Yellow Arrow Publishing Blog

My Top 12 Books of 2023 to Read from Natasha Saar

By Natasha Saar

With March coming to a close, there’s still plenty of time for you to spend reading, reading, reading. If you can tear your eyes away from Yellow Arrow Publishing’s work, I've compiled a list of 2023 must-read books that might tickle a similar reading itch . . . and you’ll get to see what everyone’s reading nowadays.

1. Good for a Girl by Lauren Fleshmen (Penguin Press, get your copy here)

In this half-memoir, half-manifesto, Lauren Fleshmen tackles the world of running and commercialized sporting from its greatest highs to its greatest lows—and there are much more of the latter. Fleshmen gives voice to girls fitting into a sporting system designed to lift men and, with someone with her multitude of experience, she has a lot of it.

2. Yellowface by R.F. Kuang (Harper Collins, out in May, get your copy here)

After the death of fellow student and literary superstar Athena Liu, fame-hungry Jane Hayward is hit with an idea: steal Athena’s manuscript and pass it off as her own. So, what if it’s about Chinese laborers under the British and French in World War I? Even if Jane’s not from Athena’s exact background, shouldn’t this story get told? Reviewers seem to agree, but critics seem convinced there’s something Hayward isn’t telling them. . .

3. Age of Vice by Deepti Kapoor (Riverhead Books, get your copy here)

Sunny’s the lady-killer heir, Ajay’s the family maid, and Neda’s the plucky journalist. Their one similarity: a connection to the Mercedes that jumped the curb, killed five, and left one baffled servant. Now, they’re caught in a plot that spans towns, families, friendships, and romances, and you’d better hope it ends with them keeping their heads. It’s the Indian mystery thriller you always knew you wanted!

4. A House with Good Bones by T. Kingfisher (Nightfire, get your copy here)

If you’re like this blogger, you like a good Southern gothic—and if you’re not like this blogger, you might still want to give this one a look. After accepting an extended visit home, Sam discovers a house quieter, dustier, and emptier than she remembered. With her Mom’s trembling hands and the vultures circling overhead, Sam feels like there’s anything but a good omen rising.

5. Old Babes in the Wood: Stories by Margaret Atwood (Doubleday, get your copy here)

Margaret Atwood returns to short fiction for the first time since 2014 with a series of tales that depict a mother-daughter relationship. The twist? The mother purports to be a witch. It’s a bunch of bite-sized glimpses into what family means when it’s held down by baggage, fantasy, and complications.

6. Happy Place by Emily Henry (Berkley, get your copy here)

If you’re into some contemporary chick lit, Emily Henry has delivered yet again. This time, the package is in the form of a college romance, an annual getaway, and a breakup. Except this breakup happened six months ago, and they haven’t told their friends. Not wanting to ruin their yearly vacation, Harriet and Wyn agree to pretend to be a couple for one more week . . . but will the facade break, or stop being one at all? (Knowing the genre, probably the latter.)

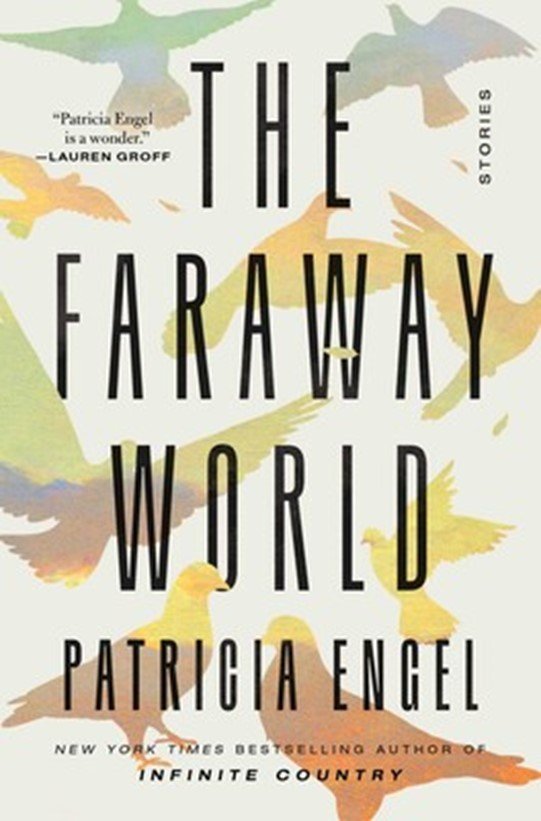

7. The Faraway World: Stories by Patricia Engel (Avid Reader Press, get your copy here)

Engel takes us on a journey of Latin America's communities burdened by poverty, family, and grief, and there are a lot of them to be had. This compilation of 10 (previously published) short stories will give you a taste of the full breadth of human experiences with an authentic voice, witty writing, and vulnerability that will touch anyone.

8. My Last Innocent Year by Daisy Alpert Florin (Henry Holt, get your copy here)

Isabel Rosen is part of the prestigious elite, about to graduate into eliter, and has always felt out of place. After a nonconsensual encounter with one of the only other Jewish students on campus, she’s about to feel that even worse. A whirlwind affair with her older, married writing professor is the only thing she has to cope, but nothing about it seems to bode well for her.

9. Really Good, Actually by Monica Heise (William Morrow, get your copy here)

Maggie’s got it all: a dead-end thesis, a dead-end marriage, dead-end savings, and she’s not even 30. With her support group by her side, Maggie barrels through her first year newly single with wit, humor, and heavy self-deprecation. Emphasis on all three, and additional emphasis on it being a wild ride.

10. The Mostly True Story of Tanner and Louise by Colleen Oakley (Berkley, get your copy here)

Tanner’s chance to escape a life made up of 19 hours of video games comes with an opportunity to be an elderly woman’s live-in caregiver. Simple, except for the fact that Louise didn’t want a caretaker in the first place, looks weirdly similar to a prolific jewelry thief, and, one day, insists that they leave town immediately. Thus ensues a wacky road trip that spawns an equally wacky—and unlikely—friendship.

11. Wolfish: Wolf, Self, and the Stories We Tell About Fear by Erica Berry (Flatiron Books, get your copy here)

Erica Berry has walked a years-long quest to study the cultural legacy of the wolf, and this is the result. If you’re interested in wolves, this will tell you all you need to know. If you’re not, you can find criticism, journalism, and memoirs galore that let us peer into the world of predator and prey. What does it mean when we, as humans, can be both?

12. I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai (Viking, get your copy here)

Bodie’s ready to leave her past behind her, but she can’t resist her ala mater inviting her back to campus to teach a course. That just means she’s back to thinking about her college roommate’s grisly murder, and how strange the conviction was, and how she has this nagging feeling that, back in 1995, she might’ve known the key to solving the case. But is it too late to run it back?

Have you read any of these already? Did I miss a few most-definitely, absolutely-necessary mentions? Tell us about it in a comment so that we can pick up a copy today.

Natasha Saar (she/her) is a senior at Loyola University Maryland, pursuing a BA in English, and the spring 2023 publications intern at Yellow Arrow Publishing. She’s in charge of editing nonfiction submissions at her university’s literary magazine, Corridors, and also works as a resident assistant in her dorm hall. In her free time, she enjoys folding origami, baking, and playing social deduction games.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we SPARK and sparkle this year: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

A Week as a Publications Intern

By Jackie Alvarez-Hernandez, written November 2022

When I was little, I adored the idea of being surrounded by books. In my head, my ideal world was one where I could spend every second of every day in the library, helping people find whichever story they wanted. And I could help people write stories and put them there in that library for others to find.

