of stories about Asian Americans being victims of discrimination. Instead, each piece complicates our definitions of being Asian American.

Diann: I hope readers come away with more questions than answers regarding Asian American identity. The Asian American identity has long been boxed in by the “model minority” myth and is not a monolith, and disparities abound between ethnicity, class, color, and generation. Even rereading the stories again today, there are different meanings I pick up every time.

Shirley: What Diann and Anthony said. And also, for some readers, I hope that they come away with a sense of recognition and connection to the stories told. I’ve just been asked to speak to a college-level class on Asian American women writers about Lunchbox Moments and feel so gratified to know that students are reading this work. I hope that readers can see the power of sharing their personal experiences—whatever they are and however they fit into or don’t fit into a particular trope around what it means to be Asian American. And honestly, I really hope that readers come away with a hunger for new food experiences as well as a recognition that meaningful stories about our lives can come in many forms, including about something as seemingly mundane as our everyday interactions with food.

How did you know that storytelling through and about food has power?

Anthony: Food is an important way for immigrants and their descendants to connect to their cultures. In the collection, I witness the different ways this connection is interpreted, lost, or reinforced, often across generations. I feel that many people can connect to this idea of food traditions changing over time. Also, since announcing the zine, I’ve spoken to many people, not just AAPI individuals, who have strong memories about school lunch and the cafeteria. A common theme has been being bullied for receiving free or reduced-price lunch. It seems like there is something formative in those childhood meals.

Diann: With the popularity of platforms like Instagram and Yelp, foodie culture relegates food for its consumptive value. There’s an adrenaline rush in waiting in line for three hours for the next hottest food trend, of taking so many photos the meal gets cold, and then getting your followers to obsess over the geotag location. In our stories, however, food is a character. Food is symbolic, food is catharsis. Food inspires all types of emotions.

Shirley: There are moments in our lives that we never forget—the big moments—the weddings, the births, the deaths, the loves, the trials and tribulations. And then there is the smell of freshly baked chocolate chip cookies. The sweetness of ripe summer strawberries encased in soft whipped cream. The pungent smell of savory salted fish and chicken fried rice. But the two—the big moments and the smaller moments—are not unique and separate. As Diann says so beautifully, food is a character, yes. Food and our interactions with it reveal things about ourselves as characters that are meaningful. This is especially true for some who grow up in families that are not particularly verbal or direct in communicating about emotions and feelings—except about food. When this is so, I think showcasing food in the storytelling can be particularly powerful.

Why did you choose to partner with San Francisco’s CCDC?

Anthony: To clarify, we are not partners with the organization. We just named them as our beneficiary. They operated two iterations of Feed + Fuel Chinatown over the last year and a half, which was a program that combined supporting Chinatown’s residents and its businesses, especially its restaurants. We wanted to respond to the xenophobia that has hurt Chinatown businesses since the start of Covid-19 (and before shutdowns in the U.S.).

Diann: People may not be aware of the racist, segregated history that allowed for the creation of Chinatown and laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Chinese were thereby limited in what occupations they could take, and cooking was one of them. Chinatown and Chinese people have long been synonymous for immigrant communities and Asians, so when [then-President Donald] Trump spouted vitriol like “Kung Flu” and “Chinese virus,” it undoubtedly felt like an invisible history was repeating itself. Yet that time period is not that long ago, as my parents were both born in Chinatown and would have benefitted from an organization like the CCDC if it existed back then. So our decision to donate funds to CCDC was a way of giving back to those historical immigrant roots.

Shirley: We actually put a lot of thought and research into it, knowing that whatever organization we chose needed to be one that the three of us each connected with and supported. Diann and I both grew up in San Francisco, with ties to Chinatown. Anthony grew up in the South Bay, with less of a personal connection to San Francisco Chinatown. We also conceived of the project as having a national focus; we were looking for diverse contributors, not just in terms of cultural identities, but also regional location. So we initially set out to find a beneficiary that contributed to the needs of immigrant restaurant workers, supported Asian American communities, and had a national focus. We looked at entities doing direct service and doing other kinds of more capacity building work. We didn’t want to default to a San Francisco Bay Area based organization just because we happened to be located here. We ended up choosing CCDC because of its long-standing work in San Francisco Chinatown and its tremendous work on the Feed + Fuel program, feeding low-income folks living in Chinatown single room occupancy hotels. We recognize that San Francisco Chinatown-based organizations have been at the forefront of advocacy on behalf of Chinese Americans and Asian Americans nationwide since the beginning of Asian immigration to America.

In what ways can readers support the Asian American community during the pandemic? After the pandemic?

Anthony: Over the last year, I was shocked to have discussions with individuals who never or rarely thought about discrimination against Asian Americans. I hope we can learn more about both the history/legacy of discrimination against AAPI communities and also the parts of these cultures that inspire pride and celebration.

Diann: During and after the pandemic, readers can support the community by patronizing Asian American businesses and following Asian American creators on social media. Of course, the issues are systemic and deeper than capitalism or social media algorithms. Readers can, as Anthony suggested, dig into the history/legacy of discrimination—read anything by Helen Zia or Ronald Takaki and watch the Asian Americans documentary on PBS.

Shirley: Good question. There are many ways in which readers can support the Asian American community during and after the pandemic, some of which Anthony and Diann have already touched on. I think reading about history and discrimination and patronizing Asian American owned businesses are important. I would also add a few more things: slow down and listen. The experiences of Asian Americans (if we can still use that term—a conversation for another time) are multiple and diverse, and we must make space to hear about them. Also: history is now. So when you go to read about the history of Asian Americans, remember to look for sources about what is happening now—and not just about shootings and violence perpetrated against us. Try reading Hyphen magazine, Asian American Writers Workshop’s The Margins. See what’s happening at sites like Asian Americans Advancing Justice—Asian Law Caucus and Asian Prisoner Support Committee. Stand up for people if you see them being bullied or harassed. I recommend the Hollaback Bystander Intervention training.

Have you experienced any lunchbox moments of your own as Asian Americans in a workplace or school setting?

Diann: I’ve experienced my own lunchbox moments from outside but particularly within the Asian American community—from the expectations of me being able to fold immaculately crimped dumplings or steam a perfectly tender whole fish. I never learned to use chopsticks the proper way, and I got called out recently about that—I retorted back to the person that, well, at least I knew how to eat. Even for someone who has cooked professionally, this idea/ideal of perfection while performing Asian identity is stifling, and cuts into complex memories of family, language, and diaspora. It’s something I’m still grappling with to this day.

Shirley: I have experienced lunchbox moments mostly in the workplace or private context from people who would never identify as racist in any way. They were microaggressions—for example, expectations that I would know something about a particular kind of frozen dumplings “because you’re Chinese, you should know” said with absolutely no irony. Another time, the person in charge of ordering a work lunch refused to even consider Chinese food “because it’s so greasy.” She clearly had never had beautiful, nongreasy, delicious Chinese food. I don’t know if this relates to lunchbox moments, but I definitely relate to Diann’s grappling with internal perfectionism and its relation to creation of food. Also, even the notion of perfection could be subject to greater scrutiny. What is perfection in light of differing experiences of what is authentic and real, both in terms of food and in terms of identity?

Will there be a follow-up publication?

Anthony: We are undecided at this time but thank everyone for their generous support.

Diann: (laughs) We had joked that maybe we could start a podcast themed around current events in food media. Stay tuned. In all seriousness, as Anthony had said, we are undecided at this time.

