Yellow Arrow Publishing Blog

Can Old Testament Stories About Women Sing to Us Today? A Review of Manna in the Morning by Jacqueline Jules

By Naomi Thiers

I think it’s fair to say the Old Testament itself is a character in Jacqueline Jules’ recent poetry collection Manna in the Morning. Bible stories and personages, including those lesser known, are the central element in so many poems that the Old Testament becomes a presence as we read—not oppressively, but in a way that probes freshly what’s going on with those old tales and weird, flawed characters.

This includes female characters beyond the usual Eve and Esther: Dinah*, Miriam*, Jochebed* and more (just for fun, throughout this review I’ve marked lesser-known female Biblical characters Jules write about with a * and there’s a key at the end!). Even poems that don’t focus on Old Testament stories or characters swirl around the author’s spirituality as a Jewish woman. They bring into Jules’ thinking about her life in the 21st-century metaphors or life lessons from people and situations in Genesis, Exodus, the prophets, etc.

Jules’s poems are built with straightforward statements and elemental images that lift from the ordinary through pithy lines and repetition. Her best poems use a touch light enough for the energy she’s drawing from old stories to come wrapped in mystery. Consider the entangling of modern marriage with Adam and Eve in “Prenuptials”:

Vows exchanged. Papers signed.

Will they bind me back to Adam’s rib?

To move from that day on

in synchrony, for fear

of ripping apart the flesh we share.

Eve was a bulge beneath the armpit

whittled when the first wife, Lilith,*

ran away. Must I leave the garden,

become a demon,

to preserve the person

who precedes the wedding?

Wonderful are those poems in which Jules lets in the darkness (which does flood many Old Testament stories) and probes deeper into tales of Biblical women who go almost unnamed even when they’re essential to a story. As “Wondering about Dinah and Leah” says, “Bible stories are skeletal, bones/fleshed out through exegesis--/ words, sentences, translations/ scrutinized, interpreted./ And most dwell on the men, on actions, not emotions.” Jules speculates on aspects of lives that are tiny footnotes in the Old Testament, such as (in the same poem), Dinah, whose rape sets off family vengeance:

. . . we don’t hear from Dinah

herself, only what was done to her.

And we hear nothing from Leah,

her mother, who should have been waiting,

worrying, ready to comfort.

Did Dinah find solace with Leah?

The woman remembered

as the unloved wife, the one forced on

Jacob instead of the sister he favored.

I wonder as I read the exploits of men.

Perhaps because I’ve chosen a faith (Quakerism) which holds to continuing revelation—that anything we know about God or our connection with God is forever evolving, being newly revealed. I love what Jules does in “Hannah’s Heart.” She shows the significance—in the journey of Jewish spirituality and Jewish people’s sense of how they relate to God—of a personal act, Hannah* crying out to God because she’s barren. A woman who can’t have children weeping—nothing to see there, right? But “Hannah’s Heart” implies that this ordinary woman’s tears were a turning point:

Before Hannah wept

in the sanctuary at Shiloh,

we didn’t believe it possible

to beseech the One above

without blood.

We burned bulls to please.

Men measured portions.

More for the fertile wife.

less for the barren one.

Unfortunately, some poems don’t let the implications a Biblical story may have for folks today float through the language and images—they stick up a signpost. Phrases point firmly to the “lesson.” “Esau’s Choice” considers why Esau forgave Jacob, who conspired to steal his inheritance, saying simply: “The Bible reveals no details, no reason/ why Esau kissed his brother and wept. // We can only imagine. . .” Before the reader has time to let that language lead them to ponder their own family betrayals, the poem preaches: “Hope that Esau’s choice/ will be the one we choose.” “Facing the Wilderness” follows a subtle description of two Israelites who were rewarded for having great faith with “An instructive tale for me,” and a poem musing about how much toil went into building a tabernacle, as told in Exodus 25, closes with “Inspiration for me/as I struggle to build/ a space inside my heart/ where holiness can dwell.”

As a person who takes a spiritual life seriously, I appreciate what Jules is doing. Bible stories, chewed on, can give us strength to build a space inside “where holiness can dwell.” Jules dedicates the book to “my Mussar group at Temple Rodef Shalom, Virginia” (Mussar is an ancient Jewish spiritual practice that explores how to live an ethical inner life, not just follow rules). She’s writing out of a deep-rooted tradition dedicated to exploring how contemplation of scripture brings us closer to our heart, to holiness. And many poems—like “Queen Esther”—do invite us to explore, without stressing a “lesson”:

“If I if I perish, I perish

The young woman tells the mirror.

Donning jewels and perfume,

she strides in silk gown toward her fate.

“If I perish, I perish.”

Is it really courage that lifts her chin?

A noble choice to swing from the gallows

rather than hide in silence?

“If I perish, I perish.”

Or does action offer its own rewards

when you’re likely to hang

by the neck either way?

I’ll end with my favorite poem, “Dialogue with the Devine”—a woman finding her way toward joy in the work of keeping the faith:

When I petition,

I’m on my knees, bruised,

by the hardness of the floor.

. . . obsessed by the squish

of mud under my sandals,

ignoring the Red Sea,

miraculously parted.

When I praise,

I’m on my feet, billowing

like clouds in the sapphire sky.

I’m Miriam*

holding a tambourine,

dancing in the desert, grateful

for the smallest excuse

to sing.

KEY: Dinah, daughter of Leah and Jacob was (the text implies) raped by a Hivite; her brothers took revenge on all the Hivites. Miriam, Moses’ sister and a prophetess, sang when Pharoah’s army was destroyed. Jochebed, Moses’ mother, placed him in a basket in the river to save him from Pharoah’s command to kill Jewish male babies. Lilith was Adam’s wife before Eve. Hannah gave birth late in life to Samuel, who became a Hebrew judge.

Jules, Jacqueline. 2021. Manna in the Morning. Kelsay Books. kelsaybooks.com.

Naomi Thiers (naomihope@comcast.net) grew up in California and Pittsburgh, but her chosen home is Washington D.C./northern Virginia. She is the author of four poetry collections: Only the Raw Hands Are Heaven, In Yolo County, She Was a Cathedral, and Made of Air. Her poems, book reviews, and essays have been published in Virginia Quarterly Review, Poet Lore, Colorado Review, Grist, Sojourners, and other magazines. Former editor of the journal Phoebe, she works as an editor for Educational Leadership magazine and lives on the banks of Four Mile Run in Arlington, Virginia.

******

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. Thank you for supporting independent publishing. If interested in writing reviews about recent books written by authors that identify as women (largely from other small presses), email editor@yellowarrowpublishing.com.

Foundations in Seeking: The significance of ‘Yellow Arrow’

By Gwen Van Velsor

In the summer of 2014, I started to walk The Way. Life had completely crumbled back home in Hawai’i, and I’d hit bottom. So here I was, rising with the sun each morning to guzzle instant coffee and walk, one day at a time, one step at a time, 500 miles across northern Spain on the Camino de Santiago.

For the first time in my life, one day at a time meant something tangible. I would walk from one village to the next, find a place to get food, wash the only set of clothes I had, take shelter in a crowded dorm, and most importantly, follow the bright yellow arrows emblazoned along the path.

Life became very simple. A little bread, cheese, and sunshine brought much happiness. Making tea by the side of the trail with foraged herbs and a little camp stove became ritual. The crunching sound of feet on stone a rhythmic prayer. Every day I left something behind to lighten the load: a shirt, a pair of sandals, a festering resentment, mistrust of my own body.

I walked the Camino del Norte (there are various routes pilgrims can take) along the northern coast through Basque country, Rioja, Asturias, and Galicia. In the city of Oviedo, I joined the Camino Primitivo through the mountains known for being rugged. I wanted it to be physically demanding, even punishing maybe, some version of penitence. For weeks I just walked all day into the sun, flopping down on a bunk each night. Along the way there were friendships, encounters with God, angels, love, cats, and lots and lots of yellow arrows. The arrows appeared on regulation cement markers, tree trunks, telephone poles, boulders, sidewalks, houses. After the first few days of anxiously looking for each one, I began to trust they would be there, I began to realize that all I had to do on this journey, the only task at hand, was to follow the arrows.

Everything else in life, my failures and anxieties, my plan for the future, my past hurts and pain, fell away as I walked, and walked some more. I gave all of these over to a higher power and trusted that one step at a time, I would get where I was going.