Obviously, this didn’t come to pass. Being a librarian takes a lot more work than my younger self imagined, and I had no idea of what went on in book publishing. But that desire to help people with their stories is something that’s remained the same. So when Yellow Arrow Publishing opened applications for an internship as a publications intern in the fall, I knew I had to take the chance.

I wasn’t sure what to expect, truly. I didn’t know how involved I would be—I had an internship in publishing beforehand, but that was in a different place. How many of the rules would be the same? How much would be different? It’s a common question everyone wonders when going somewhere new.

As it turns out, there’s a lot to do.

I usually start my week by looking at the schedule outlined for me by my supervisor, Kapua Iao (who is amazing and is always ready to answer my many, many questions), the editor-in-chief. The tasks can range from large to small, mainly projects that involve promoting or working on Yellow Arrow’s publications, both old and new.

For instance, I’m often tasked to read one of the chapbooks Yellow Arrow has published in the past or one of the previous issues of Yellow Arrow Journal. From there, I pick out five quotes from the pieces within and create promotional images for them on Canva to later publish on our social media accounts. This one is actually pretty fun to do—not only do I get to read some incredible poetry and creative nonfiction, but I also get to come up with images that represent the quote I selected. It can get very creative!

I also work on creating social media posts to celebrate certain holidays with a Yellow Arrow twist. This means crafting a promotional image on Canva, coming up with a fitting text description, and creating relevant hashtags for our Instagram posts. One of my first tasks had been to put together the black-and-white collage of the board and staff of Yellow Arrow for Women’s Business Day. I also worked on Black Poetry Day, sending an email to some of our African American poets beforehand and then organizing their answers for a post. I even put together the weekly posts for National Book Month 2022 and for NaNoWriMo 2022!

I’m also in charge of updating the blog posts for Her View Friday. This one requires some diligence, given that sometimes we receive some late submissions at the last second. Often the schedule will mention checking and double-checking the submissions list before the blog gets posted. Once the post is made, I’ll head over to Meta Business Suite and schedule the social media posts that will announce the new blog post.

Of course, it’s not all just social media. One big task that I’ve been helping with over numerous weeks is the next issue of Yellow Arrow Journal—in my case, it’s Vol. VII, No. 2, PEREGRINE. This involves voting on which submissions we should include as well as copyediting some of the pieces we chose. I’ve also helped proofread the issue to find any missed mistakes. Since we’re trying to get this published by November 22, keeping to deadlines is a must. Often, I’ve had to set aside some extra hours to have everything checked over and ready in time.

Sometimes I also assist with promoting new chapbooks we’re releasing, like putting together an email template before sending it off to bookstores on our mailing list (and really, sending an email should never be so nerve-wracking).

Other than these big tasks, I often get assigned some smaller ones that vary with each week. Sometimes it can be organizing the blog calendar, preparing it for next year. Or it can be updating our author list with their social media tags. (You know, the usual busy work that needs to get done.)

And then of course, sometimes I’m asked to write a blog post. Don’t worry, I do get to pick a topic ahead of time and schedule a date that I can finish it. Reasonably, of course.

It seems like a lot—and it is. This along with my schoolwork is not something simple.

But it’s worth it. I can say that everything I’ve done has helped me understand what goes on in book publishing, both online and in the real world. We do so much just to get our authors seen and heard. Obviously, I didn’t apply thinking it’d be easy.

But I also didn’t think it’d be this fulfilling. Seems like that’s one thing about books my younger self got right.

Jaqueline Alvarez-Hernandez (or just Jackie) (she/her) was born and raised in Frederick, Maryland, and just graduated from Loyola University Maryland with a bachelor’s degree in writing. A fan of stories whether on the page or on the movie screen, she hopes to start a career in book publishing that will allow her to explore any and all types of writing. She loves to read and write short stories in both fantasy and horror genres. In her free time, she enjoys spending time with her family and playing video games with her fiance. You can find her on Facebook @jackie.alvarezhernandez.77 or on Instagram @honestlytrue16.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we SPARK and sparkle this year: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

A Heart’s Deepest Desire

“The key to finding happiness in this life is realizing that the only way to overcome is to transcend; to find happiness in the simple pleasures, to master the art of just being. The things you love about others are the things you love about yourself.”

~ Brianna Wiest (Instagram @briannawiest)

By Amanda Baker, written November 2022

I’m going to tell you something that you may not expect: you do not know what you want. When it comes down to truths, you likely do not fully know your heart’s deepest desire. You may think you want a fancy home, a high paying job, to be “chief of something,” to get a brand-new car, etc. But these are not your deepest desires.

Your deepest heart’s desires are buried under years and years of conditioning, learned beliefs, ego-driven satisfaction (some of these wants are really great, and they really may serve you and move you toward your truest, deepest desire). In Sanskrit the word sankulpa translates to “intention” or “to become one with.” And we can use our intentions to connect with our deepest heart’s desire. Moreover, what we believe we want can help us connect with what we truly desire, in a spontaneous and even symbolic way. It’s once you start to open it little by little that the magic happens. You can’t chase it like we are led to believe. Your deepest desires come to you.

Me, I’ve always wanted to feel whole, to be significant, to be remembered. But, I never wanted to be a poet, never dreamed of being a yoga instructor or using the therapeutic philosophy of yoga to treat my clients as a mental health therapist. Somehow, individual yoga-based therapy stumbled upon me when I was given referrals from an old supervisor. People in my yoga classes started asking for therapy yoga sessions. My business built itself, and I believe it’s because I did not fully seek it, obsess over it, or hustle for it.

I had wanted to be a mental health therapist since I was 18 years old. I followed the blueprint of “get my diploma, go to a reputable college, get my master’s in clinical social work,” and wa-la, I made it! I had a series of stable jobs, won some awards, and believe me, those things were gratifying. Connecting with young children, eventually adults, and being a catalyst for their happiness allowed for some really amazing moments. I also married my high school sweetheart, bought a home, and had a child; we were living the American Dream. So why did I continue to have a long-standing emptiness in me? This longing for something more? It stayed with me everywhere.

I never imagined that I could be a yoga instructor because in my mind, I am terrified of public speaking. My heart, though, knows that I am destined to share publicly in some way. I spontaneously signed up for 200-hour yoga teacher training in 2019 and from there my heart truly started to learn how to open.

Then, it was through yoga and fears of rejection, actual rejection, loss, and heartbreak that I returned to writing. Even though I never wanted to be a poet, repeating patterns in my life brought me back to what I loved to do at age seven: write poetry. I followed a yearning, I did not know was there, to self-publish old poems and to continue daily to write new ones. And here’s what I found out, sharing my poetry has lived in my heart’s desire since I was a child. I even call it an epiphany to go to my childhood home and read through my old diaries and journals. Now, it is through my prose poetry that I share deepest truths and connect, even resonate, in such an intimate way with others.

What you obsess over is not what you truly desire / it’s something that will get you close to safety / likely temporarily / then that will likely turn dull / boring / maybe even unsafe / and it’s because those things are external / safety is an internal state / sometimes fostered by an external anchor / maybe another person / a sensory experience / an expressive catalyst / like writing / music / or genuine authentic shared connection.

You have to open your heart / and you can only do that when you feel really, really safe / and the reality is / most of us don’t.

I hope you find safety / I hope you connect / I hope you come to understand your deepest heart's desire when it shows up at your feet or right in front of your face / and when it’s there / I hope you accept it.

Poetry is one way I open my heart and stay true to myself. Here are some suggestions for you:

Meditate for three to five minutes then engage in a “brain dump”: stream of consciousness writing; write whatever comes.