Shirley: Ha, Diann. I would just add that we are undecided, but you know, if someone chose to fund our working together and you know, perhaps help mentor us on the next publication, that might help move us in a certain direction.

Shirley Huey (she/her) is a Chinese-American writer, editor, consultant, daughter, sister, friend, collaborator, cook, music and theater lover, cat mom, and former civil rights attorney. She believes that place and race matter and that we can make the world a better place from wherever we are, right at this moment. Born and raised in San Francisco, Shirley’s writing can be found in such publications as Berkeleyside, Catapult, Panorama: The Journal of Intelligent Travel, The Universal Asian, and Endangered Species, Enduring Values, an anthology of San Francisco writers and artists of color. She has received fellowships from VONA, Kearny Street Workshop, SF Writers Grotto’s Rooted and Written, and Mesa Refuge, and is working on a memoir in essays about food, family, and social justice.

Diann Leo-Omine (she/her) is a culinary arts creative and writer rooted in San Francisco (Ramaytush Ohlone land) and the colorfully boisterous Toisanese diaspora. She now resides in the North Central Valley (Nisenan land), in between the ocean and the mountains. Her writing can be found in The Universal Asian and the Write Now SF anthology Essential Truths.

Anthony Shu’s (he/his) first experience in the culinary world came as a breakfast cook at a nonprofit summer program where the “kitchen” consisted of a Presto griddle set up outdoors. He graduated from Princeton University in 2016 and after a brief career in more professional kitchens, Anthony started working at Second Harvest of Silicon Valley and has been focused on client storytelling and multimedia production for the last few years. Also a freelance food writer, his work has been published in Eater SF and the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

Rachel Vinyard is an emerging author from Maryland and a publications intern at Yellow Arrow Publishing. She is working towards her Bachelor’s degree in English at Towson University and has been published in the literary magazine Grub Street. She was previously the fiction editor of Grub Street and hopes to continue editing in the future. Rachel is also a mental health advocate and aims to spread awareness of mental health issues through literature. You can find her on Twitter @RikkiTikkiSavvi and on Instagram @merridian.official.

*****

Thank you to Anthony, Diann, and Shirley for taking the time to thoughtfully answer Rachel’s questions. Please visit the Lunchbox Moments website to learn more about this initiative and purchase a PDF copy of the zine today!

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. Thank you for supporting independent publishing. Visit yellowarrowpublishing.com to learn more about submitting, volunteering, and donating.

Taking Moments to Listen: A Conversation with Ute Carson

“I’m never someone who sends out a mission to my readers, but I want them to stop a moment when they read and maybe say: what do the words mean? Could that be applied to something in my life?”

Ute Carson, German-born, now Austin, Texas resident, is the author of Yellow Arrow Publishing’s next chapbook, Listen. The desire she has for her readers to pause and engage with her words is evident within the lines of the 44 included poems. Listen’s imagery forces readers to stop and sit with her words for a few moments before continuing to evaluate the book’s themes: engaging with nature and loved ones and reflecting on one’s past experiences and their subsequent formative effects on the ensuing years. Ute’s words convey to her readers her enchantment with the world around us during every stage of our existence.

A writer from youth, Ute has published two novels, a novella, a volume of stories, four collections of poetry, and numerous essays here and abroad. Her poetry was twice nominated for the Pushcart Award. Yellow Arrow is privileged to publish Listen, now available for PRESALE (click here for wholesale prices) and released October 12, 2021. You can find out more about Ute at utecarson.com. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram for Friday sneak peeks into Listen from this week until October 8. Recently Editorial Associate Siobhan McKenna took some time to get to know Ute and the significance of Listen.

As a young child in Germany during World War II, Ute was bombarded by the tragedies of the world: her father died in the war before she was born, her mother’s second husband was also killed, her two uncles perished in the brutal Stalingrad winter, and she, her mother, and grandmothers were forced to flee their home—losing everything—as the Russians invaded. Yet, Ute remembers, “In spite of a very dramatic childhood, I was embedded in this incredible love. Even when I saw the most terrible things. I saw for the first time wounded soldiers—crying, dying. And that left a deep impression on me. But at the same time, I was always protected by these females around me, so I was able to choose that same influence that warms and protects you all through my life. And I have tried to impart that to my children and my children’s children.”

We carry the house of childhood within us,

and spying through its translucent walls,

we keep life at a distance or embrace it.

(The House of Childhood)

As the women in her family worked together to shelter Ute from the dangerous times, they told stories, and Ute began to understand the power of writing. “My maternal grandmother, my father’s mother, and my mother were all steeped in German poetry, stories, and I absorbed all that.” In addition to the songs and tales that she was “fed,” Ute’s writing was influenced by an elementary school teacher who “always ended each class with a story” and helped her publish her first story in the German magazine, Der Tierfreund (Friend of Animals). From that moment on, Ute says she has never stopped writing.

We all have been warmed by a fire we did not build.

Parents set a fire

that sends out sparks to dispel darkness,

and lights the way for the young into the world.

(Flames Rising)

In Listen, Ute weaves a poignant narrative of what it means to be engaged with the world by drawing on her childhood influences, educational background, and experiences as a friend, lover, and grandparent. Many of her poems emphasize understanding one’s place in the life span and the collective conflicts we face as humans. This is only fitting as Ute herself studied various psychological theories and was a clinical hypnotist at a trauma center in Austin for many years. Being able to write about universal struggles is an important aspect of Ute’s poem as she often changes perspective or leaves the speaker deliberately ambiguous. In the poem “She Still Lives Here,” Ute writes as a husband mourning the loss of his wife. “I changed perspectives because I try to generalize. I don’t always bring it back to me.” She continues to say that writing poetry “is not just telling about your experience, which is very valuable—you start with your experience—but your experience has to be formed. It’s not enough to just put it out there. What you do as a writer and a poet is to transform [the experience] into something that is universally human and that’s how it appeals to my readers (not just to my family) who can then relate my personal experience to their own. I am a critic of people who just write about their experience and do not attempt to empathize to the human condition.”

How do we venture into the lives of others

and still remain true to ourselves?

[. . .]

We build barriers, high and solid,

wire fences between properties,

[. . .]

My favorites are the ones made of rope

that I can climb over or crawl under.

(Self and Others)

In addition, many of Ute’s poems use her current role as a grandparent to view the world. In “Breaking Away,” Ute writes that grandparents are the “hub in the wheel of life” as they “relieve busy parents” and “indulge the young.” Ute believes that grandparenthood is easier than parenthood and says that she loved being a parent, but between teaching, writing, getting a graduate degree, and having three girls that she was “always torn in different directions.” Now, when one of her grandchildren “bursts through the door everything else can be wiped away. Even the ailments, which you know when you are 80 years old, they are there, and you forget for a moment because a child beams and throws [themselves] into your arms.” She says it is not simply that you have more time, but also more “psychic energy” to spend on your grandchildren because “you are no longer preoccupied with your development” and the questions of, “Who am I as a writer? Who am I as a parent? Who am I as a wife?” Because “as a grandparent, you have pretty much shed that search for the self and know who you are. And that is very comforting because you can then convey that to your grandchildren.”

How difficult it is to picture our parents as young lovers,

or the bearded homeless man as a smooth-skinned baby.

It takes a leap of imagination

to peer through the fog of time

and see each stage in life

linked from first to last.