The ancient Way is worn smooth by the feet of millions of pilgrims. I thought, many times, of the seekers who came before me and those that would come after. I took my place as one of many.

I returned to the U.S. from this trip without a plan. Without the trail and yellow arrows in front of me, I had to lean on intuition, stepping toward the next right thing, one day at a time. I was eventually led to the mountains of Colorado later that year. I took a chance on a serendipitous opportunity and opened a coffee shop in the basement of a library. I named it Yellow Arrow Coffee. Oh my, what adventures were had and what amount of caffeine was made and consumed. I found deep grace and purpose in that basement, and met people, so briefly, who changed me forever. That journey, however, also came to an end and I found myself in Baltimore, Maryland by the end of 2015.

In 2016 I had just given birth to my baby girl and my first book (called Follow That Arrow, no less). Something was lingering in my heart and creative ambitions. I wanted to give back, to give voice to more creatives. Sam Anthony and Leila Warshaw helped turn this seed of an idea to start publishing others’ work into a full-blown, life-consuming passion. Kapua Iao came along, put wheels on it, and made the thing move. Ariele Sieling believed in me and this idea long before I ever believed it would grow the way it has. And you, all of you, saw something in our work and said, yes. I am tempted here to include a long section on gratitude for the multitude of women who have collaborated on what is now Yellow Arrow Publishing. But that is a story that stands on its own. For now, my love letter to all of you, as you stand on the smooth stones of women writers and artists, taking your place among all those who have come before and will come after, is to follow the arrows wherever you are and wherever you go.

As my own arrows take me away from this work, please know that it is one of the great joys of my life to see how Yellow Arrow Publishing is unfolding in your beautiful hands.

Gwen Van Velsor writes creative nonfiction and pseudo-inspirational prose. She started Yellow Arrow, a project that publishes and supports writers who identify as women, in 2016. Raised in Portland, Oregon, Gwen has moved many times, from sea to shining sea, now calling Bosnia her home. Her major accomplishments include walking the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage in Spain, raising a toddler, and being OK with life exactly as it is. She is the author of the memoirs Follow That Arrow (2016) and Freedom Warrior (2020), both published by Yellow Arrow (but sold out in our bookstore!) and available on Amazon.

*****

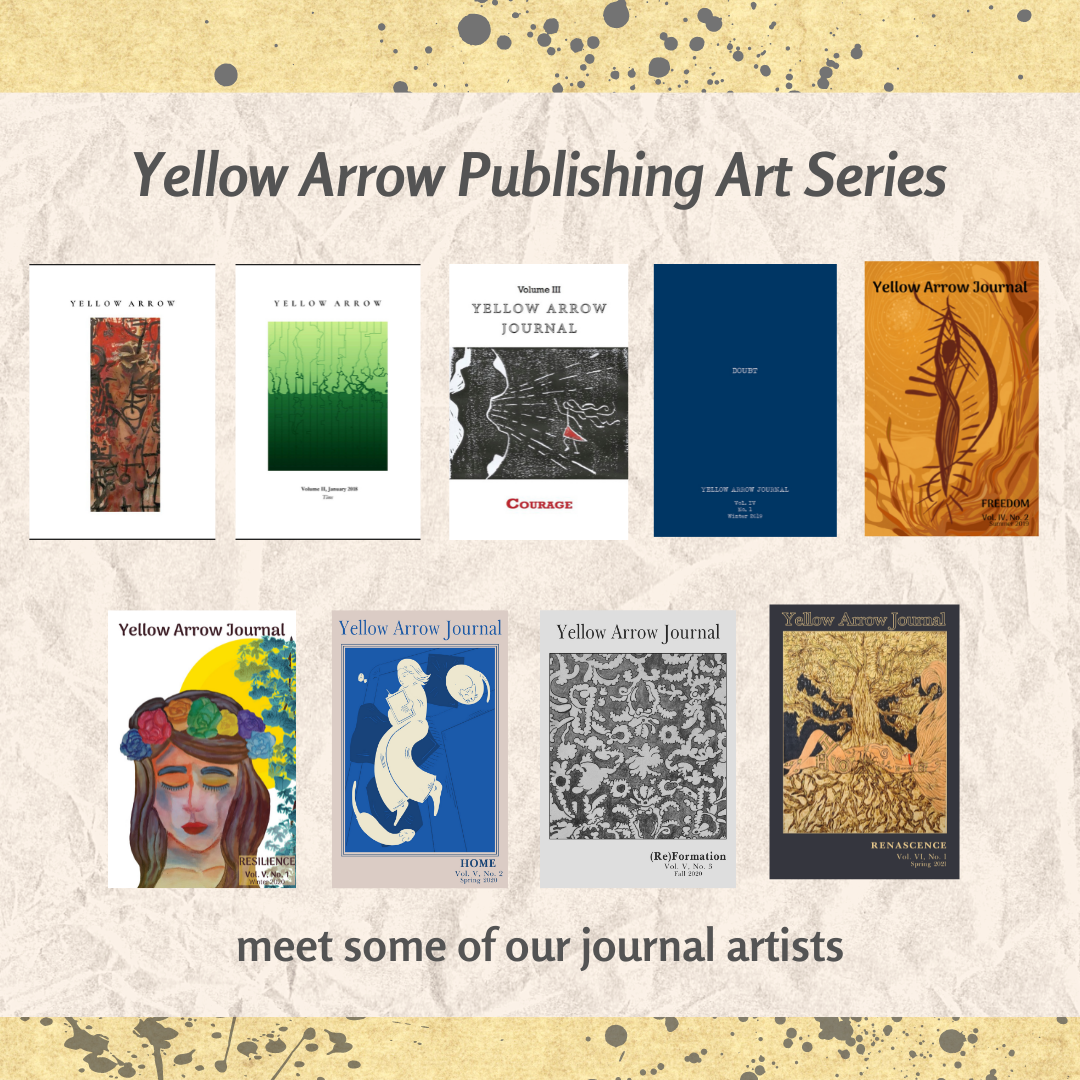

Thank you, Gwen, for all that you started and for showing us the way. We at Yellow Arrow are still just following the arrows, supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. Every writer has a story to tell and every story is worth telling. Show your support of such a great mission by purchasing one of our incredible publications or donating to Yellow Arrow today. Thank you for supporting independent publishing.

Listen by Ute Carson: Exchanging Stories

Yellow Arrow Publishing announces the release of our latest chapbook, Listen, by Ute Carson. Since its establishment in 2016, Yellow Arrow has devoted its efforts to advocate for all women writers through inclusion in the biannual Yellow Arrow Journal as well as single-author publications, and by providing strong author support, writing workshops, and volunteering opportunities. We at Yellow Arrow are excited to continue our mission by supporting Ute in all her writing and publishing endeavors.

Listen spans the life cycle: birth, parenting (and grandparenting), aging, and dying. Images of nature and our connections to it abound throughout because nature is our habitat. The cover further invokes this symbiotic relationship. The poems within Listen run a full gamut of human emotions—wonder, doubt, pleasure, regret, love, loss, enchantment, and more, all woven into the fabric of lived experience and of experience imagined.

Ute Carson, a German-born writer from youth and an MA graduate in comparative literature from the University of Rochester, published her first prose piece in 1977. Ute has since published two novels, a novella, a volume of stories, four collections of poetry, and numerous essays here and abroad. Her poetry was twice nominated for the Pushcart Award.

Paperback and PDF versions of Listen are now available from the Yellow Arrow Bookstore. If interested in purchasing more than one paperback copy for friends and family, check out our discounted wholesale prices here. You can also search for Listen wherever you purchase your books including Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Kobo. To learn more about Ute and Listen, check out our recent interview with her.

You can find Ute at utecarson.com or on Facebook, and connect with Yellow Arrow on Facebook and Instagram, to share some love for this chapbook.

***

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. To learn about publishing, volunteering, or donating, visit yellowarrowpublishing.com. If interested in writing a review of Listen or any of our other publications, please email editor@yellowarrowpublishing.com for more information.

Lunchbox Moments: A Zine to Emphasize the Importance of Community

By Rachel Vinyard

We aim to provide a platform for AAPI voices to express:

1. anger and shame roused by racist microaggressions we may have experienced in relation to our cultural foods,

2. pride, joy, and other emotions relating to our cultural foods, and

3. how we have integrated deeper practices emerging from these experiences to honor those emotions.