Set a sankulpa or “intention” for your day. State it as if it already happening: “I trust my inner wisdom.”

Practice restorative or gentle yoga with a focus on the heart chakra.

Do a loving-kindness meditation, a radical act of self-love and healing. “mindful: healthy mind, health life” and Jon Kabat-Zinn provide a great loving-kindness meditation (including audio!) at mindful.org/this-loving-kindness-meditation-is-a-radical-act-of-love.

Exercise self-compassion, for example, see Tara Brach’s RAIN technique at tarabrach.com/wp-content/uploads/pdf/RAIN-of-Self-Compassion2.pdf.

Write a love letter to yourself

Read creative nonfiction books by Brianna Wiest such as The Mountain is You and 101 Essays that Will Change the Way You Think.

So, all in all, when you open your heart, your deepest desires come to you. You will know when you feel it. My heart’s deepest desire is to connect with your heart’s deepest desire and bring it to life.

I write to remember

I write to forget

I write to elicit freedom

And rid regret

I write until it’s exhausted

Collecting negative unconscious

I write.

And so can you.

Amanda Baker believes that we are more authentic as our childlike selves than we are as adults. We are more likely to share our truth and live our truth as children, but who says we have to stop. Amanda is a mental health therapist, 200-hour yoga instructor, and poet from Baltimore, Maryland. She attended the University of Maryland School of Social Work and James Madison University. She is a mother of her four-year-old son, Dylan, and enjoys time in nature. Amanda has self-published a poetry collection that includes written work from her early teens into her 30s. You may find her book ASK: A Collection of Poetry, Lyrics, and Words on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Her chapbook What is Another Word for Intimacy? was released October 2022.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. You can support us as we SPARK and sparkle this year: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 65185, Baltimore, Maryland 21209). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Fifteen Seconds in the Woods

By Beck Snyder, written September 2022

I am walking toward the forest in the middle of a chilly November night. Gravel crunches underneath my foot, completely unseen, and the path ahead is lit only by the small flashlight my phone provides. The light lets me catch a glimpse of the rundown white barn I’m passing, one that is hopefully empty, and I am beginning to wonder if having the flashlight on is worse.

Here’s the thing about me—I have a lot of bad ideas, and most of the time, I’m stubborn enough to go through with them.

Having a creative mind does that to you, I think, especially when given a prompt. Mine was simple: go to a location, take that location in, and write about it. Then, go to the same location when something was different (time, weather, amount of people there, etc.) and write about it from that new perspective.

That prompt and a few rejected ideas later led me to now, walking out towards Fairview Mountain past midnight, armed with nothing more than a flashlight, a journal, and a pen to jot down any notes. A terrible idea? Yes. Obviously. Anyone who’s seen more than 30 seconds of a horror movie could tell you that much, but I’d already been up on one of the mountain’s hiking trails earlier that week with the very same notebook and pen in hand, and as the sun shone above me, I’d felt more relaxed than I had since I headed off to the figurative mountain of work college laid out before me. How much different could the experience be at night, especially if I was bringing along a light source of my own?

Very.

The path continues past the barn, gravel and pavement giving way to packed dirt and grass that was just tall enough to need to be mowed again. I am relatively safe for the moment, with most of the forest still a fair distance away as I make my way through the meadow that sits next to a fishing lake. Claustrophobia has yet to set in, but I can still hear the chirping of nearby, unseen crickets, and a faint buzzing noise that reminds me of cicadas, but it’s far past their season. When I came here during the day, the tweeting of birds and buzzing of insects was a reminder of life, of how much this forest sustained. Now, it only sends a chill through my bones as I am reminded of just how many creatures are around that are beyond my sight.

But I am determined to continue. It is one of the few times my stubbornness has outweighed my anxiety—though, I suppose, my anxiety had a hand in keeping me moving forward. This writing prompt is one for a creative nonfiction class, one taught by my favorite professor, a man we all call Ben. The first time I was in his class, he told me he was impressed by my work. I don’t want to let him down.

I press on past the lake. It’s a cloudy night out tonight, and there is no reflection of the moon within the still, silent water. There is only my flashlight to illuminate it, and the stillness feels uncomfortable. People come up to fish on this lake constantly. There’s supposed to be something alive in there, but not even the reeds sprouting up along the edges are moving. The air itself is dead around me and trying not to think about it only makes it all the more noticeable.

I move on. Just past the lake and the meadow lies the final sign of civilization before plunging into the depths—the road that leads further up the mountain to the Outdoor School. I walked up this road once in fifth grade, followed by a pack of other fifth graders dragging duffle bags behind them, ready to spend our first full week away from home learning about identifying plants, going on hikes, and playing games about the food chain. As I continue along it, I catch sight of the pavilion where we played Predator/Prey, in which I was given the role of omnivore. I still remember the exact bush I was trying to hide behind before I was spotted, my hiding place announced to the enemy carnivores by Hunter, who ironically, was an herbivore. I can spot it now, just barely illuminated by one of the flickering street lamps.

I stop for a moment underneath that same street lamp. I’m not sure what stops me here—maybe I’m clinging to the last beam of light I’ll have before I am left alone with only my flashlight. Maybe I want to stay in the familiarity, here outside of the pavilion where I lost a game I was determined to win, all because I’d worn snow boots that I couldn’t run in. Perhaps I should have chosen this spot for my prompt. It’s more open and illuminated, has more memories tied to it—

But I didn’t choose this place. I chose to walk down the hiking trail into the forest for a more authentic prompt, one in which I had no previous memories, and at this moment, as I stare down at the little wooden arrow sign painted dark red pointing down the trail, I can’t remember why.

Ben, I think, as I suck in a terrified breath. I cannot disappoint Ben.

I start down the trail. The light from the street lamps behind me quickly disappears, covered up by the countless tree trunks and branches that seem to close in behind me. Fallen autumn leaves crunch under my feet, and while the noise gives me joy in the daylight, now it makes me cringe. I do not want to be heard. Not by whatever creature could be lurking just outside of my flashlight’s beam.

My mind, of course, is no help. A few of the tree trunks have hastily spray-painted circles and arrows decorating their trunks. They are meant to be guides, a sign that you are headed down the right path, markers to show where you’re going and where you’ve been. In the darkness of night with no moon overhead and only a flashlight, however, my brain has not-so-helpfully dragged forward memories of horror stories that kept me awake at night in middle school and suddenly reminded me of just how similar my current situation is to Slenderman.

I speed up. My spot is about a five-minute walk down the path at a casual stroll, I make it there in half the time, my breathing just as quick, and after an extra 30 seconds of deliberation, make up my mind and switch the flashlight off. It is worse, I think, if I were to turn around and see something than it would be to sit in pitch-black darkness and hope nothing is there. Ignorance is bliss and all that.

Last time, in the sun, I sat out here for 30 minutes. This time, my heart pounding in my chest as the darkness seems to constrict around me, I decide I will force myself to sit still for 30 seconds. I will sit here, listen to the sound of distant bugs and bats that I will not see, feel the cool, still air against my arms, and collect just enough information to write about it.

One . . . two . . . three . . . four . . .

I’m calming down, the longer my timer goes on inside my head and nothing terrible happens. No supernatural creature is lurking behind one of the tree trunks to kill me. It is simply me, the crickets, and the moonless sky. There is something almost beautiful about being entirely alone like this on a night as close to silent as the forest can get. It feels as if I am the last human on Earth—

A twig snaps on 15.

My stubbornness finally loses the fight, and I bolt. I tear back through the hiking trail, down along the road, past the lake, and across the meadow as fast as my legs will carry me. I do not stop until I am past the old white barn, and there, I double over to gasp for air, my lungs heaving as exhaustion takes over from adrenaline.