(Snapshot in Time)

But despite loving the view from grandparenthood, Ute also writes of the limits that she has encountered with aging. In “Relinquishment” she laments no longer being able to wear her favorite heels and in “The New Normal” attempts to race her grandson only to find that she immediately falls. When asked about this experience, she says, “I had it in my mind that I had been a runner and that I could still run, and I fell absolutely flat and that’s the flexibility we need to learn in old age. That yes, you still know how it was when you were able to run, but you can’t do that anymore . . . there are final limits.”

The wind of mortality

sweeps through the woods,

stripping away leaves

and downing limbs.

Sap turns to bleeding tears.

(Bleeding Trees)

Throughout the collection, Ute blends childhood memories with her insight that comes with aging, which begs the question: What does it mean to live a full life? To this, Ute answers that she loves being able to care for her animals and garden. She snuggles with her cat, grooms her horses, and tells her roses, “I’m sorry, but you need a haircut.” But, above all, she says that a full life to her has meant her experiences with her mate. “My husband—who has been at my side for so long. We have had things that we have had to struggle with in terms of ailments and all kinds, but we do life together still and we still very much enjoy what we’ve always enjoyed. My husband had an incredibly busy professional life. And, not that we weren’t connected during that time, but there is a different connection now. Now the time together that we spend [is not between] him flying off to the next meeting or to colleagues. It’s a kind of circle that you come around to appreciate your partner—whoever it is . . . I don’t mean you have to have one [singular], but the partner that comes around as we age is important. Someone that you can fold wash with and do other everyday tasks even when you’re old.” She adds, “[My husband and I] still fight over politics. We still have our own things that we do. But it is still valuable time spent together, [we ask] how do we want to structure our last years together? And that includes the family, the animals, the garden, the reading, all that, but a primary focus on the partnership.”

Life stories are recorded in the crevices of my brain

and emotions bounce back from hollows in my body.

I am filled with the echoes of my loved ones.

(Echoes)

Ute interweaves among her themes of youth, love, and aging images of verdant forests, abundant flowers, and other nature scenes that give color and scents to her sentiments. The significance of the abundant nature imagery is echoed by her decisions on the title and the cover art (designed by Yellow Arrow Creative Director, Alexa Laharty). When asked, Ute explains that Listen came from a question when she was giving a reading for her last book, Gypsy Spirit. “One of the listeners said, ‘I read your book, and I am slow, is that a detriment?’ And I said, ‘No, on the contrary, if you’re attentive, if you’re reflective, if you listen, much more will come with a second reading.’ It’s ok to be slow and to reread and maybe pause at an image. Or reflect: What did you mean by this word when you could have used another one?” Furthermore, Ute says she has often used listening to nature as a way to heal.

“Go, and put your ear to the tree, which is [on] the cover [of the chapbook] and listen to what that tree has to tell you. What energy does it send to you? We have done it with the grandchildren very often. When I couldn’t solve [a problem] even with my hypnosis, I would say let’s go outside and you put your arms around the tree, and just listen very carefully. Because the tree maybe tells you something. Maybe a stomachache, and [my grandchildren] often would come back in and say, ‘It’s gone.’” Ute further expands that with nature we have a reciprocal relationship: “Many of my nature references are allegories. . . . In the story about my grandson hugging a tree when he had a stomachache, I tried to show that everything around us is alive and has its own energy. Our grandson could bring his discomfort to the tree and in turn receive solace. The book cover image has a different focus—listening instead of hugging. [Depicted on the cover is] a woman (or girl) [leaning] her ear against a tree. There is a symbiotic connection. She might feel the ‘Earth move under my feet’ as Carol King sings and the sun might touch her face or she might be listening to birds chirping, the wind whispering.” Ute emphasizes that art is symbolic of being able to pause and pay attention to the natural world around us.

. . . when light and warmth return with the dawn,

butterflies flutter about.

Nature thrives in abundance.

(Magical Greenery)

And it is not only with the title and cover art that Ute had very specific intentions. Everything she has done to have Listen come alive has been deliberate—even her decision to publish with Yellow Arrow. Ute expresses that when she was first introduced to Yellow Arrow, she saw the logo and immediately realized that it was the symbol associated with the Camino de Santiago that helps guide “the wanderers and seekers” along the way. Ute and her husband completed the pilgrimage in the late 1980s and soon discovered that Yellow Arrow’s founder, Gwen Van Velsor, had also taken a pilgrimage there. “So when I saw the yellow arrows coming from that old tradition it connected with me that the chapbook is also a pilgrimage. The poems are a pilgrimage from childhood to the dying and we stop along the way.” She continued to say that not only did Yellow Arrow’s connection to the Camino de Santiago solidify her decision to publish with us, but also its mission to emphasize women. “I love to comment on that because there are not that many journals that are geared toward women.” Ute further says that she has often heard of two main theories that women will follow about art: a theory by Virginia Wolfe and one from Anaïs Nin. “According to Wolfe, all art is gender-free. But I have chosen the other tradition: Nin. And [Nin] believes that art overlaps—men’s and women’s art overlaps, but men and women have a slightly different perspective on things. And, she said that women write with their blood. You dip your pen in your blood and you write with it. So, if you are of that tradition—as I am—you have a different perspective on the [Yellow Arrow Journal] and why it’s just for women. I want women to be aware of that tradition. And you do have to come in your mind to make a decision about which one you want to follow.”

By exchanging stories,

We can reach understanding.

(Talking and Listening)

*****

Every writer has a story to tell and every story is worth telling. Thank you, Ute and Siobhan, for such an insightful conversation and to Siobhan for sharing it. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

Grub Street: Inspiring All Kinds of Writers

Interviews from fall 2020

Yellow Arrow Publishing has had several interns from Towson University’s Grub Street, so we wanted to share more about Grub Street and Grub Street Literary Magazine. Grub Street and Yellow Arrow Publishing have a shared connection through a love of the arts, specifically literature. Our fall 2020 marketing intern, Elaine Batty, interviewed Gel Derossi and Grace Jordan, current Editors-in-Chief, to get a better insight into the creation of Grub Street. You can find the latest issue, Volume 70, on the Grub Street website. A huge thank you to Grub Street staff for working around their busy schedules to tell Elaine all about Grub Street.

EB: What is Grub Street and how does it work?

Grub Street is Towson’s student-produced, award-winning literary magazine that publishes editions annually. This year is the 70th edition of Grub Street. Edition 68 won a Gold Circle Award for the 17th year in a row that Grub Street has been recognized. Six students accepted in edition 68 were also recognized and awarded. Grub Street publishes a print edition each year, but we also run a website in which we feature more works from writers and artists. Students enroll in a year-long class under a faculty advisor—this year and in most previous years, our faculty advisor is Jeannie Vanasco—and through this class, students receive roles within top managing positions, genre teams, and marketing and publicity.

Grub Street accepts works submitted online in poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and visual art, as well as genre-defiant works. Anyone can submit to Grub Street, not just Towson University students. Our high school contest also features work from one to two high school students; all of our submissions are reviewed by an accomplished author—last year’s was Jung Yung, critically acclaimed author of Shelter—and winners receive a $100 dollar prize.

Our genre teams work together in reading submissions and deciding what works to feature in print and/or online. We also maintain a “blind review process” in which the top managing positions move over submissions from our Submittable account and remove any identifying information so that all works are chosen based on the works themselves; this levels the playing field and makes everything fair.