When I was first introduced to the Lunchbox Moments zine and its mission, I was ecstatic to learn more. I was excited to know that there was a zine that gave the AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islanders) community a platform to speak their truths and talk about very real issues that haven’t been widely discussed until recently. When I sat down to read Lunchbox Moments, it felt as though I were experiencing a world that was unique from mine. A world of fear, shame, and hurt brought on by ignorant, unapologetic people. Diversity is important for storytelling because every story is worth being heard.

Food is an especially important thing to immigrants because it keeps them connected to their culture. Lunchbox Moments is a zine that eloquently and beautifully portrays real stories about the struggles and xenophobia in the AAPI community regarding their food culture. Created by Anthony Shu, Diann Leo-Omine, and Shirley Huey, this zine showcases 26 AAPI writers, including Christine Hsu whose creative nonfiction piece “Mother Tongues of Confusion, Shame, and Love” appeared in Yellow Arrow Journal, Vol. IV, No. 1, Renascence. The zine is a compilation of a variety of different experiences regarding food in the AAPI community. Lunchbox Moments also supports Chinatown’s Community Development Center (CCDC) in San Francisco.

Anthony, Diann, and Shirley recently took the time to answer some questions for us.

Please introduce yourselves and tell us how you decided to work together to create Lunchbox Moments. Why Lunchbox Moments?

Anthony: We met at the San Francisco Cooking School’s Food Media Lab in 2019 and had always wanted to work on a project together. Lunchbox Moments was born out of the pandemic and discussions of race and inequality that dominated 2020. As we went through various ideas on how we could collaborate, we witnessed increased attention on Anti-Asian hate crimes in early 2021. For me, this time period reinstated the importance of uplifting Asian American voices because our stories often go untold. How can we address discrimination against AAPI communities when our country lacks a shared discourse or knowledge of who this group encompasses/our history/our struggles? The theme of lunchbox moments was a way for us to combine our interests in food/food media with sharing Asian American experiences.

Diann: Lunchbox Moments came about because of the perfect storm, really. Food media is still overwhelmingly nondiverse, even as discussions on cultural appropriation and who can make whose culture’s food have begun to take shape. Asian Americans have also long been silenced or perceived as apolitical, so creating this platform was our “lane” in the activist sense.

Shirley: From our first moment of connecting in 2019, Diann, Anthony, and I have been talking about our respective and mutual interests and experiences in food and cooking—personal and professional (we each have worked in some capacity in restaurants/food), writing, and the political and cultural intersections of those subjects. We each love food deeply and find personal meaning and joy in cooking. Everything starts there. It’s a bit of a cliché to say this, but I do believe that important conversations often begin at the kitchen or dinner table. Our story is no different: we started talking about our experiences with/in food and our respective interests in food and writing over several lunches (a memorable one at Sai Jai Thai in San Francisco).

On Lunchbox Moments, I wanted to work on something that would, hopefully, be meaningful to readers, relevant to the moment, and also doable. We had real-life constraints of various kinds, but we also wanted to make this work. Speaking for myself, I wasn’t thinking about a platform; I’ve never been particularly quiet about where I stand on political issues. What I did want, though, was to do good work in line with my values, help create a platform for others to tell good stories, and raise money for communities affected deeply by the Covid-19 pandemic.

What was the most challenging part about putting the zine together? How did you address the challenge?

Diann: From a logistics angle, we conceptualized and executed the project entirely remotely. In fact, the first time we were all able to gather in person since meeting in 2019 was only recently. We staked ourselves to an ambitious publication date (about seven months from concept to execution). From an emotional angle, the increase of violence against Asian Americans came to a heartbreaking crescendo with the Atlanta and Indianapolis shootings, not to mention the media’s sudden reportage of violence against Asian elders and especially in the San Francisco Bay Area. We were editing the selected pieces during that time period, and the editorial process was both a cathartic way to process the communal grief but also simultaneously traumatizing. The challenge was keeping ourselves motivated, remotely, when sometimes I think all we wanted was to fall apart or hide underground when our communities were under attack, but we pressed on because we knew the work had to be done.

Shirley: We came together to work on this project because of what we observed during (and before) the pandemic—the negative rhetoric and physical violence directed at Asian Americans. As the pandemic went on, the relentless news coverage of what was happening affected each of us deeply. We were editors, yes, but we were also people observing and experiencing what was happening in the world around us and to our communities, processing the collective grief and also our own individual personal griefs, which were real and deep.

How did we deal with the challenge? I think the most critical thing was that we really trusted each other and held each other through it as colleagues/collaborators. We had weekly meetings to keep us on track, and at certain points, one of us would say, “Hey guys, I just can’t manage this right now.” And the others of us would say, and we meant it, “No problem, you take a little time away from the project. We’ll hold it and keep it going.”

How was Lunchbox Moments conceptualized? What inspired you most to create the zine?

Anthony: When we first thought about this theme, we learned from articles in NPR and Eater that challenged the value of stories about lunchbox moments. These articles argued that the traditional lunchbox moment narrative excluded many AAPI individuals who never have these moments and overemphasized feelings of shame. In response, we broadened our language in our call for submissions. It was inspiring to see the various pieces that came in and how people interpreted the lunchbox moments theme. We heard from writers and artists who had always been proud of their lunch, who felt their lunch hadn’t been Asian enough, and who shared about lunchbox moments in fields beyond food like language and familial relationships.

Diann: Yes, we wanted to shift focus from the stinky food narratives that have been so pervasive that lunchbox moments have become a trope. We sought out narratives that we found most interesting was how many people had lunchbox moments within the community or within themselves. On a personal note, I lost my grandmother and gave birth to my first child in the midst of our short, but ambitious publication process. For me, the zine became a sort of driving force tribute to both my grandmother and my child—of memories past and future.

Shirley: What inspired me the most at the very beginning was the opportunity to showcase stories featuring Asian American writers, to have some creative control over the project, and to do so in a way that was in service to the larger Asian American community. This was a remarkable opportunity to work with my really talented coeditors and friends, to work on compelling subject matter, and to uplift the work of our wonderful writers and artists. It was also an opportunity to learn about what it takes to bring something like this into being.

What do you hope that your readers take away from Lunchbox Moments?

Anthony: I hope people recognize the diversity in the stories told, especially in the range of emotions shared. These aren’t just stories about lunchbox moments focused on shame that elicit rage, guilt, or sadness. To me, this isn’t a collection of stories about Asian Americans being victims of discrimination. Instead, each piece complicates our definitions of being Asian American.

Diann: I hope readers come away with more questions than answers regarding Asian American identity. The Asian American identity has long been boxed in by the “model minority” myth and is not a monolith, and disparities abound between ethnicity, class, color, and generation. Even rereading the stories again today, there are different meanings I pick up every time.

Shirley: What Diann and Anthony said. And also, for some readers, I hope that they come away with a sense of recognition and connection to the stories told. I’ve just been asked to speak to a college-level class on Asian American women writers about Lunchbox Moments and feel so gratified to know that students are reading this work. I hope that readers can see the power of sharing their personal experiences—whatever they are and however they fit into or don’t fit into a particular trope around what it means to be Asian American. And honestly, I really hope that readers come away with a hunger for new food experiences as well as a recognition that meaningful stories about our lives can come in many forms, including about something as seemingly mundane as our everyday interactions with food.

How did you know that storytelling through and about food has power?

Anthony: Food is an important way for immigrants and their descendants to connect to their cultures. In the collection, I witness the different ways this connection is interpreted, lost, or reinforced, often across generations. I feel that many people can connect to this idea of food traditions changing over time. Also, since announcing the zine, I’ve spoken to many people, not just AAPI individuals, who have strong memories about school lunch and the cafeteria. A common theme has been being bullied for receiving free or reduced-price lunch. It seems like there is something formative in those childhood meals.

Diann: With the popularity of platforms like Instagram and Yelp, foodie culture relegates food for its consumptive value. There’s an adrenaline rush in waiting in line for three hours for the next hottest food trend, of taking so many photos the meal gets cold, and then getting your followers to obsess over the geotag location. In our stories, however, food is a character. Food is symbolic, food is catharsis. Food inspires all types of emotions.