I am left with one comfort: those 15 seconds will be enough to write a complete prompt.

Beck Snyder is a senior at Towson University studying both creative writing and film. They are from the tiny town of Clear Spring, Maryland, and while they enjoy small-town life, they cannot wait to get out of town and see what the world has to offer. They hope to graduate by the summer of 2023 and begin exploring immediately afterward. You can find more from Beck at their Instagram @real_possiblyawesome.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. We recently revamped and restructured its Yellow Arrow Journal subscription plan to include two levels. Do you think you are an Avid Reader or a Literary Lover? Find out more about the discounts and goodies involved at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/yellow-arrow-journal-subscription.

You can support us as weAWAKEN in a variety of ways: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrowbookstore, join our newsletter, follow us onFacebook,Instagram, orTwitter or subscribe to ourYouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 102, Glen Arm, MD 21057). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Reasons why I write

By Nikita Rimal Sharma, written July 2022

I don't know how and why the habit started, but I have always had a memory of a notebook and a pen in my vicinity. There have been all kinds of notebook throughout my lifetime. Regular composition, hand-me downs, leather bound, spiral. In the past few years, a Google Chromebook has also accompanied me on days that my thoughts in my head are too fast. However the notebooks look like on the outside, or what form my words take, digital or analogue does not really matter. I just write and fill them with words, my words.

The content has its own variety. Depending on where I am at in life, it seems to take a form of its own. Somedays, it’s a big brain dump of things to do; grocery lists, plants to water, or paperwork I am trying to avoid. It includes my plans and intentions for the days to come, my dreams, hopes, goals, and everything in between. Most days, it’s a reflection on how my life is going. I reflect about events, what has been influencing me or what I am obsessed with. I think and try to make sense of a conversation I had, a life lesson I learned, or I let flow my stream of consciousness. I write about good feelings, when I am filled to the brim with gratefulness, positivity oozing out of my words. I write about my worst fears, moments of defeat and hopelessness when I can’t seem to make sense of the world around me. While processing my thoughts, I also doodle (the few things I know how to draw) while I am writing. These accompanying images may be different versions of a smiley face, floral patterns, hearts, and even stars.

And there is also poetry within the pages. Focusing entirely on a set of words and feelings and turning them into a more structured set of paragraphs never fails to exercise my creative muscles. After the pages are filled, I go through each notebook and tear out the pages that could lead into something more: a poem, a social media post, or just an idea for later. The rest goes into my recycling bin, forgotten once I’ve reached this step.

This is the only way I have known how to live and want to live. All aspects of my life on paper, some wording carefully crafted, some just blurted out. I will continue to do this because this is the only way I know how to be.

There are several reasons why writing has always been present in my life. It is how I take mental snapshots of celebratory moments such as weddings or graduations; let out my heartaches, grief, woes of depression and anxiety; or marvel at the little things that bring me joy. My mind is usually a tangled necklace with knots in several places, crumbled, unaware of its becoming. When I write, each knot starts to loosen and things finally start to make sense. The jumble in my mind straightens and sorts itself to categories. Deeper emotions and rage turn into poetry, random thoughts turn into ideas for living and writing more, to-do lists that seemed to never end now have a clear direction that I can follow without feeling overwhelmed. My memories and stories get a permanent home. When I write is when I get to feel, heal, and sort myself out and make way for more abundance in my life. It gives me a chance to figure myself out, move on from one phase or season to another and ground myself. However, I wouldn’t write if it didn’t give me one thing: joy, pure joy!

Why do you write?

Nikita Rimal Sharma’s sources of joy include lots of writing, contemplating the meaning of life, running as often as her knees let her, hiking, walking, and spending time with her Pitbull Terrier, Stone. Nikita currently resides in Baltimore, Maryland, with her husband and works at B’More Clubhouse, a community-based mental health nonprofit. She is originally from Kathmandu, Nepal. Her debut chapbook, The most beautiful garden was published by Yellow Arrow Publishing in April 2022.

Get your copy of The most beautiful garden today at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/most-beautiful-garden-paperback.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. We recently revamped and restructured its Yellow Arrow Journal subscription plan to include two levels. Do you think you are an Avid Reader or a Literary Lover? Find out more about the discounts and goodies involved at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/yellow-arrow-journal-subscription.

You can support us as we AWAKEN in a variety of ways: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 102, Glen Arm, MD 21057). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Poetry is Not Just for Stuffy Old White Men

By Veronica Salib, written June 2022

Growing up, I spent a lot of time with my nose in a book. I was an awkward sort of kid who didn’t quite fit into my own body and books were a great way to escape that. They were a way to live all the lives I couldn’t quite get my hands on. As I grew into my own body in high school, I let go of that love of reading. I was busier with makeup, school dances, cheer practice, and unrequited love.

In my freshman year of high school, one of my teachers had us all celebrate Poem in Your Pocket Day (April 29). We were meant to each bring in our favorite—or just a poem—and share it with the class. Frankly, I dreaded this. Not only did I have anxiety around public speaking, but what was I going to bring. I didn’t have a favorite poem. I didn’t even have an OK-it-doesn’t-suck-that-bad poem.

I ended up picking a poem that I found posted anonymously online. It was cheesy, rhymed, and all of six lines long but that’s beside the point. That day I heard kinds of poetry that I had never heard before. Lines that perfectly described how I was feeling. People had put words to the emotions I could never quite explain.

Up until that point, I was never a fan of poetry. Poetry to me was written by stuffy old white guys who had no idea what it was like living as a 15-year-old Egyptian girl in a school of mostly white kids.

Now I won’t lie to you; it wasn’t until a year later that I fell in love with poetry. That same teacher introduced me to a spoken word poet named Sarah Kay, who absolutely captivated me. I watched every single one of her videos and every Ted Talk. I bought every poetry book she had written. I spent hours on end going through the recommended videos on her YouTube page.

What I learned was poetry isn’t just for old stuffy white guys.

Who would’ve thought?

Poetry is for women who didn’t quite feel comfortable in their skin. Poetry is for men who are struggling with their sexuality. Poetry is for people of color who had to come to terms with the microaggressions they would face daily. Poetry is for people falling in love and healing from the scars that love tends to leave behind.

Poetry is for mothers struggling to raise their sons to be good men and fathers who are amazed at their daughters’ minds. Poetry is for the angry loved ones left behind when someone passes, and that same loved one 10 years down the line when the wounds have scabbed over. And, believe it or not, poetry is for 15 (now 23) year-old Egyptian girls living in a world dominated by old white men.

Late in college, I began to write consistently for the first time. I was always one to scribble thoughts, but as soon as things got difficult, I shut down, put the notebook away, and hid. When my life got hard, and there was no hiding from the ugly, I decided to lean into it. To journal all the terrible feelings and work through them instead of working around them.

The newfound appreciation for writing returned my love of reading. This time it was slightly different. Instead of reading to escape my life, I ended up reading books about my life. I found authors who wrote about similar experiences to mine and how they grew in the direction of the sun rather than towards the roots from which they came. The comfort I found in the words of a stranger just fueled my own writing more.

When I started to go to therapy and unpack all the issues I had stuffed into a neat little gift-wrapped box, writing became my safe space. The things it was hard to say aloud went down on the paper. It was easy to look at these journal entries, poems, and notes in the margin and identify my feelings. It was like writing them out took me out of the situation and let me acknowledge the hurt I felt and the progress I had made.