Putting together a literary magazine requires honesty from its staff. It requires clear communication and conversations about topics of personal and societal importance. With the way Vanasco facilitates our conversations about submissions and taste and aesthetics and oppression, [we] personally, and [we] sense others do as well, feel encouraged to speak up, even if [we] don’t speak perfectly and even if [we] might be wrong. Grub Street feels like a community. We talk to each other with what feels like an elevated form of respect. We honor the opinions of our classmates and [we] hope that everyone feels like every opinion of our staff is equally valuable. We all stand behind our mission of inclusivity and diversity and representation for marginalized identities.

EB: In what way do you feel Grub Street benefits Towson students as well as the community?

The ways in which Grub Street benefits students is vast: Grub Street gives undergraduate students the opportunity to get their hands into all types of work within the publishing and literary field. You don’t need prior experience to be involved in Grub Street, but you will leave with concrete experience within copyediting, reading submissions, marketing, [and] designing, and leave with a physical, new print edition of Grub Street that you and your team created together.

Grub Street also strives to engage within the Baltimore community. We distribute our print edition at book festivals, conferences, and other Baltimore-based universities, and are also working on distributing our issues to prisons.

Yellow Arrow’s Editor-in-Chief, Kapua Iao, also asked Brenna Ebner (fall 2020 publication intern and current CNF Managing Editor for Yellow Arrow, and Editor-in-Chief of Grub Street, volume 69) further questions about her experiences.

KCI: Where does the name ‘Grub Street’ come from?

It was originally an address in London back in the 18th century where low-end publishers and “hack writers” were found competing to make a living from their works. People there dealt with hard critiques, became targets of satire, and scuffled over plagiarism. Their literary world was cutthroat with aspiring writers constantly putting out new work to get noticed and no copyright laws to protect anyone’s writing. Our name commemorates that and the ways in which writing, publishing, and editing has evolved from that structure but still remains just as competitive and passionate. Dr. George Hahn, an English Professor and past chair of the Department of English, has a great explanation of Grub Street’s name included in each issue as well.

KCI: Can you explain more about how students get involved with Grub Street?

It’s a class at Towson actually! You can take it either first or second semester, but it typically is best to do both in order for sake of consistency in the magazine. If being on staff isn’t of interest to those who want to get involved, they can easily submit multiple pieces (there is of course a cap to the amount depending on the genre) and become a contributor. That option is available to everyone, too—not just students. Copies are free as well so if participating in those ways still aren’t of any interest, anyone could become a reader and supporter of Grub Street that way. We welcome everyone at the launch parties to celebrate with us (when they aren’t shut down for [COVID-19 regulations]) and to enjoy PDF copies online.

KCI: How does someone become Editor-in-Chief of Grub Street?

Recently it’s been . . . based on previous experience (have they taken Grub Street before?), performance as a student (good grades, attendance, etc.), and graduation date, which Vanasco, current faculty advisor, considers and then chooses based on that. The position requires you to be able to commit for the full school year, so we want someone that is reliable, committed, hardworking, and available. They’ll be in charge of the whole process: picking staff positions, making sure we stay on schedule, having final say on pieces we include and editing them, how the website is run, communicating between genre teams and the creative services department and faculty advisor, organizing the launch party, everything! The faculty advisor helps immensely though so it isn’t quite as overwhelming and the managing editors take on a large bulk of the process as well, such as the high school contest, weighing in on design and layout decisions, communication between staff, and much more. The whole staff is a strong support system but ultimately the Editor-in-Chief has to oversee it with the faculty advisor supervising and guiding.

KCI: What has your experience taught you?

Grub Street was what ultimately helped me figure out what I wanted to do in life after college. It gave me the direction and experience I needed to understand that editing and publishing was the career I wanted to pursue and could, and I can’t thank Vanasco enough for giving me that opportunity. I also don’t think anything could have prepared me for what to expect stepping into that kind of leadership role, too, but it helped me grow immensely on a professional level and taught me a great deal about myself. I never realized how much work went into publishing and editing until I got to be part of the process. When I pick up any piece of literature now, I think about all the people who put in the work to get it into my hands and in that polished state. For literary magazines and journals, specifically, I think about how between the covers is a space that has been created by multiple people for multiple people to express themselves and help them feel like they belong somewhere and to something. There’s a whole new appreciation for something I certainly took for granted previously and I want to continue to be a part of it.

Elaine Batty is a student at Towson University graduating with a BS in English on the literature track. Her poetry has been featured in the College of Southern Maryland’s Connections literary magazine. In her free time, she enjoys reading all genres of fiction, writing poetry, and playing with her two cats, Catlynn and Cleocatra. Elaine’s two real passions are literature and travel, and she plans to look for a job following graduation that will allow her to pursue both full time.

Gel Derossi (they/them) is a white, trans, neurodiverse person who reads, writes, and draws with a mission to create more representation for marginalized folks. They currently study creative writing at Towson University.

Brenna Ebner is a recent Towson University graduate and Editor-in-Chief of Grub Street Literary Magazine, volume 69. She has interned at both Mason Jar Press and Yellow Arrow Publishing and is looking forward to continuing to grow as an editor and establish herself in the publishing world.

Grace Jordan is one of the 2020–2021 Editors-in-Chief of Grub Street, along with [Gel]. She is a sophomore at Towson University, studying both Dance Performance and Choreography and English with a minor in creative writing. She is also a part of the Honors College. Find her on Instagram @graciejordan.