Shirley: There are moments in our lives that we never forget—the big moments—the weddings, the births, the deaths, the loves, the trials and tribulations. And then there is the smell of freshly baked chocolate chip cookies. The sweetness of ripe summer strawberries encased in soft whipped cream. The pungent smell of savory salted fish and chicken fried rice. But the two—the big moments and the smaller moments—are not unique and separate. As Diann says so beautifully, food is a character, yes. Food and our interactions with it reveal things about ourselves as characters that are meaningful. This is especially true for some who grow up in families that are not particularly verbal or direct in communicating about emotions and feelings—except about food. When this is so, I think showcasing food in the storytelling can be particularly powerful.

Why did you choose to partner with San Francisco’s CCDC?

Anthony: To clarify, we are not partners with the organization. We just named them as our beneficiary. They operated two iterations of Feed + Fuel Chinatown over the last year and a half, which was a program that combined supporting Chinatown’s residents and its businesses, especially its restaurants. We wanted to respond to the xenophobia that has hurt Chinatown businesses since the start of Covid-19 (and before shutdowns in the U.S.).

Diann: People may not be aware of the racist, segregated history that allowed for the creation of Chinatown and laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Chinese were thereby limited in what occupations they could take, and cooking was one of them. Chinatown and Chinese people have long been synonymous for immigrant communities and Asians, so when [then-President Donald] Trump spouted vitriol like “Kung Flu” and “Chinese virus,” it undoubtedly felt like an invisible history was repeating itself. Yet that time period is not that long ago, as my parents were both born in Chinatown and would have benefitted from an organization like the CCDC if it existed back then. So our decision to donate funds to CCDC was a way of giving back to those historical immigrant roots.

Shirley: We actually put a lot of thought and research into it, knowing that whatever organization we chose needed to be one that the three of us each connected with and supported. Diann and I both grew up in San Francisco, with ties to Chinatown. Anthony grew up in the South Bay, with less of a personal connection to San Francisco Chinatown. We also conceived of the project as having a national focus; we were looking for diverse contributors, not just in terms of cultural identities, but also regional location. So we initially set out to find a beneficiary that contributed to the needs of immigrant restaurant workers, supported Asian American communities, and had a national focus. We looked at entities doing direct service and doing other kinds of more capacity building work. We didn’t want to default to a San Francisco Bay Area based organization just because we happened to be located here. We ended up choosing CCDC because of its long-standing work in San Francisco Chinatown and its tremendous work on the Feed + Fuel program, feeding low-income folks living in Chinatown single room occupancy hotels. We recognize that San Francisco Chinatown-based organizations have been at the forefront of advocacy on behalf of Chinese Americans and Asian Americans nationwide since the beginning of Asian immigration to America.

In what ways can readers support the Asian American community during the pandemic? After the pandemic?

Anthony: Over the last year, I was shocked to have discussions with individuals who never or rarely thought about discrimination against Asian Americans. I hope we can learn more about both the history/legacy of discrimination against AAPI communities and also the parts of these cultures that inspire pride and celebration.

Diann: During and after the pandemic, readers can support the community by patronizing Asian American businesses and following Asian American creators on social media. Of course, the issues are systemic and deeper than capitalism or social media algorithms. Readers can, as Anthony suggested, dig into the history/legacy of discrimination—read anything by Helen Zia or Ronald Takaki and watch the Asian Americans documentary on PBS.

Shirley: Good question. There are many ways in which readers can support the Asian American community during and after the pandemic, some of which Anthony and Diann have already touched on. I think reading about history and discrimination and patronizing Asian American owned businesses are important. I would also add a few more things: slow down and listen. The experiences of Asian Americans (if we can still use that term—a conversation for another time) are multiple and diverse, and we must make space to hear about them. Also: history is now. So when you go to read about the history of Asian Americans, remember to look for sources about what is happening now—and not just about shootings and violence perpetrated against us. Try reading Hyphen magazine, Asian American Writers Workshop’s The Margins. See what’s happening at sites like Asian Americans Advancing Justice—Asian Law Caucus and Asian Prisoner Support Committee. Stand up for people if you see them being bullied or harassed. I recommend the Hollaback Bystander Intervention training.

Have you experienced any lunchbox moments of your own as Asian Americans in a workplace or school setting?

Diann: I’ve experienced my own lunchbox moments from outside but particularly within the Asian American community—from the expectations of me being able to fold immaculately crimped dumplings or steam a perfectly tender whole fish. I never learned to use chopsticks the proper way, and I got called out recently about that—I retorted back to the person that, well, at least I knew how to eat. Even for someone who has cooked professionally, this idea/ideal of perfection while performing Asian identity is stifling, and cuts into complex memories of family, language, and diaspora. It’s something I’m still grappling with to this day.

Shirley: I have experienced lunchbox moments mostly in the workplace or private context from people who would never identify as racist in any way. They were microaggressions—for example, expectations that I would know something about a particular kind of frozen dumplings “because you’re Chinese, you should know” said with absolutely no irony. Another time, the person in charge of ordering a work lunch refused to even consider Chinese food “because it’s so greasy.” She clearly had never had beautiful, nongreasy, delicious Chinese food. I don’t know if this relates to lunchbox moments, but I definitely relate to Diann’s grappling with internal perfectionism and its relation to creation of food. Also, even the notion of perfection could be subject to greater scrutiny. What is perfection in light of differing experiences of what is authentic and real, both in terms of food and in terms of identity?

Will there be a follow-up publication?

Anthony: We are undecided at this time but thank everyone for their generous support.

Diann: (laughs) We had joked that maybe we could start a podcast themed around current events in food media. Stay tuned. In all seriousness, as Anthony had said, we are undecided at this time.

Shirley: Ha, Diann. I would just add that we are undecided, but you know, if someone chose to fund our working together and you know, perhaps help mentor us on the next publication, that might help move us in a certain direction.

Shirley Huey (she/her) is a Chinese-American writer, editor, consultant, daughter, sister, friend, collaborator, cook, music and theater lover, cat mom, and former civil rights attorney. She believes that place and race matter and that we can make the world a better place from wherever we are, right at this moment. Born and raised in San Francisco, Shirley’s writing can be found in such publications as Berkeleyside, Catapult, Panorama: The Journal of Intelligent Travel, The Universal Asian, and Endangered Species, Enduring Values, an anthology of San Francisco writers and artists of color. She has received fellowships from VONA, Kearny Street Workshop, SF Writers Grotto’s Rooted and Written, and Mesa Refuge, and is working on a memoir in essays about food, family, and social justice.

Diann Leo-Omine (she/her) is a culinary arts creative and writer rooted in San Francisco (Ramaytush Ohlone land) and the colorfully boisterous Toisanese diaspora. She now resides in the North Central Valley (Nisenan land), in between the ocean and the mountains. Her writing can be found in The Universal Asian and the Write Now SF anthology Essential Truths.

Anthony Shu’s (he/his) first experience in the culinary world came as a breakfast cook at a nonprofit summer program where the “kitchen” consisted of a Presto griddle set up outdoors. He graduated from Princeton University in 2016 and after a brief career in more professional kitchens, Anthony started working at Second Harvest of Silicon Valley and has been focused on client storytelling and multimedia production for the last few years. Also a freelance food writer, his work has been published in Eater SF and the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

Rachel Vinyard is an emerging author from Maryland and a publications intern at Yellow Arrow Publishing. She is working towards her Bachelor’s degree in English at Towson University and has been published in the literary magazine Grub Street. She was previously the fiction editor of Grub Street and hopes to continue editing in the future. Rachel is also a mental health advocate and aims to spread awareness of mental health issues through literature. You can find her on Twitter @RikkiTikkiSavvi and on Instagram @merridian.official.

*****

Thank you to Anthony, Diann, and Shirley for taking the time to thoughtfully answer Rachel’s questions. Please visit the Lunchbox Moments website to learn more about this initiative and purchase a PDF copy of the zine today!

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. Thank you for supporting independent publishing. Visit yellowarrowpublishing.com to learn more about submitting, volunteering, and donating.

Celebrating EMERGE: Coming Into View and Pandemic Stories

By Brenna Ebner

For this year’s Yellow Arrow Publishing value, board/staff picked EMERGE. It was a decision made to celebrate a new year after we all faced such uncertainty and turmoil throughout all of 2020. We felt the start of 2021 was especially important in this way and were grateful to be able to turn over a new leaf and welcome new times filled with opportunity and optimism. As we have progressed through the year, we have progressed as individuals and as a community. EMERGE spotlights the growth and change we have made be it from this past year or before.