Writing is what helped me quit my job. And I know that doesn’t sound like a great thing, but I promise you it is. I worked a job that I thought was an excellent fit for me, it had its downsides like every job did, but if it weren’t for my writing, I would have never realized how exhausting it was to pretend to love something that was sucking the life out of me. It helped me acknowledge my greatest loves to date, reading and writing.

It wasn’t until I skimmed through all my journal entries that I decided to make my major career switch from medicine to publishing. Don’t get me wrong; it was not an overnight decision. I’m nothing if not an anxiety-ridden, pro-con list writing, research-doing neurotic freak. But it was the spark that lit the fire.

And when I did leave my job, made the major career switch, and was met with rejection after rejection, disappointment after disappointment, it was writing that kept me sane. I acknowledged the struggles that I faced, the anger, the fatigue, the outright depression. And still, it was the writing that always made me come back; it was realizing how much I enjoyed my little short stories, how excited I got when a friend asked me to edit their paper, and how I could write pages and pages about lines in a book or poem that resonated with me.

If you asked me today, I wouldn’t say I’m a fantastic writer or poet by any means, but it is a massive part of my life. If you asked me, I would say I write for the girl who was too awkward to go out and live her own adventures. I write for the girl who used to hate poetry. I write for the girl too caught up in the boy who didn’t love her back. I write for the girl who thought poetry was for stuffy old white men. I write for the 15-year-old Egyptian girl in a school of mostly white kids.

I write for the girl who hid from the difficult things. I write for the girl who was brave enough to admit she needed help. I write for the girl unpacking her neat little gift box. I write for the girl who was too clouded by the plan she laid out for herself to realize it was killing her. I write for the girl who quit her job and dealt with all the discomfort of being in limbo. But most of all, I write for the girl I am now. The girl who has finally gotten her foot in the door, has finally begun to let go of the father who hurt her, finally started to listen to her internal dialogue, and the girl who has finally begun to embrace all the things that bring her joy.

Veronica Salib was the summer publications intern at Yellow Arrow Publishing and is currently an editorial associate. She works as an assistant editor for a healthcare media company. Veronica graduated from the University of Maryland in 2021 and hopes to return to school and obtain a master’s in publishing.

*****

Yellow Arrow recently revamped and restructured its Yellow Arrow Journal subscription plan to include two levels. Do you think you are an Avid Reader or a Literary Lover? Find out more about the discounts and goodies involved at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/yellow-arrow-journal-subscription. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

You can support us as we AWAKEN in a variety of ways: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 102, Glen Arm, MD 21057). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Worlds of Wonder: On Art and Community

By Marylou Fusco, written July 2022

For a long time, the image of a solitary writer striving alone was stuck in my head. Being by myself, cut off from all others was how I believed I’d get my best writing done. I tested this theory at a writer’s residency in the Finger Lakes region of New York State. I can’t say that I got a lot of writing done. Instead, I spent most of my time picking through produce at the farm stand down the road from my cabin or hiking trials that overlooked lakes and waterfalls. The words came after I left my cabin and returned to family and friends. And I was only able to share those words after I found a writing community that supported and encouraged me to truly grow.

Every writer is different. For some, finding inspiration or time to write is the hardest thing. For others, the editing and feedback process is the most challenging part. As Yellow Arrow Publishing’s author support coordinator, I’m excited to be a resource to accompany writers through the final steps of the publishing process: publication release and the promotion of their work in a way that feels true to them. Helping promote their work is not only an opportunity to celebrate a single writer, but a way to emphasize Yellow Arrow’s larger commitment to showcasing underrepresented voices.

These past few years, COVID has forced us all to reconsider what community can and should be. We’ve had to get creative in order to find and create support. At Yellow Arrow, we continue to be creative to allow our work to take different shapes and forms. Promotion can be an author sharing their work in a traditional setting like bookstores or cafes or it can be sharing their work in nontraditional public setting like parks and festivals. Public readings are crucial ways to build community and create a way for people to easily access the arts. We had a fantastic time at this year’s Arts & Drafts Festival with chapbook authors Nikita Rimal Sharma (The most beautiful garden) and Darah Schillinger (when the daffodils die) and the 2022 Writers-in-Residence, Arao Ameny, Amy L. Bernstein, Catrice Greer, and Matilda Young. And look forward to Darah’s book launch at Bird in Hand Café on September 30 as well as the Write Women Book Fest on October 8.

Moreover, to honor our community near and far, we have created two new writing and reading opportunities, both which start in September. Write Here Write Now is a virtual monthly write-in session lead by a guest host, exploring a specific theme. And I’m Speaking is an open mic night where readers are invited to share their prose, poetry, or spoken word.

Such events are a visible reminder that the arts are not reserved for a chosen few but available to all. Promotion can also flow into new collaborations or partnerships as we connect with other literary nonprofits that share our vision of a diverse and thriving literary community.

Maybe, most importantly, publication and promotions are about celebrating a publication that took so long to be birthed or the prose/poems that have been growing inside of us for even longer. Every piece of art brought forth on the page or spoken is a radical and affirming act. Especially now.

While it’s true that there are parts of writing we must enter into alone, there are other parts that can be eased through community. Throughout my own journey of writing, publication, and community-building, I’ve come to deeply appreciate what it means to receive and offer support as a writer. This is something I hope to share with other writers.

Unearthing the story or poem is only the start. Every writer has a story to tell and every story is worth telling.

Marylou Fusco grew up in the wilds of New Jersey and knew she was a writer forever. She holds a BA in Journalism from St. Bonaventure University and an MA in Creative Writing from Temple University. She has worked as a newspaper reporter, GED instructor, and ghost tour guide. She is a big believer in the transformative power of art and community. Marylou’s writing has appeared in PopMatters, Carve, the Philadelphia Inquirer, Mutha magazine and various literary journals. She makes her home in Baltimore, Maryland with her husband and daughter.

*****

Yellow Arrow recently revamped and restructured its Yellow Arrow Journal subscription plan to include two levels. Do you think you are an Avid Reader or a Literary Lover? Find out more about the discounts and goodies involved at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/yellow-arrow-journal-subscription. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

You can support us as we AWAKEN in a variety of ways: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 102, Glen Arm, MD 21057). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Ida B. Wells: The Civil Rights Activist Who Used Writing to Fight Racism

By Piper Sartison, written May 2022

To honor Ida B. Wells, whose birthday just passed, Piper Sartison, Yellow Arrow’s winter marketing intern, wrote a short blog about her incredible accomplishments.

“The reason why I wanted to focus on this blog was that I wanted to tell the story and journey behind a monumental and historical journalist. Ida B. Wells used her skills in writing to become an advocate for the voiceless, as she sacrificed everything to fight against oppression. In relation to the current events that surround us today, I hope that this piece will reinforce the significance of journalism, as it has the potential to give a voice to people who are marginalized and need our support.”

Ida B. Wells was a teacher, civil rights activist, journalist, and feminist. Born on July 16, 1862, in Holly Springs, Mississippi, her parents passed away when she was young and so she spent her youth taking care of her siblings. Once she turned 16 (from most general sources), Ida started a career in teaching to provide for her siblings and spent her free time writing for newspapers. In 1882, she moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where she bought a first-class ticket on a train. The crew, however, attempted to force her into a cart that was reserved for African Americans only. Ida refused, and as a result, she bit one of the crew members, who was aggressively removing her from the train. Ida sued the railroad, but her claims were rejected by the Tennessee Supreme Court. This situation influenced her passion for free speech, as she later started her career with the Memphis Free Speech newspaper.