You can find Grub Street on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

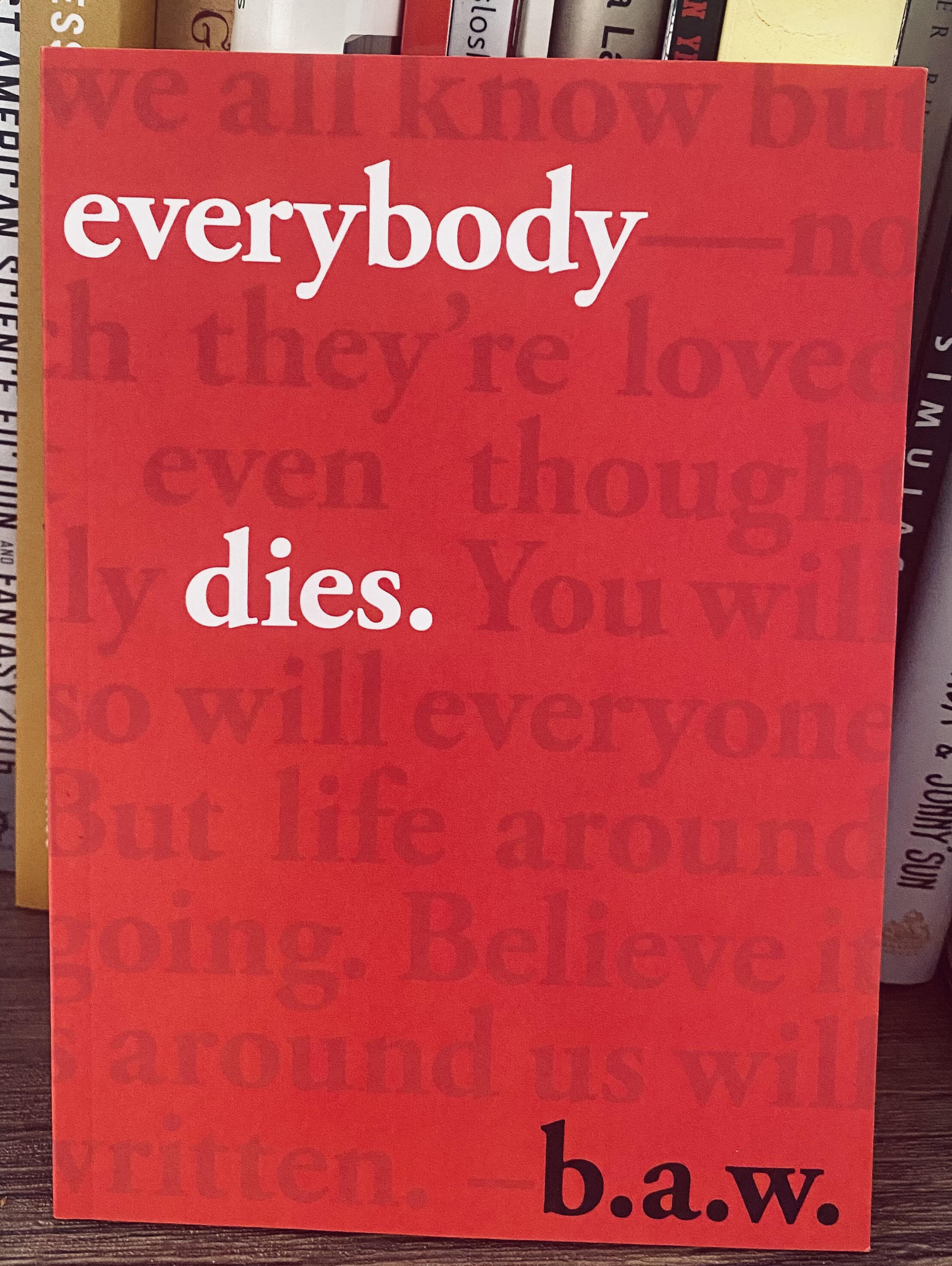

everybody dies. ~ A Conversation with Briana Wingate

Originally from December 2020

“I’m tellin’ you. Ain’t nothing a fierce woman has to say that goes unheard.”

From “In the Valley,” everybody dies. (2019)

A Yellow Arrow Publishing Editorial Associate, Bailey Drumm, interviewed author Briana Wingate about her 2019 book everybody dies. (currently sold out!). Briana Wingate (or b.a.w.) has recently decided to take ownership of her full name. She lives, writes, and socially distances in Baltimore, Maryland, with her lucky black cat and collection of adult coloring books. She finds inspiration in Black women, neo soul, and popular 90s television. When she’s not scribbling in a journal somewhere, she can be found curled up with a good book and a bottle of wine. She has very strong feelings about The Golden Girls and is willing to discuss them via Twitter or Instagram @briana_shmiana.

YAP: How was everybody dies. conceptualized?

Call it morbid, but I think a lot about death as just a part of the human process. It’s this one thing that we all do no matter who we are, who our loved ones are, or what’s going on around us. everybody dies. was basically my way of asking, “What if someone dies because that’s just what people do? What if the focus of the story was somewhere else?”

YAP: What is your routine writing practice like? Has it changed since this publication? If so, how?

It has! Believe it or not, I had more time to write while I was still in school, so it came a lot more freely. I didn’t have to think too hard about finding the time; I just did it. It was easy to make writing a priority in my life because there was so much outside motivation to just create, even when it didn’t come easy. Now, my motivation is mostly internal and always finds a way to fall in priority behind something else. It’s so much simpler to blame work and general adult life for not writing these days than it is to say I’m afraid of not being good enough at something that actually holds my heart. There was a period of time after completing the MFA program where I wasn’t writing at all, and it made me feel as though I was betraying myself. These days, I’ve been writing just for my own eyes, just to practice with no real expectations. When the stars align just right, I talk out ideas with friends as a sounding board. But I’m not ready to fully workshop what I have just yet, let alone submit. Almost, but not quite. It still feels a little uncomfortable sometimes. A little more hesitant. A lot more eraser smudges. But, I’ve been scribbling in my journal before bed each night, and it feels a little easier each time.

YAP: What was the easiest story to write?

“Things Falling from the Sky.” I had a lot of fun writing that one.

YAP: What about the most difficult? How did you tackle it?

“Dying Season” changed in so many ways so many times. Characters were swapped out, entire scenes were cut, and I was frustrated through it all. I had trouble getting to an ending that felt right. I can definitely say I leaned on my cohort a lot for help. But ultimately, I ended up walking away from the story for a couple weeks and going back over what inspired me to write it to begin with. A friend and I were talking and realized that someday, people who were part of such defining moments in our youth will eventually die without anyone calling to let us know. I found the ending when I realized that the feeling I was looking for was acceptance.

YAP: Were there any pieces that you considered for the collection that didn’t make the cut? Why?

Definitely. I had a two-page piece that I was certain was going to be the first story in the collection, but it just hadn’t been fleshed out enough in time for production deadlines. It’s still sitting in my files, so I may revisit it someday.

YAP: How did you land on this title? Were there any other contenders?

I don’t remember any others sticking with me as much as everybody dies. It’s something you can’t really argue with, but it’s still a conversation starter. There’s a death in each story, but each story is more about the surrounding events. By saying ‘everybody dies’ in lowercase letters upfront on the cover, it was like my way of saying, “Everybody dies. But that’s not always where the story is.”

YAP: I heard, when producing these, you had a handmade element. What was it?

I made a few handbound copies and tied live flowers to the front covers. Inside, I added sheets of vellum at the beginning of each story that were cut out to form an erasure poem from each first page.

YAP: What’s something you hope your readers get out of this collection?

A good laugh. A good hurt. A good conversation.

YAP: Do you have any new projects in the works?

[From March 2021:] I started a new podcast with a local visual artist/musician/good friend, Lové Iman. You can find us at ewwcreatives.com, follow us on Instagram and Twitter @EwwVarietyShow, and listen to The Eww Variety Show on all major platforms.

YAP: Is fiction the only form you practice?

Fiction is where my heart has always been, but I dabble in nonfiction as well. Nothing serious. Just my own long-winded introspections.

YAP: Would you choose to self-publish again in the future? What was that process like for you?

Who knows? I’d never say never, but there’s pros and cons to everything. I’m admittedly a control freak, so seeing something that was just mine go from concept to tangible object was definitely a rush. However, having worked behind the scenes with local presses before, helping other people see their work come to life, there’s definitely a level of comfort in knowing there are other people invested in your brainchild.

YAP: What do you hope people take from this chapbook?

Everybody dies. That’s not the whole story. How are you living?

YAP: How would you summarize this collection in less than 50 words?

everybody dies. is a collection of short stories that each include a dead body but aren’t about death. There’s a little bit of humor, a little bit of heartache, and a little bit of weird inside, all meant to tell the human story.