With this yearly value, we chose to call upon Yellow Arrow staff and authors to spotlight their growth and change in our EMERGE zines. EMERGE: Pandemic Stories focuses on the ways in which our staff and authors have dealt with the uncertainty and fear from Covid-19 and the ways they have prospered from overcoming this daunting global challenge. Their experiences are ones many of us can relate to and ones that can open our eyes to the ways Covid-19 has impacted each of us differently as well. EMERGE: Coming Into View similarly focuses on change and growth many of us have had in facing the pandemic and racial unrest while also focusing on themes outside of this year. The stories included take place at many different times and touch on family, self-empowerment, and racial identity as well.

Both zines are now available through Yellow Arrow’s bookstore as a PDF (for a donation). And on our YouTube channel, we just released prerecorded videos of several EMERGE authors reading their incredible pieces. Please show your love and support for our authors.

To celebrate the release of both EMERGE zines, we are sharing Aressa V. Williams’ piece “Good Company” from EMERGE: Pandemic Stories. Aressa shares her experience in turning her time in quarantine into something productive and rejuvenating for herself. She delves into her passion of creative writing as a tool to help in her self-reflection and a way to find solace within herself. Her newfound practices of mindfulness, boundaries, and healing speak to the ways in which we are able to transform even when stuck at home. Aressa’s transformation during quarantine is inspiring and uplifting as it gives hope to each of us to be able to do the same kind of EMERGING even in the face of great setbacks and loss. EMERGE celebrates not only these recent transformations but many others as well. With our zines, we hope to encourage each of us to continue growing, changing, and EMERGING.

“Good Company” by Aressa V. Williams

Solitude during the pandemic gave me time for self-examination, a soul check. Like so many, I took freedom for granted. Before Covid, my retirement days were busy. Tutoring, shoe shopping, dining with friends, attending matinees, coming and going as I pleased. But since I love my peaceful, safe abode, I did not mind the national time-out at home. I created a rhythm and flow to make the best of my seclusion. In fact, the quarantine was an unexpected chance for reflection, meditation, and creative writing.

I thought about foolish mistakes made in the past. Dropping by coworkers’ homes without calling or being invited. Complaining to my supervisor’s boss without first talking to my supervisor. Hurting a close friend’s feelings. “What? Pregnant again!” Too many unfiltered comments, missteps, wrongdoing. Why didn’t I know better? I imagined going back in time to apologize to the victims of my venom. Scene by scene, I revisited people who were disrespected, offended. One by one, I asked for forgiveness. Visualizing warm hugs in sunlight, I hoped they felt my sincerity.

Daily meditations were a priority for frontline workers, our political leaders, Covid patients, and me. In addition to prayers, I experimented with “distant healing,”—sending energy and well-wishing to those in need far away. I managed to keep my gratitude journal up to date while evening news reported pandemic deaths, racial injustice, and political discord. When bad news and pessimistic friends overwhelmed me, I fasted from negativity. I did not answer the phone, nor check text or email messages, nor listen to the news. Instead, I read inspirational articles, listened to love songs, watched black-and-white movies, walked wearing my mask, and engaged in positive self-talk. The personal time-outs were rejuvenating.

And home was my writing retreat. I took advantage of several creative writing opportunities and several heartaches. Between drafting, revising, and editing four poems and one essay, I lost eight people. Three family members and a close friend died of fatal diseases; four classmates died of Covid. I was forced to reconsider thoughts about death. Old sayings like “we are only visitors here” and “tomorrow is not promised to you” did not comfort me. Consequently, journal writing became my grief therapy. Composing poems, obituaries, and letters to honor the lives of loved ones eased sadness. Family and friends (and I) were grateful.

All in all, my creative retreat proved fruitful as all writing submissions were published. More importantly, months of reflection, meditation, and journaling introduced me to a new role. A recluse with a purpose. Aloneness is good company.

Brenna Ebner is Yellow Arrow’s CNF Managing Editor. She previously interned with Mason Jar Press and was Editor-in-Chief of Grub Street volume 69 at Towson University. She also does freelance editing on the side and is slowly making her way through a CNF reading list.

Aressa V. Williams, a retired Washington, D.C. public school teacher and a retired assistant professor of English at Anne Arundel Community College, is also a teacher consultant, creative writing presenter, and poet. She is an active member of Pen in Hand, Poetry X Hunger, and Poetry Nation. Equally important, she accepted the new role as a Literary Leader for the Prince Georges County Arts and Humanities Council. In the sixth grade, the aspiring message-maker wrote her first book of poems to earn a Girl Scout badge for Creative Writing. Today, Aressa has three self-published books, Soft Shadows, The Penny Finder, and most recent Pancakes & Chocolate Milk. Her inspiring poems strike universal notes about family, friends, resilience, and hope. Aressa believes that poems are word snapshots of our experiences. Moreover, she defines poetry as word music. The word-weaver enjoys walking at School House Pond, journaling, and interpreting dreams. Other interests are reading short stories, posing poll questions, and sky-watching. A good day for Aressa includes morning meditation, afternoon tea, and if possible, a nap. The poetess is the proud mother of Aaron Coley and grateful grandmother of Aressa Coley.

*****

Every writer has a story to tell and every story is worth telling. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

Announcing EMERGE: Coming Into View and Pandemic Views

By Brenna Ebner

For this year’s Yellow Arrow Publishing value, board/staff picked EMERGE. It was a decision made to celebrate a new year after we all faced such uncertainty and turmoil throughout all of 2020. We felt the start of 2021 was especially important in this way and were grateful to be able to turn over a new leaf and welcome new times filled with opportunity and optimism. As we have progressed through the year, we have progressed as individuals and as a community. EMERGE spotlights the growth and change we have made be it from this past year or before.

With this yearly value, we chose to call upon Yellow Arrow staff and authors to spotlight their growth and change in our EMERGE zines. EMERGE: Pandemic Stories focuses on the ways in which our staff and authors have dealt with the uncertainty and fear from Covid-19 and the ways they have prospered from overcoming this daunting global challenge. Their experiences are ones many of us can relate to and ones that can open our eyes to the ways Covid-19 has impacted each of us differently as well. EMERGE: Coming Into View similarly focuses on change and growth many of us have had in facing the pandemic and racial unrest while also focusing on themes outside of this year. The stories included take place at many different times and touch on family, self-empowerment, and racial identity as well.

Both zines will be available through Yellow Arrow’s bookstore as a PDF (for a donation) on September 28. And on the same day on our YouTube channel, we will release videos of several EMERGE authors reading their incredible pieces. Please show your love and support for our authors. More information can be found on our events calendar.

As a sneak peek, we would like to share Nichola Ruddell’s piece “Emerge” from EMERGE: Coming Into View not only for the fitting title but because it perfectly encapsulates everything we have felt as a whole going through the uncertainty of the pandemic and in finding the courage to push on. Nichola emphasizes the importance of poetry as a way to cope, understand, and process the hardships we have faced during 2020 and the fear of what is to come next in 2021. But with the powerful tool of writing and a newfound sense of bravery, Nichola inspires us to follow in her lead and focus on the strengths we have gained through this experience and from our passions. EMERGE celebrates not only these recent transformations but many others as well. With our zines, we hope to encourage continued growth, change, and EMERGING.

“Emerge” by Nichola Ruddell

As I emerge from this year, I feel a certain hesitancy to move forward. The transition back to a life we once knew after a year punctuated by fear and loneliness, a year of panic and anxiety will be slow and fraught with hard decisions. Our round and ripe world full of possibilities is also a world deeply fractured, chaotic, and messy. The pandemic illuminated the world’s shadows and deep inequalities and injustices were brought to light. Many of us struggled to find a way to contribute, connect, and reconcile these inequities. Collectively, we confronted this pandemic yet each person has had a unique and important experience.

For most it was incredibly challenging. I found the ebbs and flows of life seemed to be quicker, louder, and sharper. There were flurries of fear and then periods of stagnation.