Once Ida gained enough experience in writing, she became the co-owner of the Memphis Free Speech when she was in her 20s. Using this job as a form of advocacy for African Americans, she expressed her opinion on the oppression and racism in society for the public to read. During her time as a journalist, three of her friends got lynched in her community. Ida was outraged and published pieces that outlined the racist truth behind why her friends got lynched. In her piece, she told the people of Memphis to stop shopping at white-owned businesses and encouraged them to move to Oklahoma.

In 1892, Ida moved to New York, as she wanted to write for The New York Age. It was there that she published pieces on the cruelty of lynching, encouraging others to revolt against violence and racism. In 1895, Ida married Ferdinand L. Barnett and had four children with him while they resided in Chicago, Illinois. While also tackling the challenges of motherhood, Ida found time to support the suffrage movement and help found the first kindergarten class for black children.

In 1909, she gave her support to the National Association of Colored Women, based in Washington, D.C., which worked to promote equality and was one of the biggest organizations of black woman clubs in America. In her work with the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago in 1913, she encouraged women in the community to elect politicians that best represented the African American population. Her efforts with this organization ultimately contributed to women’s suffrage in Illinois.

She died of kidney complications in 1931 at the age of 69. Ida was posthumously given a Pulitzer Prize in 2020 for her bravery and advocacy against racism, violence, and sexism. The Ida B. Wells Barnett house, where Ida and her husband once resided in Chicago, is a National Historic Landmark.

Ida sacrificed her life to contribute to the civil rights movement, organizing rallies, creating an antilynching campaign, advocating for African Americans in newspapers, and willingly standing up against the system that deemed anyone inferior. Today, Ida B. Wells is remembered for her courage, strength, and immense intelligence. In her life, she stood up to injustices, and spoke up about systemic racism, invoking significant change within her community.

Piper Sartison is a rising junior at Washington College. She is a competing member of the school’s tennis team, writes for The Elm, and is a major in English and a minor in journalism. Piper is from Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and will be residing there for the summer, where she hopes to do some freelance writing.

*****

Yellow Arrow recently revamped and restructured its Yellow Arrow Journal subscription plan to include two levels. Do you think you are an Avid Reader or a Literary Lover? Find out more about the discounts and goodies involved at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/yellow-arrow-journal-subscription. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

You can support us as we AWAKEN in a variety of ways: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 102, Glen Arm, MD 21057). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Craft Thoughts: Honoring the Poem’s First Draft

By Joanne Durham, written April 2022

I enjoy participating in groups with other women who come together to write and then share our first drafts. But too often we expect those drafts, from 30 or 40 minutes of writing (sometimes even less), to sound like finished poems. If not, we feel like we’ve failed and aren’t good writers. We can spend more time apologizing for what we’ve drafted than noticing what is working!

When I first started writing poetry, I thought that the first draft was supposed to be the final. I thought because I wrote poetry to get emotional truth on paper, I would spoil it if I revised it. I might fix grammar or a word here or there, but if the poem didn’t resonate, I just put it aside and forgot about it.

All that changed when I taught children in a writing workshop. I learned that by conferring with them about their intentions and teaching them some simple elements of craft, they could transform their first drafts into rich and meaningful poems for themselves and other readers.

In a marvelous section of her Living Room Craft Series on Revision, Ellen Bass shared the first draft of James Wright’s poem, “Hook,” from an interview released by his wife. I had loved this poem for a long time. I was so amazed that almost the entire final poem didn’t show up until the sixth verse in his first draft! It was by stripping away everything from the original that didn’t support the dramatic center of the poem that he gave the poem its intense substance and power.

So, I’ve come to think of my first draft as just scattering seeds. It’s the nurturing I give my poems over time that shapes them into something that might blossom. The crocuses in my yard will lift up through the dirt with no help at all from me. But lots of poems, like flowers, need the support we call revision. Often, it’s pruning, so what is lovely has room to flourish, and fertilizing to add richness to the language.

Pruning, as in Wright’s wonderful example, helps me let go of expectations and just let my writing flow. I know I can go back later and get rid of all the unnecessary verbiage. For example, in my poem, “BABY!” (RENASCENCE, Yellow Arrow Journal), I wrote about my joy and wonder at the sonogram of my first grandchild. My first draft of “BABY!” started:

Rachel texts the picture today

of what will become our grandchild.

Looks like a little island

in the midst of ocean whitecaps

and BABY! with a finger pointed

to the blob, so you know

where to look.

And a thumb

holding the picture

putting its size in perspective,

this is what 11.5 cm (what it says at the top)

is – the size of a few thumbs. Her name and birthdate

I recognize. The other numbers and letters

in language you just have to trust

to the midwives.

I wrote all that to get the details down on paper. But as the poem developed, I realized what I really wanted to explore was the connection between this unborn child and my Jewish ancestors, that this child would exist only because they had escaped the pogroms of Russia. The phrase “God willing” came up—a phrase my parents and grandparents would have used. Then I knew I didn’t need all those details before I got to the heart of the poem. So (over several drafts) I revised:

Rachel sends the sonogram today

of what will become (God willing)

our grandchild.

Looks like a bean

in a soup bowl. Someone

thoughtfully wrote BABY!

with an arrow pointing to it,

to tell us where to look.

God willing isn’t something

I’m known to say, but this child . . .

Pruning isn’t usually enough; fertilizing needs to happen as well. I often need to find a richer, more musical, more powerful, or more multi-faceted way of saying something I jotted down in the first draft.

“Sunrise Sonnet for My Son,” is the last poem in my poetry book, To Drink from a Wider Bowl (Evening Street Press April 2022). The poem was inspired by how my son and I both found our morning chore of unloading the dishwasher to be something meditative. My first draft ended,

I think of him each morning, this son I raised, who takes joy in putting away the dishes.

I got the idea on paper, but not the poetry of it (no blame, first draft!). It needed some fertilizer. I let it sit a while, let my imagination come up with specifics that would both sound musical and enhance the imagery of the poem, and days later wound up with

this man I raised, who hums as he sorts

the silverware, noticing how each spoon shines.

There are certainly some poets who can distill the poem on the first draft and dazzle us as they share in writing sessions. But I’m so glad I didn’t toss either of these poems because they didn’t fulfill my expectations on the first try. Realizing that I can nurture the poem over time—days, weeks, months, whatever—helps me enormously to believe that my first drafts can lead to something I’m happy with. In that sense, “BABY!” could refer to the embryo of the poem as well as the one in my daughter-in-law’s womb when I wrote:

. . . I’ll send something

resembling a prayer

that it thrives in that watery mix,

that it emerges, in its time,

whole and ready . . .

Joanne Durham is the author of To Drink from a Wider Bowl, winner of the 2021 Sinclair Poetry Prize (Evening Street Press 2022). Her chapbook, On Shifting Shoals, is forthcoming from Kelsay Press. Her poetry has or will appear in Yellow Arrow, Poetry South, Poetry East, Calyx, Rise-Up Review, Quartet, and many other journals and anthologies. She is a retired educator from Maryland, now living on the North Carolina coast with the ocean as her backyard and muse. Get your copy of To Drink from a Wider Bowl at eveningstreetpress.com/book-author/joanne-durham/. Learn more about Joanne at joannedurham.com or on Instagram @poetryjoanne.