*****

Every writer has a story to tell and every story is worth telling. Thank you Briana for taking the time to share your stories with us. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

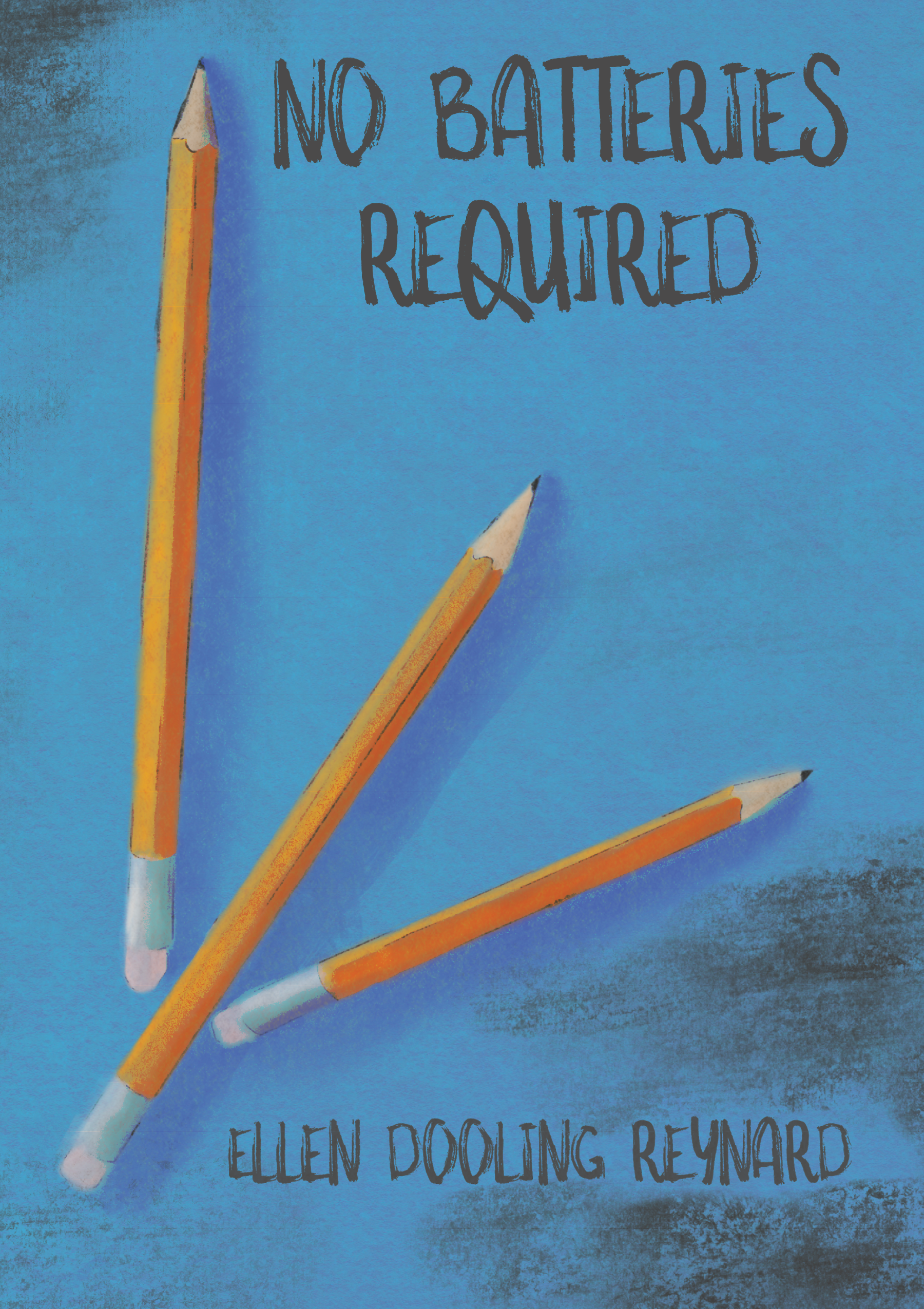

Cherishing the Present: A Conversation with Ellen Dooling Reynard

From February 2021

Ellen Dooling Reynard sits in her kitchen nestled in the foothills of the Sierra Mountains. Behind her, a black cat jumps onto the counter. She grins, “He wants to play with the keys.” Her warmth spills through the computer screen that connects us as Ellen mentions that he, along with her other cat, are sources of inspiration for her writing and laughter. Ellen, the author of the next Yellow Arrow Publishing chapbook, No Batteries Required, released April 2021, spoke to Yellow Arrow Editorial Associate, Siobhan McKenna, while taking a break from packing up her California home. This wonderful chapbook is now available for PRESALE. Information about a virtual reading at the end of April is forthcoming

No Batteries Required examines the world around Ellen from the perspective of her inner world. As a senior, she looks back on her life, its joys and sorrows, its loves and losses, while she navigates the unknown currents of old age and ponders about the journeys of life, death, and what lies beyond. Ellen spent her childhood on a cattle ranch in Jackson, Montana. Raised on myths and fairy tales, the sense of wonder has never left her. A one-time editor of Parabola Magazine, her poetry has been published by Lighten Up On Line, Current Magazine, Persimmon, Silver Blade, and The Muddy River Poetry Review. She is now retired and has relocated to Clarksville, Maryland, where she will continue to write fiction and poetry. She is currently working on a series of ekphrastic poems based on the work of her late husband, Paul Reynard (1927–2005).

In a week [from this interview], Ellen will be moving east to separate herself from the worsening wildfires and to be closer to family. Yet for someone who is moving across the country, she appears very at peace. “That’s life,” she says when asked how she is faring with the move. “Selling a house and packing a house and then dealing with something that’s wrong with the house. I can worry about all of that and then I realize that this is the second to last week that I’m going to be here—so that’s right now. What is going to happen is going to happen on the trip.” After a beat, she adds with a laugh, “I am a little nervous.” Siobhan asked Ellen to talk more about her appreciation for the mundane moments of life, her curiosity toward the natural world, and her ability to see aging as a gift—the themes of No Batteries Required.

YAP: The first section of your chapbook is called “moments and non moments” with even the non moments being full of meaning. How have you found your non moments to be “presents of presence”?

Because I’ve had a life-long spiritual direction that my mother was also involved in—the teachings of [G.I.] Gurdjieff . . . [a] middle eastern teacher of philosophy and knowledge. [His teaching] is a lot about being in the moment (before it [became] a buzzword in modern psychology) and living life right now; not yesterday and not tomorrow. What is in front of me right now? Who am I right now? These kinds of moments, the non moments, [are] what end up being “presents of presence.” [Presents of presence is about] finding yourself if you are really irritated because you are delayed by something. Maybe you are going to be late for an appointment. Or you may not even have a reason to be annoyed and you just don’t like slowing down. So, in the middle of a moment like that you have to realize that you are alive, and you are breathing and there are birds singing outside and interesting things to be feeling about one’s children and all of one’s loved ones. There is plenty of material in the present moment even if even if you are waiting at a broken traffic light.

YAP: How does it feel to look back at seemingly non moments: family breakfast, dishes, chores, Montana winters, and find meaning within them?

I learned deep down an appreciation for being where you are because we would be snowed in all winter. We were six children and my mother homeschooled us, because there was no way we could get anywhere. The nearest school was a [one-room schoolhouse in town], 10 miles away. We didn’t get down to town the whole winter. We would have to put away a lot of food and my mother had to figure out how to age the eggs in barrels. She had to cook and can, garden, milk cows, separate cream from milk, make butter . . . [having been gently raised back East, as a rancher’s wife], she learned how to do all that stuff—it was amazing.

YAP: Your second section called “Life’s Journey Home” centers on growing older. When referring to yourself in your bio you call yourself a “senior” and you call Fredrica a “senior” in the poem of the same name. Do you see yourself in Fredrica now as you have entered this older stage of life?

No, not Fredrica, but my mother and my aunt. My Aunt Peggy lived to be 103 and when she was in her 70s, she decided she was going to grow old gracefully. She was a very busy woman—did all kinds of project. . . . she kept chugging along all those years and always with a lot of laughter and a lot of good humor. And I’ve become the Aunt Peggy of my generation among my sisters’ children, and I don’t mind seeing myself that way. [Old age is] a kind of special time and a privileged time because you don’t have to prove anything anymore.