As a parent with school-aged children, my primary focus has been our children’s mental health and their safety. During the height of the pandemic, I often felt like I was out at sea without an anchor. The children had questions that my husband and I could not answer. They wanted to know when this would end and life felt fragile. Their innocence required us to stay strong, confident, and hopeful.

During this time, I wrote regularly using immediate and urgent poetry to integrate any experience that felt overwhelming, beautiful, or mundane. My father and I decided we would try and write a poem each day to each other over text message. It helped me stay connected and inspired me to write without constraint. “For me, poetry is a beautiful stone revealing the unearthed, holding the weight, and shining a light to experience.” As we enter the month of June, British Columbia is beginning to open up. This poem “Don’t Choose” draws on the mixed feelings that have arisen during this time:

We fly through this aching world

in moments of fire and stillness

We revel in magnificence

and then shelter in minutia

Fire

Stillness

Magnificence

Minutia

In this aching world

Don’t choose

This summer will be very different from last, and I know there will be residual fears and unknowns. I am worried that I have lost the ability to be with others and not fear getting sick. I worry that my children fear the same. Yet I also know that with time there is a settling of self and many opportunities to pause, reflect, and integrate this past year with myself and others. We know how to keep safe in our surroundings, school, and work, and we continue to learn how to live in this new way.

Our family continues to grow stronger as we navigate this time together, and I have witnessed such kindness and connection between friends and our community.

Poetry has carried me through the roughest of days and continues to strengthen my ability to reveal my truth and create meaning in our current world.

I’m not certain what the next few months will reveal, but I know that even as I continue to wrestle with hesitancy, fear, and uncertainty, I will push forward into this next phase with a renewed strength and deep gratitude.

Brenna Ebner is Yellow Arrow’s CNF Managing Editor and project lead for EMERGE. She previously interned with Mason Jar Press and was Editor-in-Chief of Grub Street volume 69 at Towson University. She also does freelance editing on the side and is slowly making her way through a CNF reading list.

Nichola Ruddell was born in Vancouver, British Columbia, and raised on Salt Spring Island. She attended university at the University of Victoria, receiving a degree in Child and Youth Care. She is also a Phoenix Rising Yoga Therapist. She enjoys writing poetry and is previously published in the online magazine Literary Mama. Her poem “Movement in the Cinnabar Valley” was published in Yellow Arrow Journal, Home Vol. V, No. 2, and she recently became an associate member of the League of Canadian Poets. After living in many places with her family, she has made a home in Nanaimo, British Columbia with her husband and two young children.

*****

Every writer has a story to tell and every story is worth telling. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

Taking Moments to Listen: A Conversation with Ute Carson

“I’m never someone who sends out a mission to my readers, but I want them to stop a moment when they read and maybe say: what do the words mean? Could that be applied to something in my life?”

Ute Carson, German-born, now Austin, Texas resident, is the author of Yellow Arrow Publishing’s next chapbook, Listen. The desire she has for her readers to pause and engage with her words is evident within the lines of the 44 included poems. Listen’s imagery forces readers to stop and sit with her words for a few moments before continuing to evaluate the book’s themes: engaging with nature and loved ones and reflecting on one’s past experiences and their subsequent formative effects on the ensuing years. Ute’s words convey to her readers her enchantment with the world around us during every stage of our existence.

A writer from youth, Ute has published two novels, a novella, a volume of stories, four collections of poetry, and numerous essays here and abroad. Her poetry was twice nominated for the Pushcart Award. Yellow Arrow is privileged to publish Listen, now available for PRESALE (click here for wholesale prices) and released October 12, 2021. You can find out more about Ute at utecarson.com. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram for Friday sneak peeks into Listen from this week until October 8. Recently Editorial Associate Siobhan McKenna took some time to get to know Ute and the significance of Listen.

As a young child in Germany during World War II, Ute was bombarded by the tragedies of the world: her father died in the war before she was born, her mother’s second husband was also killed, her two uncles perished in the brutal Stalingrad winter, and she, her mother, and grandmothers were forced to flee their home—losing everything—as the Russians invaded. Yet, Ute remembers, “In spite of a very dramatic childhood, I was embedded in this incredible love. Even when I saw the most terrible things. I saw for the first time wounded soldiers—crying, dying. And that left a deep impression on me. But at the same time, I was always protected by these females around me, so I was able to choose that same influence that warms and protects you all through my life. And I have tried to impart that to my children and my children’s children.”

We carry the house of childhood within us,

and spying through its translucent walls,

we keep life at a distance or embrace it.

(The House of Childhood)

As the women in her family worked together to shelter Ute from the dangerous times, they told stories, and Ute began to understand the power of writing. “My maternal grandmother, my father’s mother, and my mother were all steeped in German poetry, stories, and I absorbed all that.” In addition to the songs and tales that she was “fed,” Ute’s writing was influenced by an elementary school teacher who “always ended each class with a story” and helped her publish her first story in the German magazine, Der Tierfreund (Friend of Animals). From that moment on, Ute says she has never stopped writing.

We all have been warmed by a fire we did not build.

Parents set a fire

that sends out sparks to dispel darkness,

and lights the way for the young into the world.

(Flames Rising)

In Listen, Ute weaves a poignant narrative of what it means to be engaged with the world by drawing on her childhood influences, educational background, and experiences as a friend, lover, and grandparent. Many of her poems emphasize understanding one’s place in the life span and the collective conflicts we face as humans. This is only fitting as Ute herself studied various psychological theories and was a clinical hypnotist at a trauma center in Austin for many years. Being able to write about universal struggles is an important aspect of Ute’s poem as she often changes perspective or leaves the speaker deliberately ambiguous. In the poem “She Still Lives Here,” Ute writes as a husband mourning the loss of his wife. “I changed perspectives because I try to generalize. I don’t always bring it back to me.” She continues to say that writing poetry “is not just telling about your experience, which is very valuable—you start with your experience—but your experience has to be formed. It’s not enough to just put it out there. What you do as a writer and a poet is to transform [the experience] into something that is universally human and that’s how it appeals to my readers (not just to my family) who can then relate my personal experience to their own. I am a critic of people who just write about their experience and do not attempt to empathize to the human condition.”

How do we venture into the lives of others

and still remain true to ourselves?

[. . .]

We build barriers, high and solid,

wire fences between properties,

[. . .]

My favorites are the ones made of rope

that I can climb over or crawl under.

(Self and Others)

In addition, many of Ute’s poems use her current role as a grandparent to view the world. In “Breaking Away,” Ute writes that grandparents are the “hub in the wheel of life” as they “relieve busy parents” and “indulge the young.” Ute believes that grandparenthood is easier than parenthood and says that she loved being a parent, but between teaching, writing, getting a graduate degree, and having three girls that she was “always torn in different directions.” Now, when one of her grandchildren “bursts through the door everything else can be wiped away. Even the ailments, which you know when you are 80 years old, they are there, and you forget for a moment because a child beams and throws [themselves] into your arms.” She says it is not simply that you have more time, but also more “psychic energy” to spend on your grandchildren because “you are no longer preoccupied with your development” and the questions of, “Who am I as a writer? Who am I as a parent? Who am I as a wife?” Because “as a grandparent, you have pretty much shed that search for the self and know who you are. And that is very comforting because you can then convey that to your grandchildren.”

How difficult it is to picture our parents as young lovers,

or the bearded homeless man as a smooth-skinned baby.

It takes a leap of imagination

to peer through the fog of time

and see each stage in life

linked from first to last.

(Snapshot in Time)

But despite loving the view from grandparenthood, Ute also writes of the limits that she has encountered with aging. In “Relinquishment” she laments no longer being able to wear her favorite heels and in “The New Normal” attempts to race her grandson only to find that she immediately falls. When asked about this experience, she says, “I had it in my mind that I had been a runner and that I could still run, and I fell absolutely flat and that’s the flexibility we need to learn in old age. That yes, you still know how it was when you were able to run, but you can’t do that anymore . . . there are final limits.”

The wind of mortality

sweeps through the woods,

stripping away leaves

and downing limbs.

Sap turns to bleeding tears.