****

Yellow Arrow recently revamped and restructured its Yellow Arrow Journal subscription plan to include two levels. Do you think you are an Avid Reader or a Literary Lover? Find out more about the discounts and goodies involved at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/yellow-arrow-journal-subscription. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

You can support us as we AWAKEN in a variety of ways: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 102, Glen Arm, MD 21057). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Why I Write Creative Nonfiction

By Melissa Nunez, written December 2021

I will never forget the mix of anger and incredulity coursing through my body during my first fiction workshop. As the author, I sat silent as my peers debated not the style or form of my piece submitted to the class, but the credulity of my words. “There’s no way all this happened to one person,” spoken in various versions and on repeat. And I was peeved. It did all happen. It happened to me. The death of my best friend, the disastrous dissolution of my parents’ marriage (and the resulting familial fallout), the abortion, the love triangle, the abusive partner. As if the dramatic and tragic politely take turns in the timeline of your life, giving each event exclusive spotlight shine. I wanted people to believe all these things happened to someone, successively and simultaneously, but was unwilling to claim that someone as me. It took me a semester of battling this wariness, of defending the veracity of characters and probability of plots before finding my home in the Creative Nonfiction chapter of the MFA program.

This decision involved more than logical next steps, more than simple solution. It was not just hanging three letters, the n o n, in front of the word fiction. It was letting go of all the stigma that came to mind with putting my unfiltered self out into the world. And there was still the craft of it, the charge of engaging your audience, of giving them reason to read and heed your words. There was still deciding what to say, how and when to say it. Which experiences to detail, to what length or breadth, and how to organize them on the page. When you get right down to it, there are so many possibilities even with a single happening.

There should be a sense of truth in all writing but deciding to only write what is true was both liberating and distressing. I love the fact that everything around me is my possible next story. The words I speak and those spoken to me tumble around in my head and many end up in the notes app on my phone or the pages of my notebooks. Conversations with my children or husband, insightful lines from a book or television show that make a certain idea click into place. That part comes easy to me as a naturally introspective person. The hard part comes after. In having my thoughts and perspectives, experiences and emotions laid bare to be scrutinized by others. It is something I live so many times in my own mind as I write, on amplification when I’m actually getting feedback. I channel the strength of those before me who have told their stories bravely, stories that have impacted my life and the lives of others. Books like The Other Side by Lacy M. Johnson (where she frames visceral vulnerability within a deeply insightful and moving metaphor), Paula by Isabel Allende (masterful amalgam of maternal missive, memoir, and elegy), and the collected essays of Samantha Irby (whose words are an homage to honesty and self-acceptance in the most raw, real, and hilarious forms).

Every time I write, I learn something about myself and the world around me. Things I was previously unaware I needed or wanted to know. Because of creative nonfiction, I have gotten to better know family members, both close and further distant. I was introduced to my great grandfather for the first time and was shown pieces of my grandfather previously unshared in conversation with my great aunt. I have become better able to identify the plants that grow along the canal banks and nature trails close to my home, the birds and insects that dwell there. I plan to plant Turk’s Cap, a hummingbird favorite, in my yard this coming spring and make further strides towards de-lawning. I hope to include some nopales, set along the back fence to avoid accidents, as I have recently discovered that the prickly pear is one of my favorite fruits, seeds and all. Because of creative nonfiction, I am now too aware of the microscopic arachnids that make their homes in our skin, of the bacteria exchanged with those around us independent of physical contact. I have discovered the shared root of my most painful choices, listed among the “unbelievable” events above.

I have come to love the act of self-discovery as art, as communion with the world around me, as conversation with others who also watch for wonder. With those who are willing to rethink everyday experience, to revisit rumination often dismissed as mundane, to combine and recombine these moments in novel ways—here Creative Nonfiction transforms, is made something more magical.

Melissa Nunez is a homeschooling mother of three from the Rio Grande Valley region of South Texas. She is a staff writer for Alebrijes Review. Her essays and poetry have also appeared in FEED, Lammergeier, and others. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook @MelissaKNunez.

*****

Yellow Arrow recently revamped and restructured its Yellow Arrow Journal subscription plan to include two levels. Do you think you are an Avid Reader or a Literary Lover? Find out more about the discounts and goodies involved at yellowarrowpublishing.com/store/yellow-arrow-journal-subscription. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

You can support us as we AWAKEN in a variety of ways: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 102, Glen Arm, MD 21057). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Confessions of an Unschooled Poet: Learning that Some Rules are Meant to be Broken

By Amy L. Bernstein

I first composed a poem as an adult around 1986. I read it out loud to my boyfriend at the time, my whole body shaking. Sharing an original poem handwritten on a scrap of notepaper, after several hasty drafts, seemed like a subversive act. I had never felt more vulnerable or exposed than when reading those lines.

That poem did not survive and neither did the relationship. All I can recall (about the poem, not the guy) is that I used metaphors involving textiles to express something about the act of creative writing itself. I think the last line went something like, “In the end, the poem sews itself.”

After that little experiment, I did not write another poem until early in 2019—three decades on. I didn’t know how. I didn’t think I should. I didn’t feel qualified. I assumed I couldn’t simply barge into the world of poets and poetry and find a berth.

After all, as an English literature major in college, I had read tons of so-called classic fiction, from Shakespeare and Chaucer to Thackeray and Eliot. But I did not take a single poetry class (if you exclude Shakespeare) and I did not read poetry for pleasure.

Poetry struck me as an entirely separate branch of literature, off in its own corner, speaking to the cognoscenti. Either the cryptic lines yielded up their secret messages to you—invited you to decode their meaning—or they didn’t. Poetry had rules! So many rules! I knew how to write topic sentences and coherent paragraphs; I knew how to develop and support a thesis statement.

But poems snaked along the page like hieroglyphics, and I lacked the knowledge to decipher or unpack them. I didn’t know a sestina from a villanelle. I figured if I wasn’t willing to study the rules, then I couldn’t (and perhaps, shouldn’t) attempt any of the forms.

Which is not to say that I was totally immune to all of poetry’s seductive charms.

There were moments over the years when a poem (mainly from the traditional Eurocentric canon I was exposed to) briefly turned my head. “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg (I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness . . .). T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (In the room the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo.). Snippets of Walt Whitman (I sing the body electric—a great line in an otherwise not-so-great piece). Amiri Baraka’s chilling, incantatory “Somebody Blew Up America” (who WHO WHO . . .).

But I continued, for the most part, to hold poetry at arm’s length. I left the form to those who were perhaps more patient, more intuitive, or maybe just smarter, than I.

Then came 2019 and something shifted. Was the shift in me, as a writer finding my voice in different forms (playwrighting, novels, essays)? Was the shift occurring in the wider world, given rising levels of injustice, civil unrest, uncivil discourse? I believe it was both.

I sat down at my computer one day four years ago and recognized that a poem was the only form adequate to expressing what I needed to say, just then. I was in the grip of a mild depression, feeling raw—and feeling too much.

Paradoxically, poetry’s stringent economy of language is well suited to big emotions. Compression of form yields expansion of expression.

My subconscious must have understood that premise when I began writing poetry. I dove in because I wanted to, needed to. I cast aside self-conscious concerns about not knowing what I was doing. I wouldn’t let my lack of formal mastery get in the way of what I wanted to say.

First lines from a first poem:

Nothing is wrong with you / You are a glassine harbor on a windless day.

I wrote only free verse from then on (and still do), on the theory that I’m not equipped to compose in more formal forms. I still don’t know a sestina from a villanelle, but so what?

Now, I love making more with less; scraping words away until only the necessary ones remain; finding precisely the right metaphor to create both image and feeling. I love the look of a completed poem on the page, how the ragged lines and unpredictable line groupings keep your eyes moving and the rhythms flowing.

I love how a poem can’t be anything other than itself. Form follows function.

I’m still an uneducated poet. I don’t routinely read poetry, though I do listen to it on a semi-regular basis. I don’t expect I’ll ever grasp more about poetry as an art form than my own practice teaches me.