YAP: In “Old Age” you write, “these are the best years,” and talk about allowing the world’s youth to carry the burden of knowing “the unknowable” so you “old ones” can move “into a new world.” These words are beautiful and reminiscent of a future realm after this life. Paired with the title of this section, “Life’s Journey Home,” I’m curious as to what you believe our next life entails and if there is a spiritual aspect to your words?

There is a Native American belief that when you’re born you come through the Milky Way and there’s a person there called Blue Woman. [She] encourages the new life to go ahead and be born. Then, when somebody dies, they go back through the same portal and Blue Woman is there to welcome them back to the same world that they came from. That’s—in a way— my view: that after death of the body there’s some kind of life that goes on. It may not be angels with halos and sitting on white clouds, but there’s something that continues. . . . [Gurdjieff said] that depending on how we live there are various places where the spirit ends up. The ideal is to go back to the center of the universe—what you might call God; that original force that started everything.

YAP: In your poem “Montana,” I love the juxtaposition of the beauty of the natural world against the reality of the natural world. You talk about the mountains as “blue-shouldered and white peaked” but also “uncaring in their majesty” and the sun melting away snow that once again reveals the graves of your mom and your husband. Why are these contrasts important to you and how do you see the beauty and reality working together?

I think that was part of growing up on a ranch. Seeing a lot of birth and death juxtaposed with animals on the ranch. [We lived on] a cattle ranch so we saw animals being born and I was interested in one being butchered, but my mother didn’t want me to watch. My father also had a very beloved dog who was a wonderful cow dog. My father accidentally killed him when he was backing up some huge machines and [ran over] the dog. . . . I saw a lot of extreme opposites in relation to nature. I think it happens within human beings also—there’s joy and there’s sorrow and they define each other.

YAP: Your final section is called “Seasoned with Humor.” How are you able to find humor within the trials of getting older?

I think my Aunt Peggy, who was a big influence in my life, was the one with the best sense of humor. . . . I went through a period of life where I was a sad person and being around my aunt was always a big help. Even when things were really hard, she had a sense of humor. At one point for instance, she fell and broke her back in her 90s, so she had to be in her room for a long time on a hospital bed. She asked if they could push her hospital bed around so she could look out the window because there was a squirrel feeder. There was one squirrel that would do all of this crazy stuff, and she would sit there and laugh—with a broken back. She was no sissy.

Also, with aging, I am lightening up. I don’t know exactly why. Because when you’re young and busy with a career and having children—there’s a lot that makes you go like this *Ellen furrows her brow and points to the space between her eyebrows* and it makes you get this crease. [With age] it seems more possible to just relax in front of something that is difficult. They say that things don’t hurt so much when you relax. It is when you tense that you make all your nerves jangle and relaxing feels better.

YAP: How long have you been writing?

I’ve been writing various things for a long time. I was an editor, and I wrote some [articles] for the magazine I was working for which was Parabola Magazine. I only started writing poetry a little more than a year ago. I took a memoir class and started to privately publish for my children the story of my life and their life. My [memoir] teacher was really good, and I found out that she was going to be teaching a poetry class at the local OLLI Institute—the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (it’s a non-for profit that makes it possible to have classes for senior citizens at very little cost). Anyway, [my teacher] was going to give a poetry class so I thought well, let me try writing poetry. [My teacher] was very encouraging and we became very good friends. Eventually, one thing led to another and she actually proofread this manuscript for me. Because of the classes, I’ve [joined] some writers groups mostly for people like me—not so young. It’s been very inspiring. I love it.

YAP: What does having your poems published for others to read mean to you?

It’s a real shot in the arm. I just started writing poetry and already to have something that other people can read; I love it. It really inspires me to keep on going and keep on writing.

YAP: What was the inspiration behind the cover with three pencils?

I was just fooling around with my camera, and I [visualized] pictures of pencils. I got different pencils and lined them up in different ways. And then, [Kapua Iao, Editor-in-Chief] got [Yellow Arrow’s Creative Director, Alexa Laharty] to draw it and I really loved it. It was just a little visual moment that I was having with my pencils and my camera—I was just doodling around. I’m so glad [they] wanted to run with that idea.

YAP: Why did you decide to publish your work with YAP?

Because you accepted me! I sent it out to lots of different places and didn’t get any other offers. I’m thrilled. I also noticed that [Yellow Arrow had] lots of workshops and events so I’m hoping that once we are allowed to go out and meet people that I would love to find some writing groups!

*****

Every writer has a story to tell and every story is worth telling. Thank you Ellen and Siobhan for such an insightful conversation. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