(Bleeding Trees)

Throughout the collection, Ute blends childhood memories with her insight that comes with aging, which begs the question: What does it mean to live a full life? To this, Ute answers that she loves being able to care for her animals and garden. She snuggles with her cat, grooms her horses, and tells her roses, “I’m sorry, but you need a haircut.” But, above all, she says that a full life to her has meant her experiences with her mate. “My husband—who has been at my side for so long. We have had things that we have had to struggle with in terms of ailments and all kinds, but we do life together still and we still very much enjoy what we’ve always enjoyed. My husband had an incredibly busy professional life. And, not that we weren’t connected during that time, but there is a different connection now. Now the time together that we spend [is not between] him flying off to the next meeting or to colleagues. It’s a kind of circle that you come around to appreciate your partner—whoever it is . . . I don’t mean you have to have one [singular], but the partner that comes around as we age is important. Someone that you can fold wash with and do other everyday tasks even when you’re old.” She adds, “[My husband and I] still fight over politics. We still have our own things that we do. But it is still valuable time spent together, [we ask] how do we want to structure our last years together? And that includes the family, the animals, the garden, the reading, all that, but a primary focus on the partnership.”

Life stories are recorded in the crevices of my brain

and emotions bounce back from hollows in my body.

I am filled with the echoes of my loved ones.

(Echoes)

Ute interweaves among her themes of youth, love, and aging images of verdant forests, abundant flowers, and other nature scenes that give color and scents to her sentiments. The significance of the abundant nature imagery is echoed by her decisions on the title and the cover art (designed by Yellow Arrow Creative Director, Alexa Laharty). When asked, Ute explains that Listen came from a question when she was giving a reading for her last book, Gypsy Spirit. “One of the listeners said, ‘I read your book, and I am slow, is that a detriment?’ And I said, ‘No, on the contrary, if you’re attentive, if you’re reflective, if you listen, much more will come with a second reading.’ It’s ok to be slow and to reread and maybe pause at an image. Or reflect: What did you mean by this word when you could have used another one?” Furthermore, Ute says she has often used listening to nature as a way to heal.

“Go, and put your ear to the tree, which is [on] the cover [of the chapbook] and listen to what that tree has to tell you. What energy does it send to you? We have done it with the grandchildren very often. When I couldn’t solve [a problem] even with my hypnosis, I would say let’s go outside and you put your arms around the tree, and just listen very carefully. Because the tree maybe tells you something. Maybe a stomachache, and [my grandchildren] often would come back in and say, ‘It’s gone.’” Ute further expands that with nature we have a reciprocal relationship: “Many of my nature references are allegories. . . . In the story about my grandson hugging a tree when he had a stomachache, I tried to show that everything around us is alive and has its own energy. Our grandson could bring his discomfort to the tree and in turn receive solace. The book cover image has a different focus—listening instead of hugging. [Depicted on the cover is] a woman (or girl) [leaning] her ear against a tree. There is a symbiotic connection. She might feel the ‘Earth move under my feet’ as Carol King sings and the sun might touch her face or she might be listening to birds chirping, the wind whispering.” Ute emphasizes that art is symbolic of being able to pause and pay attention to the natural world around us.

. . . when light and warmth return with the dawn,

butterflies flutter about.

Nature thrives in abundance.

(Magical Greenery)

And it is not only with the title and cover art that Ute had very specific intentions. Everything she has done to have Listen come alive has been deliberate—even her decision to publish with Yellow Arrow. Ute expresses that when she was first introduced to Yellow Arrow, she saw the logo and immediately realized that it was the symbol associated with the Camino de Santiago that helps guide “the wanderers and seekers” along the way. Ute and her husband completed the pilgrimage in the late 1980s and soon discovered that Yellow Arrow’s founder, Gwen Van Velsor, had also taken a pilgrimage there. “So when I saw the yellow arrows coming from that old tradition it connected with me that the chapbook is also a pilgrimage. The poems are a pilgrimage from childhood to the dying and we stop along the way.” She continued to say that not only did Yellow Arrow’s connection to the Camino de Santiago solidify her decision to publish with us, but also its mission to emphasize women. “I love to comment on that because there are not that many journals that are geared toward women.” Ute further says that she has often heard of two main theories that women will follow about art: a theory by Virginia Wolfe and one from Anaïs Nin. “According to Wolfe, all art is gender-free. But I have chosen the other tradition: Nin. And [Nin] believes that art overlaps—men’s and women’s art overlaps, but men and women have a slightly different perspective on things. And, she said that women write with their blood. You dip your pen in your blood and you write with it. So, if you are of that tradition—as I am—you have a different perspective on the [Yellow Arrow Journal] and why it’s just for women. I want women to be aware of that tradition. And you do have to come in your mind to make a decision about which one you want to follow.”

By exchanging stories,

We can reach understanding.

(Talking and Listening)

*****

Every writer has a story to tell and every story is worth telling. Thank you, Ute and Siobhan, for such an insightful conversation and to Siobhan for sharing it. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts.

A Delicate Art Form: CNF Interviews

By Siobhan McKenna, written July 2021

from the creative nonfiction summer 2021 series

In the artistic realm, structure often surprisingly enables creativity. Within poetry many iconic poems follow specific meters, famous painters learned the basics before venturing into abstract styles. And conducting an interview for a creative nonfiction piece is no different. The interview is a delicate balance between applying a clear form to your conversation while also allowing yourself, as the interviewer, to flow with remarkable or unforeseen information. Below, we dive into a few guidelines to conduct a successful and thoughtful interview.

1. Research

For an interview to go smoothly, a writer sets up the conversation for success through their preparation. Before the interview, a writer must be familiar with the background of their subject and understand the basic context surrounding the interview by conducting research on their subject. Within the Yellow Arrow community, research often looks like reading brief bios or the material of an upcoming chapbook to be published by one of our writers or poets.

2. Prepare Questions

When researching, it is helpful to take note of significant themes or intriguing sections and then form questions that you think would lead to an interesting conversation. Preparing questions ahead of the conversation is vital because they help outline how you would like your conversation to go. Still, if a conversation moves in a surprising way, it is beneficial to comment and ask follow-up questions rather than remaining attached to your script. In other words, be genuinely curious.

3. Be Human

Curiosity, as well as empathy, can transform a rigid Q&A session into an earnest and illuminating conversation. As the interviewer, responding with an emotional response—if moved—can shift the conversation to a more intimate place that may give rise to meaningful or surprising answers. While originally known for his outlandish questions and crude comments, Howard Stern evolved his interviewing style over the years to incorporate more empathy and to draw on personal experience. In a 2015 interview with Stephen Colbert, Stern asked Colbert about whether part of the reason that he became a comedian is that he felt compelled to “cheer up” his mother after his father and two brothers died in a plane crash (2). While hesitant at first, Colbert eventually comments, “There’s no doubt that I do what I do because I wanted to make [my mother] happy—no doubt” and follows up with a question for Stern:

COLBERT: How [did] you know to ask that question?”

STERN: Because I spent many years cheering up your mother, as well. I didn’t want to tell you this.

(LAUGHTER)

STERN: No, no. What happened—my mother lost her mother when she was nine. And my mother became very depressed when her sister died, and I spent a lot of years trying to cheer up my mother. And I became quite proficient at making her laugh and doing impressions and doing impressions of all the people in her neighborhood.

In the conversation that follows, Stern and Colbert discuss how their experiences with trying to make their mothers happy shaped their relationship with women and their careers. If not for vulnerability on both sides of the conversation, this insightful glance into how some people may process and transform tragedy as young children and their relationship to their parents could have been glossed over.

4. Build Rapport

Nevertheless, deeper conversations like the one between Colbert and Stern depend on the rapport that you have built with the interviewee. According to Terri Gross, “Tell me about yourself” are the only four words that you need to know in order to conduct an interview (1). Gross, the host of NPR’s Fresh Air, has been conducting interviews on the segment since the 1980s and insists that opening with a broad introduction allows the subject to begin telling their story without the interviewer posing any assumptions. Being broad can allow the interviewee to define how they view themselves and their work and lead to creating a safe space where they will feel not feel judged by their answers, but rather better understood.