While others may fault me for my attitude, I’m okay with it. Writers should follow their muses, wherever they lead—or don’t lead.

The lesson I’ve learned from my late lurch into poetry, which I’d like to share with writers everywhere, is that you should always allow your creative heart to be your guide. There is no art form that is off-limits; no door that is closed to you; no club to which you may not belong as a writer, when it comes to the marriage of form and subject matter.

Even though I still hesitate to call myself a “poet,” I fully embrace the act of writing poetry. After all, the label is not what matters. In the end, it’s all about the work you create and share, in any form you dream up. Honor your calling, no matter what it’s called.

Amy L. Bernstein writes for the page, the stage, and forms in between. Her novels include The Potrero Complex, The Nighthawkers, Dreams of Song Times, and Fran, The Second Time Around. Amy’s poetry leans heavily on free-form prose poems that address psychological and political states of mind. Amy is an award-winning journalist, playwright, and certified nonfiction book coach.

Visit her website and follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. Thank you for supporting independent publishing.

You can support us as we AWAKEN in a variety of ways: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 102, Glen Arm, MD 21057). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

The Publishing Dilemma

By Angela Firman, written March 2022

One of my favorite ways to start a writing session is to open unfinished documents I’ve saved to find a seed worth nourishing. I feel like a genius when a tangled effusion of words from the past awakens my muse, and I set to work. When a piece comes together, what’s next? Dare I share it with others? I created something I am proud of, but when my words go out into the world, they invite others in; specifically, other’s judgement. I don’t generally live in fear of what other people think of me, but when it comes to writing, I am as bashful as they come.

There are writers who do not grapple with the decision to publish or not. Maybe it is because they have thicker skin than I do; they can take an arrow right to the heart without shedding a drop of blood. I am of the kind that dramatically clutches their chest and staggers to the ground, spurting blood every which way. Yes, judgment can be both bad and good, but even if there is only one bad comment among hundreds of good ones, I tend to dwell on the unkind one. Fortunately for my thin skin, I do not have hundreds of comments trailing after my writing, but if I did, it’s not the strangers’ opinions that terrify me: it’s my loved ones’. I have the most to lose with them because something worth publishing is juicy. It is the vulnerable material we hide, the words that will resonate with someone who recognizes themself, and sighs with relief to learn they are not alone.

I recently shared a piece in a writers’ workshop about grappling with being an accomplice to racial injustice while growing up in a predominantly white suburb of the Midwest. The in-person feedback I received left an indelible impression as I watched tears flow from other white women’s faces and heard affirming words from women of color, urging me to publish the piece to contribute to the ongoing, painful conversation in our country. This is important to me but sharing it would be at the cost of my parents’ feelings. I don’t imagine they would enjoy reading a public account of the shortcomings of the community I grew up in. At no point do I call them out, but how could they not feel responsible in-part for the pain I feel? This is just one example of vulnerability. My mom-friends could read about my preference to work rather than stay at home with my kids, or my in-laws could read about my struggles with anxiety and depression. Is a connection to a stranger I may not ever hear about worth the potential negative judgment I could receive from the ones I love?

I don’t know.

But I do it anyway. It makes me feel good to see my words in print. It not only validates my writing, but also my feelings. The magic of the written word—and any art, really—is its ability to express the infinite ways the human condition is experienced. No two artists have the same background or beliefs, so their work is a testament to their unique worldview. What better way to learn and affirm than to see the world through another’s eyes?

When the ones I love, often unintentionally, share their opinions and pierce my paper-thin skin—I won’t lie—it hurts. But I let the blood gush, I wallow in it a bit, and as time does, it heals all things—including my wimpy, thin skin. Wondrously, after I heal, my skin is a bit tougher than it was before. Scar tissue can do that. The barb of criticism will have to dig a little deeper each time in order to wound me. And so, I submit, sending my experience into the wide world in search of those who need to hear it.

Angela Firman is a Midwesterner at heart living a Pacific Northwest life with her best friend and their hilarious, sometimes demanding, roommates aged 4 and 8. Angela is an avid reader, a closet-cross-stitcher, and a fervent writer. While she has always enjoyed journaling, writing became a source of healing for Angela after being diagnosed with Stage III breast cancer at the age of 33. She found a place in the literary world in a writing group for breast cancer survivors—women who have grown to be some of her dearest friends—and now at The University of Washington where she is earning a certificate in editing. Her nonfiction writing has been published in Wildfire Magazine, Open Minds Quarterly, You Might Need To Hear This, and Press Pause. You can find her on Instagram @angelafirman11.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

You can support us as we AWAKEN in a variety of ways: purchase one of our publications from the Yellow Arrow bookstore, join our newsletter, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter or subscribe to our YouTube channel. Donations are appreciated via PayPal (staff@yellowarrowpublishing.com), Venmo (@yellowarrowpublishing), or US mail (PO Box 102, Glen Arm, MD 21057). More than anything, messages of support through any one of our channels are greatly appreciated.

Everything is Practice

By Matilda Young

The great Brazilian soccer player Pele said, “Everything is practice.”

As both a writer and soccer nerd, this quote is dear to me. Over the years, it has come to mean different things: how honing a skill requires us to put the hours in, how every moment is an opportunity to learn.

These days, it helps to take some of the pressure off. When I’m out here taking a stab at a poem or an essay or a story, I’m just kicking the ball around, seeing what feels right, finessing my footwork.

Over the past four years, I’ve done my own version of NaNoWriMo, attempting to write a poem a day during April. I started out by participating in Tupelo Press’ 30/30 Project in April 2019. In the years since, I’ve been doing it on my own.

Well, not really on my own. In fact, the best part of the practice has been doing it alongside other writers. Every year, I invite writers I know to join me in a series of messy Google Docs, one per week(ish). It’s an open invitation for folks to forward along to others—my view is the more the merrier!—which has meant I get to write alongside some tremendous writers I’ve never had the pleasure to meet except on the page.

Every day, I’ll put a prompt in the Google Doc that people can respond to (or not). People can put their drafts in the Doc (or not). People can write every day or write whenever it makes sense for them.

It is such a joy to read what folks are writing throughout the month and to see what they create (we have some folks who are also visual artists). Everyone’s style is so different, and no one tackles the prompt in the same way. I am blown away by everyone’s talent, by these wonderful glimpses I get into their writing lives.

And especially during the pandemic, getting to be in community with these writers has been a lifeline. That first April, in 2020, when we were all so cut off from the world and from each other, writing together gave me a glimmer of hope.

This poem a day practice also paradoxically takes the pressure off for me. I can’t let perfect be the enemy of good. The poem doesn’t have to be something that’s publishable or finished or more than a few scraps of lines; it just has to exist.

I haven’t figured out a way to carry this daily practice beyond April. I don’t know if I ever will. And that’s OK—I’m still practicing.

Everything is practice. For me, this is practice in the spiritual sense, too. Writing together every April reminds me why I love writing, why I love writers. And I think everyone who loves writing is a writer. Everyone who loves language is a writer. Everyone with a truth they need to put into words is a writer. And in some small way, in these Google Docs, I get to be part of a jam band of folks who are sharing their truth with the world.

I hope that maybe you and your friends, and fellow writers not yet friends, will give this a shot and make it your own. It doesn’t have to be April. The prompts don’t have to be longer than one word (cardinal, crunch, clasp). But it may be a practice that you will find meaningful.

If not, that’s OK, too! We’re just out here figuring out what feels right for us, finessing our footwork, kicking the ball around.

“In Gratitude For Google Docs – April 2021”

This morning, I tried a new trick – wet rubber