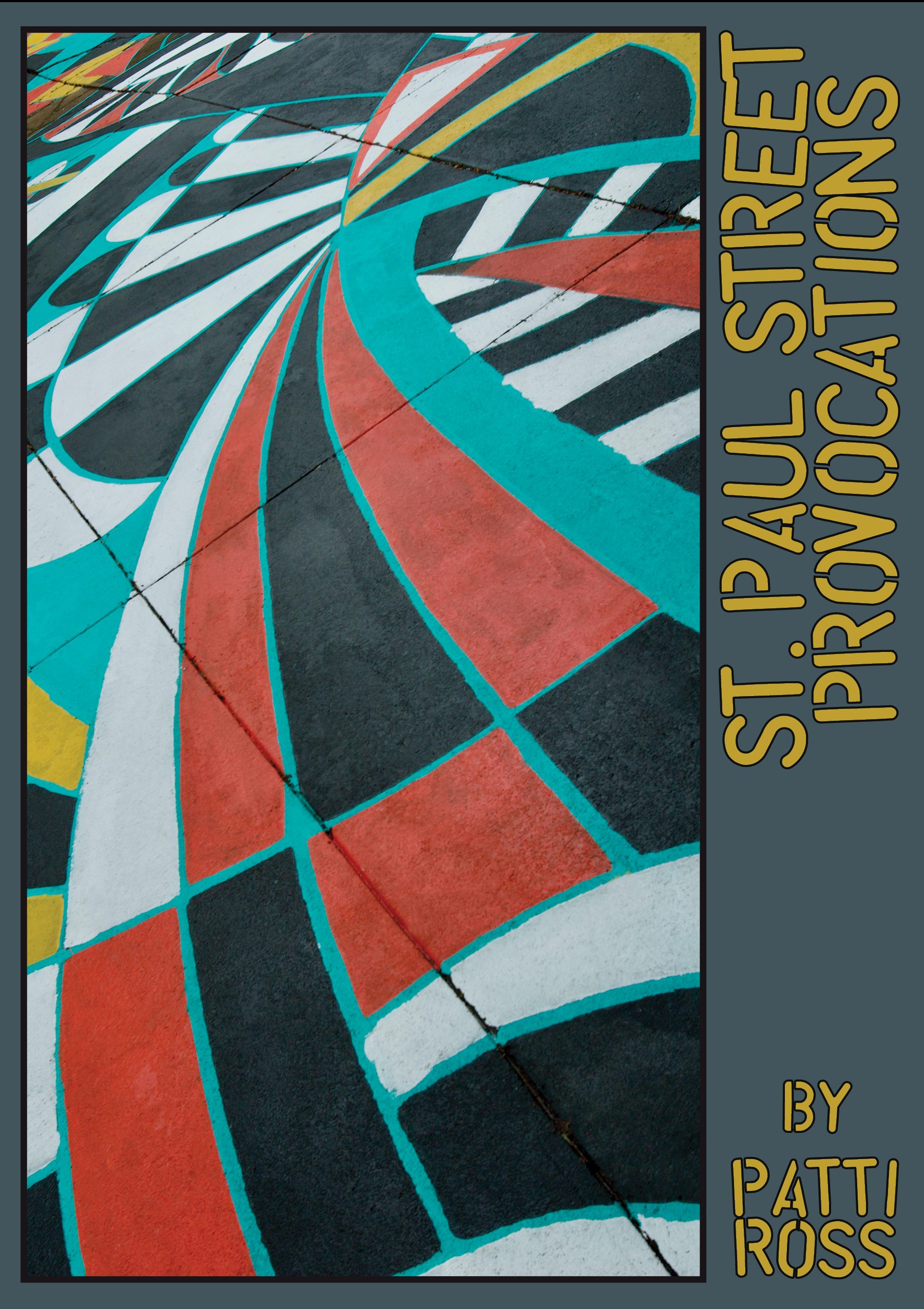

Evoking Provocations from Patti Ross: A Conversation

Overwhelmed by the gentrification occurring from 2010 to 2013 in the areas around North Avenue and St. Paul Street in Baltimore, Maryland, Patti Ross recognized that the people from the neighborhood were being slighted by their own city. While the tenants preached their woes of displacement and fear of homelessness, Patti listened, wrote, and became an activist for their concerns in order to let them be heard. From this, St. Paul Street Provocations, Patti’s debut chapbook with Yellow Arrow Publishing, now available for PRESALE and ready for release in July 2021, was born.

Patti Ross graduated from Washington, D.C.’s Duke Ellington School for the Performing Arts and The American University. After graduation, several of her journalist pieces were published in the Washington Times and the Rural America newspapers. Retiring from a career in technology, Patti has rediscovered her love of writing and shares her voice as the spoken-word artist “little pi.” Her poems are published in the Pen In Hand Journal, PoetryXHunger website, and Oyster River Pages: Composite Dreams Issue, among others. You can find Patti at littlepisuniverse.com or on Facebook and Instagram.

A Yellow Arrow editorial associate, Bailey Drumm, recently interviewed Patti about her upcoming chapbook and what her home on St. Paul Street meant (and means) to her. You can also hear more about St. Paul Street Provocations and Patti tonight (February 9) at 7:00 p.m. with the Wilde Reading Series, also featuring Yellow Arrow’s very own Gwen Van Velsor.

YAP: What was the catalyst for the creation of St. Paul Street Provocations?

I am an advocate for the homeless and marginalized. I have long considered myself an advocate and am a member of the Poor People’s Campaign. I wanted some of those [people] that I met when I lived one block off North Avenue, in a somewhat blighted neighborhood, [I wanted their] voices to be heard, for them to be seen in some way—recognized. When I would chat with my homeless or economically and mentally challenged friends, they would all reveal a feeling of invisibility to society’s majority class.

YAP: What does Baltimore, especially St. Paul Street, mean to you?

Baltimore is my adopted city. Once I learned its history—I understood it better. I understood why there were streets that appear to be allies. I understood what Penn Ave and North Ave meant to the community. St. Paul Street and its community allowed me to rediscover and shape who I am. I often go back to the area and just sit and reflect. I can see evolution and the lack of progress at the same time. There is romance there for me.

YAP: This collection seems incredibly personal, genuine, and emotion-provoking. How would you describe the feeling of seeing the pieces put together in one place?

It is exciting and surrendering at the same time. The collection is very personal. Most of the poems were written out of experience—either my own sights or the stories of others.

YAP: Why ‘Provocations,’ specifically? What does that word mean to you in the context of the title?

[Provocations] is important in the title because the poems are about frustrations, irritations. The poems speak to injustices and the affronts that those who are marginalized deal with daily.

YAP: Along with writing, I hear you are part of the spoken-word community, sharing your voice as the spoken-word artist “little pi.” How did you originally get involved with the spoken-word community?

I just jumped in. I went to the high school of performing arts in D.C., so I have known about performance poetry for quite some time. However, when I moved to Baltimore, I was looking for a way to share my thoughts and I started attending open mics. I was too scared to read at the time—I think I let my [age], being much older than those on stage, create a lack of confidence. Once I moved back to Ellicott City, an area I had lived for over 15 years, I felt comfortable performing and reading in front of an audience. Root Studio owned by Karen Isailovic was my first stage, and they held an open mic every Friday, so I started there. Once I built up my confidence I started going to Red Emma’s and that is where I saw and communed with some phenomenal slam champions and spoken-word artists.

YAP: How has spoken word helped you creatively, therapeutically, etc.?

Creatively it has helped [me] to discover and define my public persona. I am clear on what I want to advocate for and who. I also see it as a path to advocate and remind society of those on the fringes. Therapeutically? I’m glad you asked this. I get so much joy out of not just presenting my work but listening and sharing the work of others. I believe in a higher power and the stars of the universe. I think much of what we do as individuals is kismet.

YAP: What would you consider to be the heart or heat of this chapbook?

It is all about recognition of what is happening in the streets or our cities and the things we choose to ignore. It is about a haunting that we need to rectify. For example, the poem “Indemnity,” or sometimes I call it “Football,” is all about remuneration. In that poem, the idea of a football game—played by men whose ancestors fought in the Civil War and by men whose ancestors were former slaves prior to that war—the lineage of one group can be easily dismissed. In “Ghosting” families of color have accepted permanent separation for hopes of heritable betterment, right? Slave families were forcibly separated for the betterment of the slave owner and here we have post-slavery families willingly separating themselves.

YAP: Was there any particular piece that was hard to tackle and get to its final form?

“History Month” was tough. I was trying to say a lot in that piece, and I had a hard time finding a way to get it all in without sound preachy. I also understand the need for the naming of the month, but I do not like it. I would prefer the history of this country be told correctly without the revisions. I had conversations with elders who understood what I was saying but did not agree that the recognition month should be eliminated.

YAP: What does the featured mural (on the cover) mean to you, and to this collection? Were there any particular emotions it evoked, or direction of words it inspired?

The mural is the creation of Jessie Unterhalter and Katey Truhn of jessie and katey; they are Baltimore-based muralists. They created the mural on the grounds of the dilapidated park across the street from my former apartment. (A side story is someone [once] planted rose bushes in the park and nurtured them until they grew beautiful blooms. I never saw anyone doing the work, but one day the roses were all in bloom and the park looked beautiful even with the trash and drug needles strewn between the grasses. The very next day, sometime in the early morning, when we woke up, the heads or blooms of all the bushes had been cut off and left on the ground. It was a sad and frightening sight.) I watched them daily create something beautiful out of something blighted. The mural is called “Walk the Line,” and in that neighborhood at that time, you very much had to walk a certain line. You had to be an insider. You had to know your way around. For me, the mural evoked a way out of whatever situation you [might] find yourself in.

YAP: Will you be including any other artwork of your own in the collection? If so, is it inspired by any particular poem or the collection as a whole?

I hope to have at least one piece of my artwork in the book and it is a bleeding or beating heart. In honor of George Perry Floyd, Jr.

YAP: Why did you choose Yellow Arrow to publish St. Paul Street Provocations?

I love the concept of a woman[-run] publishing company. As a feminist, I am always seeking opportunities to collaborate with like minds. I was elated when they decided to publish the book. I had been trying to figure out a home for the collection. In many ways, I had shifted in my writing, but the experiences still clung to me and I needed to find a place for the words to rest. I will never stop performing the poems until the injustices are corrected.