5. Transcribe

Once finished, there are several ways to transcribe your discussion into a creative nonfiction piece. One method can be to write a brief introduction of your subject and conversation followed by a direct transcript, which alone can be very poignant. Another common method is to paraphrase your conversation and use direct quotes to emphasize certain points in conjunction with your own observations when conducting the interview. Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah’s interview of Missy Elliot does an excellent job of showcasing how to include biographical information, her questions, and her reflections of her subject as she sat on set for one of Missy’s photoshoots (4):

Across the street from the photo studio, the Chelsea Piers are turning themselves over to the night. And Missy’s publicist and team are in a hurry to make sure I’m not taking up too much of her time, but Missy herself doesn’t seem rushed to go anywhere yet. If anything, she seems deliberate. She sips through a straw from a cup of fresh-squeezed juice, and then she holds the cup with both hands. Her baseball cap is cocked to the side, and her two-inch nails are painted iridescent blue. Her legs are open but locked at the ankle. She looks in command—even more so because she is smiling.

I want to know more about her absences from the spotlight. What is it like to reenter a world where Twitter can determine who becomes president, where music can feel like it was created to last for exactly for one minute and then disappear into the ether?

Yeah, it is a brave new world, she agrees. But she isn’t despondent. Not at all.

“One thing I won’t do is compromise.” She takes another sip of juice and thinks for a moment. “I will never do something based on what everybody else is telling me to do. . . . I’ve been through so many stumbling blocks to build a legacy, so I wouldn’t want to do something just to fit in. Because I never fit in. So. . . .”

I wait for her to finish her sentence, but she doesn’t. Her smile just grows into a laugh, a shy one, and then she shrugs. As if to say, take it or leave it, love me or leave me.

6. Final Notes

At Yellow Arrow, we love that as a style of creative nonfiction, the interview allows the writer to create a unique piece that not only tells us about the subject but can delve into deeper truths about our society through the conversation. We often use the interview when promoting new books to help illuminate the book’s themes and to gain a glimpse into the thoughts of the writer before releasing their work. Take a glance back at an interview with Patti Ross from February 2021, whose chapbook, St. Paul Street Provocations, was just published by Yellow Arrow. And make sure to read next week’s blog from an interview I did with Ute Carson (find her bio here!), whose chapbook, Listen, will be published by Yellow Arrow Publishing in October 2021. Presale begins next week!

Delve into Some Other Interview Styles:

Profile: Rachael Kaadzi Ghansah: Her Eyes Were Watching the Stars: How Missy Elliot Became an Icon, https://www.elle.com/culture/celebrities/a44891/missy-elliott-june-2017-elle-cover-story/

Radio Show Transcript: Terri Gross. ‘Fresh Air’ Favorites: Howard Stern, https://www.npr.org/2019/12/31/790859106/fresh-air-favorites-howard-stern

Traditional Q&A: Jordan Kisner. tUnE-yArDs Made a Pop Album About White Guilt—And It’s Fun as Hell, https://www.gq.com/story/tune-yards-made-a-pop-album-about-white-guilt-and-its-fun-as-hell

(1) Kerr, Jolie. “How to Talk to People, According to Terry Gross.” The New York Times. 17 Nov. 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/17/style/self-care/terry-gross-conversation-advice.html

(2) Gross, Terri. “‘Fresh Air’ Favorites: Howard Stern.” NPR. 31 Dec. 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/12/31/790859106/fresh-air-favorites-howard-stern

(3) Friedman, Ann. “The Art of the Interview.” Columbia Journalism Review. 30 May 2013. https://archives.cjr.org/realtalk/the_art_of_the_interview.php

(4) Kaadzi Ghansah, Rachael. “Her Eyes Were Watching the Stars: How Missy Elliot Became an Icon” Elle. 15 May 2017. https://www.elle.com/culture/celebrities/a44891/missy-elliott-june-2017-elle-cover-story/

Siobhan McKenna was born and raised in the suburbs of Philadelphia. She stumbled upon Yellow Arrow while living in Baltimore and has loved every minute of working as an editorial associate. Siobhan is currently working as a travel ICU nurse in Seattle and is loving biking and hiking throughout the Pacific Northwest. She holds a bachelor’s degree in writing and biology from Loyola University Maryland and an MSN from Johns Hopkins University. You can follow her on Instagram @sio_han.

******

Thank you to everyone who followed along with our creative nonfiction summer 2021 series. Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. Thank you for supporting independent publishing.

Yellow Arrow Journal Submissions are Now Open!

Yellow Arrow Publishing is excited to announce that submissions for our next issue of Yellow Arrow Journal, Vol. VI, No. 2 (fall 2021) is open September 1–30 addressing the topic of “belonging-ness,” exploring what it means to belong or un-belong, our nearness or distance (intimacy or alienation) from others and ourselves.

This issue’s theme will be:

Anfractuous:

full of windings and intricate turnings

things that twist and turn but do not break

How has your “belonging-ness” been shaped by your own personal life journey? Have you taken any sharp unpredictable turns, or has it been a slower accumulation or a shedding?

Is it necessary to “belong” to be happy? How has your sense of who you are been a process of “un-belonging”?

How have your circumstances (the land you live in or don’t live in/your family history) or your conscious choices (your chosen family/career/passions) tempered or shaped your understanding of your own belonging?

Yellow Arrow Journal is looking for creative nonfiction, poetry, and cover art submissions by writers/artists that identify as women, on the theme of Anfractuous. Submissions can be in any language as long as an English translation accompanies it. For more information regarding journal submission guidelines, please visit yellowarrowpublishing.com/submissions. Please read our guidelines carefully before submitting. To learn more about our editorial views and how important your voice is in your story, read About the Journal. This issue will be released in November 2021.

We would also like to welcome this issue’s guest editor: Keshni Naicker Washington. Keshni considers her creative endeavors a means of lighting signal fires for others. Born and raised in an apartheid segregated neighborhood in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa, she now also calls Washington, D.C. home. And after nine years here has finally gotten used to Orion being the right way up in the night sky. Her stories are influenced by her evolving definition of home and the tides of political and social change that move us all. She is an alumnus of VONA and TIN HOUSE writing workshops. Connect with her keshniwashington.com and on Instagram @knwauthor. You can also learn more about Keshni through her Vol. V, No. 3 (Re)Formation piece “Alien” and her Yellow Arrow Journal .W.o.W. #20.

The journal is just one of many ways that Yellow Arrow Publishing works to support and inspire women through publication and access to the literary arts. Since its founding in 2016, Yellow Arrow has worked tirelessly to make an impact on the local and global community by advocating for writers that identify as women. Yellow Arrow proudly represents the voices of women from around the globe. Creating diversity in the literary world and providing a safe space are deeply important. Every writer has a story to tell, every story is worth telling.

You can be a part of this mission and amazing experience by submitting to Yellow Arrow, joining our virtual poetry workshop, volunteering, and/or donating today. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram to learn more about future publishing and workshop opportunities. Publications are available at our bookstore and through most distributors.

*****

Yellow Arrow Publishing is a nonprofit supporting women writers through publication and access to the literary arts. To learn more about publishing, volunteering, or donating, visit yellowarrowpublishing.com.

Getting Personal with Personal Narratives

By Katherine Chung, written July 2021

from the creative nonfiction summer 2021 series

We often forget how important events and celebrations can be. Sometimes we forget to write things down or take a photo of an event. Oftentimes, we do not realize how important something, or someone, is until we lose them. While this last sentence describes my life perfectly, it also sounds like something that we may hear from our parents or mentors.

Personal narratives are like short chapters of an individual’s complete memoir. This specific style of writing allows people to recall a memory and share a personal experience through writing. Such short stories can be about a specific experience and can be intense and hard to comprehend. And wonderful.

Typically, authors write in the first person when they are describing personal experiences. And by writing from their unique point of view, authors can use their five senses to vividly describe a scenario to their audience. This descriptive language also allows the audience to step into the authors’ shoes. Authors are able to set a rich setting so that the audience knows when and where (and why) the personal narrative took place. Some authors like to add quotes and photos to their narratives to make their stories feel more personal. And sometimes some authors use their photos as cover images while others may put a collage of photos at the end of the story. Each author who writes a personal narrative can be as specific or general as wanted to tell a story.

Most personal narratives are written in prose and are 1–5 pages long. They do not need to be exceptionally long since most events written about occur in a quick instance, such as a few hours.

The most common technique used for personal narrative writing is storytelling, which allows authors to retell a story that has made them who they are today or allowed them to overcome a life obstacle. It may even be difficult for an author to recall a memory from the past to write about, but the storytelling element allows an author to add a fictional aspect to a personal story. For example, some authors choose to change a person’s name for the sake of privacy. In another example, an event could be boring so fictional additions might spice things up.